По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

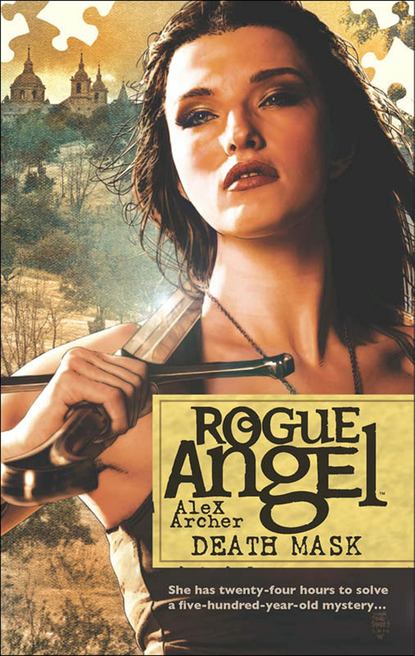

Death Mask

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Of course, sir. Is your interest in the Inquisition?” The driver had struck on the connection straightaway, but then no doubt everyone who visited the place had that particular interest.

“One of many,” he said. “Do you know it well?”

“I worked there as a tour guide during my studies. Unsurprisingly, people only ever wanted to hear the goriest details of tortures.”

Roux smiled. “Human nature, my friend. And, you must admit, there’s plenty to keep them entertained.”

“Oh, yes, but it was always more fun to make up something particularly awful, just to watch them squirm.” He laughed.

Roux liked the man. Sometimes there was too much truth in the world. A guide having a little bit of fun at the expense of a few tourists wasn’t that big a crime...all things considered.

“You’re more than welcome to come inside and revive your fledgling career as a tour guide,” he offered.

“It’s your dime, boss,” the man said. “Doesn’t matter to me if I’m kicking back in the car waiting for you to come back, or if I’m giving you the grand tour of the ruins. Costs the same for you. But are you sure you want me making stuff up?” He grinned in the rearview mirror as he pulled into traffic.

The journey was short, the private landing strip only a few minutes outside of town. The driver didn’t take any risks, waiting patiently for the lights to change before indicating and turning right, going against the flow. The entrance to what remained of the Castillo de San Jorge lay next to the market in the center of Seville, though the remains themselves were buried beneath the “new” market, close to the river Guadalquivir. New was a relative term. There’d been a market on the spot for over a century. Roux could remember what it had been like before. Sometimes his longevity weighed heavily on him. He could look at the ever-changing world and realize just how little of it was actually permanent, and no matter how much it changed, none of those changes lasted all that long.

It was going to be damp in the ruins, moist and clammy, especially where they butted up against the riverbed. There was no guarantee he’d even be able to get that far. He couldn’t remember what the Castillo de San Jorge had been like in the late 1800s when he’d last been there. There certainly hadn’t been a visitors’ center, though, or tour guides to answer his questions.

Mateo dropped him at the entrance, then went to park the car.

By the time he returned, Roux had worked his way through the selection of brochures without finding what he needed.

The driver slipped his phone back into his jacket pocket as he approached. Roux nodded, assuming the man had taken a few minutes to chat with his employers or the significant other in his life. In the past fifty years or so, the world had changed so much he didn’t even automatically think “woman in his life” when he looked at a handsome guy like the driver.

“Everything okay, boss?” Mateo asked. “You look...troubled.”

“I’m reading about how the trials actually took place in the Town Hall.”

“The Ayuntamiento? That’s right. But this is where the first auto-da-fé took place, making it very much the birthplace of the Inquisition. The first executions happened in Seville. Those poor souls who fell foul of the Inquisition were burned alive on a platform designed just for the purpose.”

Roux sighed deeply. “There’s no end to the ingenuity of men who want to make others suffer.”

“Spoken like a man who knows his stuff,” Mateo said. “Do you want to know what the real irony is?”

“Go on, amaze me,” said Roux, expecting to hear one of those little lies the driver had used to spice up his guided tours.

“The guy who designed the burning tables they called the quemadero was a Jew. He became a victim of the Inquisition himself.”

“So his ingenuity bought him no favors with the men in power.”

“None.”

It was no different from Joan of Arc’s France, Roux knew. There, the executioner might have had mercy on the “witch” and snapped her neck before she burned. It was barbaric and brutal, and the horrors he’d seen over the centuries still lived on inside his head.

