По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

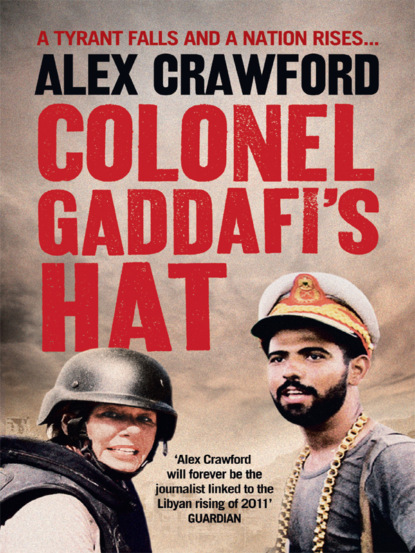

Colonel Gaddafi’s Hat

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Hmmm, let me think about it,’ I say, playing for time.

Sometimes I don’t even have the chance to say goodbye. They might be at school, on a play-date, or it could be I leave in the middle of the night to catch a flight or make a connection. If I can, I try to leave little notes hidden around their rooms. They don’t say much. Maybe ‘I love you’ or ‘Remember when you are reading this, I am thinking of you and missing you loads.’ Sometimes – much to their irritation – the notes will have more functional messages, such as, ‘Have you brushed your teeth yet? I will know if you haven’t!’ and ‘Remember to do all your homework, even the reading for twenty minutes a night bit.’ I’m not sure it helps fill the yawning gap of an absent mother, but they tell me they enjoy trying to find the notes under their pillows, hidden in their school books, tucked away in their underwear drawers.

My eldest, Nat, who is 15, gives the outward appearance of being the most stoic about it all. He’ll just anxiously ask how long I’ll be away and where I am going. He’s not happy in Dubai, where we’re living now. He doesn’t much like the new school. He doesn’t much like the students. He misses India (where we were previously posted) and all his friends there. He’s still sore at us for taking him away from his old life and he’s constantly asking to go back. Oh dear Nat, no, my love, there’s no going back. My heart is hurting for him. I loved India too and I desperately want him to be happy. But the job is here now. In Dubai, in the Gulf. And the Middle East and North Africa are bubbling with discontent. And not just Nat’s either.

The dynamics of the family change when one of us is absent. I notice, when one of them has a sleepover elsewhere, the noise levels dip, there are different family allegiances, different sparring matches. When Mum disappears for weeks it must alter considerably. Frankie is the second eldest (just 13) but far more mature than all of us put together. She used to be terribly upset when I disappeared for work before, now she becomes very angry. And she doesn’t seem to get used to it either. She just gets angrier.

‘Mum, you really have to sort out your priorities,’ she tells me. ‘Why do you have to go? Can’t someone else do it? Why you? Just tell your news desk you have children, Mum. Don’t they realize that? You know what, Mum, when I grow up I am going to do a job where I actually see my children.’ Wow, the volleys are coming in thick and fast. Frankie gives me the hardest time out of all the children but also bombards me with affectionate text messages while I am away. But she has one final warning: ‘And you better not miss my birthday, Mum.’ It’s coming up in less than three weeks. Yet another deadline to meet. Oh, my gosh, I’d forgotten all about that. That’s going to be tight.

Maddy, at 11 years old, is the least outwardly perturbed of the three girls and probably the most interested in news events and what’s going on in the world. She records her own little news diaries on her mobile phone and always signs them off: ‘This is Maddy Edmondson for Sky News.’ She has an audience of one – Maddy Edmondson – and occasionally Maddy Edmondson’s mother. She has her own Twitter account too – long before her mother was encouraged by her office to get one. I think she had three followers – her two sisters and her mum. She’s more a Facebook girl. But Facebook doesn’t replace a mum who is away working. She doesn’t like me going away either. They all – Nat apart – cry when I leave, and as soon as the door shuts they start counting down the days until I am back.

And then there’s Richard – a hugely successful and decorated racing and sports journalist who is now largely responsible for keeping the Crawford–Edmondson household afloat. Sometimes even close friends ponder: ‘And what’s old Rick doing these days?’ What? You mean apart from looking after the four children, doing the homework, the cooking, the ironing and the school drop-offs? Well, yes, in between he’s also trying to do some freelance writing and keep a foothold in the business he loves while his wife is off racing round the world. Yeah, not up to much really.

Richard gave up his job on the Independent newspaper after more than twenty years so I could become a foreign correspondent, which involved us all moving to India so I could take up the post of Asia correspondent at the end of 2005. It was a lot harder than either of us imagined. For a start, I’m sure you know, the world is still very sexist, one which remains largely divided on gender lines. And it’s emphasized particularly when you are an expat living abroad. Richard will quite often be the only man doing the daily drop-offs at the international school gates, the only man at the parent ‘get-to-know-you’ lunches, the only man solely organizing his children’s birthday parties, the only man at the school coffee mornings. It is hard for him and I have no doubt it is also very lonely.

