По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

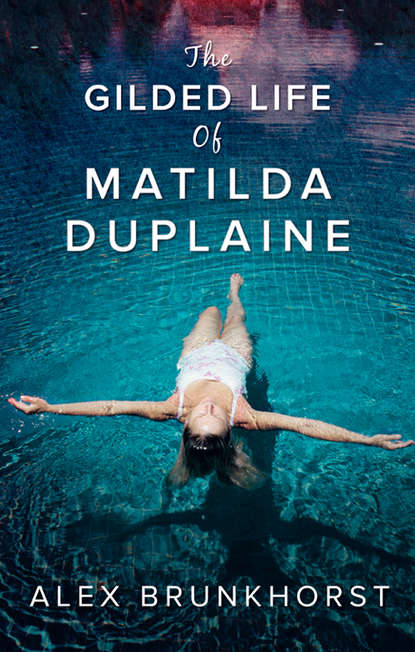

The Gilded Life Of Matilda Duplaine

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

As a guy, it was my job to find an open window when a girl closed a door. I found a slight crack here—in her unsure inflection, her avoidance of eye contact, her choice of syntax.

So I climbed through the proverbial window. Five rackets wrapped in cellophane sat on a bench beside the court. I unwrapped one, took off my shoes and walked to the other side of the net.

I had played tennis in high school and, despite some rustiness, would have considered myself a good player. I rocketed in a pretty decent first serve, but before I had time to admire it she had nailed a backhand return that hit the place where the baseline met the sideline.

“Wow, good shot.”

“Thank you,” she said.

My next serve was a nasty topspin down the middle, and once again her return skidded off the baseline.

Twenty minutes later the first set was over. I had won a mere five points.

I walked up to the net, and she followed suit. She put out her hand proudly to shake mine.

“I’m now 1–0,” she said, glowing.

“1–0?”

“Yes, one win and zero losses. Still undefeated for life.”

“You’re meaning to tell me this is the first match you’ve ever played?”

“Correct.”

“Your entire life?”

“The whole of it. I only practice,” she said, her victory still covering her face.

“How often?”

“Three hours a day.” She paused, contemplating what was to come next. “Do you like cookies?” she asked as she headed toward the tennis pavilion.

* * *

The tennis pavilion was more elaborate than most houses. Ivy crept up the walls and partially hid glass casement windows. Reclaimed wood covered everything. I had the feeling this wood had been to France and China and back—all before the eighteenth century. A seventy-five-inch television screened a muted Gregory Peck film. An old stone mantel stood six feet high, covering a brightly burning fireplace below, surely crafted before the advent of central heating systems. Silver pitchers of lemonade and water sat beside crystal glasses. Six varieties of cookies were symmetrically lined up on trays, and towels floated in steaming hot water. Every provision was taken care of.

“Lemonade?” the girl asked.

“Sure. Thanks.”

She poured me a glass of lemonade to the brim and then put on a short satiny jacket that must have been the companion piece to her dress because the frills matched. Beads of sweat rested in the nape of her neck like seed pearls. She didn’t wipe them off.

A bowl of pineapple sat in a crystal bowl. The fruit was diced into equally cubed pieces, small and dimpled like playing dice. The girl plucked out a piece of pineapple with a fork, holding it up so the fruit dazzled under the soft light in the pavilion.

“Can I interest you in a piece of pineapple?” she asked.

“Yes, please. Pineapple’s my favorite fruit.”

“Mine, too,” she exclaimed with great enthusiasm, as if she’d just discovered that we had the same birthday or the same mother.

She slowly placed the fork in my mouth, and I tasted a few drops of its delicious juice before the entire cube of fruit went in. It was sweet, perfectly ripe. I pictured the farmer in Hawaii leaning over fields of pineapples, picking just this one, for just this girl.

She stared at me long after the pineapple had made its way down my throat. I was accustomed to being the observer, but in this case I was clearly the observed. Surprisingly, it felt nice.

The girl sat down and motioned me toward an antique leather chair beside hers. On the wall between us hung a modern painting of a lawn full of sprinklers. It was an image I recognized from art history books as a David Hockney. I assumed the painting was an original.

“I can’t believe you beat me 6–0. I didn’t give a good first impression,” I said. “Do you know what a 6–0 set is called?” I asked.

“No.”

“A bagel. Because the zero is round like a bagel.”

She smiled grandly, and I noticed she had great teeth. They were a bit crooked, but in a good way.

“I’m Thomas, by the way.” I made a long-overdue introduction. “I should have probably said that earlier, right?”

She didn’t introduce herself in turn. She took a long sip of lemonade with mint leaves.

“You should really think about playing in some tournaments. I think you’d do really well,” I said.

“You do?” she asked, leaning closer.

“Yes. You seem the competitive type.”

“Is that a compliment?”

“I like girls with chops, so yes.”

“With chops?”

“Yeah, with chops.”

“I don’t know what that means, but I hope it’s a good thing. And I’ll think about it—the tournaments, I mean. I don’t think I’d be very good at losing. Are you good at losing?”

“No one is,” I said, taking a sip of my lemonade. “I’m surprised your coach doesn’t encourage you to play matches.”

She stared into the distance, where David’s grand white house loomed. We could only see its six chimneys—but it was there, in the background, bigger than us.

“My coach would like me to, but it’s complicated.”

She looked toward her yard, as if a missing puzzle piece lay somewhere in that rolling acreage. But wait, was this even her yard? I was so mesmerized that I hadn’t considered this question. Even in a city obsessed with dating young she was too young to be David’s lover. And if she were, wouldn’t she have been at the political event?

The girl focused her gaze on me—first on my hair, then my forehead, then my nose and then my mouth. She moved lower, studying my body obviously and examining the barrel chest of my torso and the calves that I had spent my boyhood covering up because they were too brawny for the rest of me. She eventually settled on my jaw.

“You have such a nice jaw,” she said sweetly. “It’s a man’s jaw.”

I smiled and found myself blushing.