They moved through the room, toward a display that showed a reproduction of a painting by Goya along with sketches of suspects wearing pointed hats and tabards bearing a cross that marked them as being under investigation by the Inquisition. Roux had seen the original many times, and not only on the walls of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando in Madrid, where it hung. He had spent almost a year in the artist’s company after he fled to Paris. The last time they talked had been only days before Goya suffered his fatal stroke. It brought back so many memories, some of which he would much rather forget.

“You think it was really like that?” Mateo asked.

“Not at the beginning,” Roux said. “But by the end, certainly.” He spoke with more certainty than the driver could have expected. But then, the man could never have guessed the old man he was talking to had witnessed many of the Inquisition’s horrors firsthand.

“There are some more of his drawings here in Seville,” Mateo said. “Some of them are studies that may have led to this painting.”

“Are there?” Roux had thought the artist had destroyed everything related to his dark pieces. This was news to him. But did it matter? Was this the important thing he’d been hoping to find? A few sketches by a lost friend?

“They are in the Museum of Fine Arts. Fifteen minutes’ walk from here, not even half that in the car.”

“Then what are we waiting for?”

“They aren’t on display—they’re only brought out for special exhibitions.”

“There are always ways and means,” Roux said.

He suddenly had a hunch and was curious to see what of his old friend’s art had survived. He remembered Goya’s fascination with the darkest days of his country. The man was a scholar with a passion for learning and a habit of hiding those things he had discovered in his art—especially in the sketches that formed the foundations of the finished paintings. There was no telling what he might have hidden on those charcoals. Roux hadn’t planned on this detour, but the few minutes it would add to the search could prove invaluable in the long run.

Roux didn’t waste his time calling some petty bureaucrat in the museum. He cut to the chase, speed-dialing one of the movers and shakers in the country. The woman was on the board of a number of museums and art galleries and could pull strings quickly. She was also an ex-lover, which made the first sixty seconds or so of the conversation a little awkward. It had been more than thirty years since they’d spoken, and although she sounded much the same, she couldn’t be the young woman she had been, even if he was exactly the same man he was that last time he’d lain down beside her. The phone line was like the dark, though. It hid the truth of the years between them.

She promised the pictures would be waiting for him when he arrived. He promised to come visit her soon. One of them was lying and they both knew it.

The traffic made the journey slower than Mateo had suggested, but only by a few minutes, and it gave the curator time to set up a private room with the sketches displayed for Roux’s viewing. The curator, a short, balding man, met them at the door as they arrived, a hand held out in welcome as if they were old friends.

“Welcome,” he said, ushering Roux inside. “I was given to understand you only have a limited amount of time, and with the very short notice, well, the space we’ve been able to make available for viewing...isn’t optimal. The lighting, et cetera... I hope you understand.”

“Of course,” Roux said, waving away the apologies. “I’m sorry it was such short notice and appreciate your efforts to accommodate a demanding old man.” He smiled wryly.

“Please, please,” the little man said, “let’s just forgive each other, then. This way, gentlemen.” He offered a mildly disapproving glance in Mateo’s direction as the driver climbed out of the car to follow them.

“It might be better if you wait with the car, Mateo,” Roux said, deciding he’d rather not have a witness. There was a chance money might well need to change hands, if the curator was holding out on anything, and a man was always more susceptible to a bribe if he wasn’t being watched.

Once they were inside the room it was clear why the curator had been reluctant to have the extra body inside. The private viewing room was barely larger than a broom cupboard—a particularly small one, at that—and was obviously set up for restoration work rather than viewing. A woman Goya would have dearly loved to have painted waited for them inside the room.

“Our collection of Goya drawings is really quite remarkable, the pride of our humble little museum,” the woman said. “We were incredibly fortunate to have these willed to us in a patron’s estate many years ago. They are by far the most precious treasure we have in our care.” She waved an open hand toward a folio on a workbench that had been cleared. “Please.” She slipped on a pair of cotton gloves before she opened it. “Just let me know when you are ready, and I’ll turn them over.”

Roux was momentarily disappointed he wasn’t going to be able to touch the drawings himself, but then they were the property of the nation, and she had no idea Roux’s own face could be hidden away inside one of them, just another one of the artist’s little jokes.

She opened the folder to reveal the first of the pictures.

It was a study of a man’s face beneath a pointed hat.

The second was the face of a monk.

The third was of a row of officials sitting in judgment.

None of them were significantly different from the final pictures he’d seen in Milan.

But as the woman revealed the fourth picture, Roux’s breath caught.

The sketch was of a mask, or rather, a face wearing a mask.