There’s also a crushing loss of status which many women will be all too familiar with after having children and stepping off the career ladder. I wouldn’t say Richard is used to it by now. Does anyone ever get used to it? My former Foreign Editor, Adrian Wells, used to say he should be canonized. ‘How does he put up with you? How does he put up with it? How on earth does he do it?’ are the common questions. And if Richard is viewed as a saint by some, I often feel the opposite about my own status.

Most of the time I feel I am failing – failing as a mother, failing as a wife, failing as a foreign correspondent – because I can’t give any of my roles the time I want to. A foreign correspondent’s job requires 150 per cent commitment. I have waited so long to be a foreign correspondent based abroad and came to it that much later in life. I feel I have a lot of catching up to do. It’s a 24/7 job and to do it well you have to put in so much time and effort. The necessary skills of being a mother of four often seem to involve having the organizational and diplomatic qualities of a CEO cum banker cum chef cum sergeant major. I constantly feel torn between all of my roles and feel like I am not succeeding at any of them.

Now I’m the main breadwinner and, for all the pain caused by constantly leaving the family, the work has to be worth it. I can’t afford to do a bad job. It has to be good. Well, more than good. Otherwise why put everyone through all of this? I love the job, the places it takes me to, the people I get to meet, the stories just waiting to be uncovered. To be honest, I love the thrill and the adventure – so much so, it often feels terribly selfish. I don’t enjoy being shot at. It’s not the danger I love. Often I am terrified. Rather it’s the opportunity of going to corners of the world I wouldn’t get to if it wasn’t for my job. It’s the chance to make a difference somewhere to someone. Along with many foreign correspondents I realize how damn lucky I am to be doing this job and frankly I don’t want to screw it up. I want them – my family – to be proud of me. I want them to feel like it’s worth it. For all our sakes, I must try to do my best in Libya.

This particular departure coincides with a visit by the in-laws – or it is about to. This will ease the pain for all considerably, particularly Richard. His parents, June and Bill, have arrived in the region for a holiday. They are going on a mini cruise which was booked months ago and – unbeknown to them at the time of booking – seems to take in all the Middle East revolution hotspots – Bahrain, Oman, the Gulf of Aden. Half the itinerary has been adjusted, with many of the hotspots crossed off owing to ‘uprisings’. So now it’s just the pirates they have to watch out for. After the cruise, they will stay at our home in Dubai for the rest of their break. Good. The children will be distracted by loving grandparents. Richard will be distracted by being run off his feet as the host.

Right now, though, I have got to pack. The goodbyes are always horrendous and, to be honest, I want them over as soon as possible. They’re just too hurtful for everyone.

Wednesday, 2 March

Martin and I fly from Dubai to Tunis and meet Tim Miller, Sky’s Deputy Foreign Editor. He is a hugely popular figure in the newsroom – easy-going, sensible, always pleasant to deal with. ‘Bonjour, mes amis,’ he says with a broad smile. ‘Allez, Libya!’ We’re pleased to see him. We’re all pleased to be on the trail of the story. For now, all we can see is the future.

The plan is that the three of us will enter the country legitimately but try to shake off Gaddafi’s ‘minders’ as soon as possible. Their remit is to ensure the ‘right’ Gaddafi version of events is broadcast. Our remit is to try to report on what is really going on inside Libya.

At least that’s the plan. The three of us relocate to a small café in the airport where we have the first of many croque-monsieurs waiting for the Tunis Air check-in desk to open. But when it does, the answer is a firm ‘Non!’

We are still waiting for the official letters from Tripoli cordially inviting our attendance and, as far as the airline is concerned, they do not exist. We beg, we plead, we rant with the elderly Tunis Air official, who is Libyan. We get letters faxed and emailed from Sky and show him our journalist press passes. Non, non and non again.

He asks if I can talk Arabic. I say: ‘Kafah halak’ (‘How are you?’) Somehow he recognizes I’m not a professor of the language. ‘How can you go into Libya if you don’t speak Arabic?’ He’s smiling a smile which indicates he’s not smiling much inside. I’m thinking, can you please just let us on the plane? What difference does it make to you? But he won’t be persuaded. In fact I think he’s enjoying our discomfort and our pleading. ‘I am so sorry, ma’am.’ He doesn’t look sorry at all to me. I think he’s a Gaddafi loyalist. He doesn’t want to make this easy for us. We don’t give up until the plane actually takes off.

Then it is time for Plan B. Tim has heard Air Afrique is letting people on without visas. That’s the good news. The bad news is the planes are leaving from Paris. We get the next plane to France. We book a hotel near to the airport, and by now we’re all becoming very twitchy about our complete lack of success in getting into Libya. We’re actually moving further away.

Still, optimism never dies. We have to hold on to that. I ask the foreign desk in London whether our colleagues in Tripoli need us to bring anything out for them. Lisa Holland has been reporting from the capital ‘under the restrictions of the Libyan government’, helped by producer Lorna Ward. We’re given a huge long list of items to bring out which includes coffee, tea bags, energy bars, sun cream, snacks and odour-eaters (no one owns up to asking for these). Tim gets up really early to rush round a supermarket close to the airport to fill a rucksack full of these various ‘essentials’. He rings up at one point as Martin and I are checking out of the airport hotel to ask for the French word for ‘odour-eaters’. Oddly, neither of us knows. Then we all set off for the airport.

We get as far as the check-in desk and, again, an airline official stops us. No visa? Hmmm. But she is a Libyan who has lived and worked in Paris for years now and is much more sympathetic. She has the personal number of one of the Gaddafi officials in Tripoli and rings him up in front of us. Somehow our names are on a list and she agrees to let us on. Hurdle one crossed.

It’s a short flight to Tripoli – only a few hours – and we are bursting with anticipation and suppressed excitement. What will it be like? How will we be treated? Will we get through the airport security OK?

When we land we are immediately segregated from the other passengers, the ones who all look like Libyans and have Libyan passports. We’re taken to a small room where there is already a European crew. They say they have been waiting for hours. We sit down. Within a very short time, the other crew is led away. They have their permissions to enter the country.

The BBC’s Wyre Davies is on our flight and he joins us in the room. There is a large picture of Colonel Gaddafi in the corner and I get Tim to take a picture of me with it. It’s the closest I ever get to the leader. So we sit and wait and wait and wait. All of us are tired already and we use the time to sleep. There’s plenty of time.

Wyre is told he has his visa within half an hour, but we are there for another three and a half hours. Finally we are allowed through immigration. As we walk out we see Wyre. He’s still here. He hasn’t been able to get any transport and he joins us. The airport is very busy. There are people milling around everywhere trying to get flights out. Many governments are evacuating their nationals out of Libya and those people who haven’t got help from their government are still trying to leave. Even though it’s dark and already night-time, it’s still pleasant temperature-wise – around the early thirties – typical Mediterranean weather, very balmy. We’re on the coast of North Africa but somehow it feels undeniably Arabic here, with a number of women wearing the hijab (Muslim headscarf). We walk out of the airport, following a Libyan official who says he will take us to the media hotel. We’re led onto a government bus and notice – even through the darkness – there are lots of people waiting outside the airport’s front entrance. We’re told not to film and none of us wants to do anything to irritate the official who has just let us into the country. So we don’t.

It feels tense. Everyone seems tense – the workers, the would-be flyers, the newly arrived, the armed guards who are standing both inside and outside the airport. Everyone seems edgy. Several towns in eastern Libya have already erupted in fighting – Tobruk and Benghazi are the two most notable. It began on 17 February, just over two weeks ago, when a general call for uprising was answered in several towns. It is the date the Libyans are calling the start of their revolution. They’ve seen their neighbours in Egypt (to the east) and Tunisia (to the west) rise up and defeat their dictators. Now it’s their turn. The fighting has already spread to Tripoli, with heavy gunfire heard in the capital and reports that the airport itself was taken by the rebels in the last week of February. Several planeloads of African mercenaries from neighbouring Sudan, Chad, Algeria and Niger have been seen being flown into Tripoli to help the Colonel fight his own people. Already there have been some defections from the Colonel’s own military: he needs to find other soldiers to help him stay in power.

The People’s Hall in Tripoli (banned to the actual people), which was the meeting place of the Libyan General People’s Congress, has been set on fire about a week before our arrival. Several police stations have been set alight, as well as the Justice Ministry in the capital.

We’ve seen pictures uploaded onto YouTube of Libyans burning the Green Book in Tobruk. This is Gaddafi’s book of ‘rules’ and ideas – his political and economic philosophy for Libya. It is compulsory reading for every Libyan, a sort of Libyan answer to Chairman Mao’s Little Red Book. It is both hated and scorned. In it, the Brother Leader, as the Colonel has renamed himself, teaches that the wage system should be abolished, that people should earn just what they need to and no more, that they should not own more than one house, that private enterprise is ‘exploitation’ and should be abolished. For the past twenty years, Libyans have told me, Gaddafi’s state machinery has even attempted to restrict access to private bank accounts so the regime can draw on those funds for government projects. He has set up People’s Supermarkets where prices are controlled. He says often that he wants to ban money and schools. As the American commentator Michael J. Totten put it, he ‘treats his country, communist-style, like a mad scientist’s laboratory’.

Despite some liberalization over the past couple of decades, there is huge discontent and many of the educated and wealthy Libyans have long fled abroad to neighbouring Egypt or farther afield to Britain and America. Now there are large street protests, the Brother Leader has responded with bizarre and eccentric speeches on state television, threatening to slaughter protesters and promising the death penalty for numerous crimes. In one speech he addresses his discontented nation from underneath an umbrella. ‘We will fight to every last man, woman and bullet,’ he says.

We were hoping to see here in the capital some of the seething discontent of forty-two years of built-up repression. We know it’s happening; finally Libyans are saying, ‘No more!’ But this seems to be contained in the east – in Benghazi and Tobruk. The fighting in Tripoli seems to have been quashed so far, with forces loyal to Gaddafi tightening their grip here. Certainly there’s no obvious sign of rebellion right now, not here anyway. I had expected more evidence of fighting somehow, but there’s none. Mind you, it’s dark. I half wonder whether that’s why we have been held in the airport for so long – to ensure we can’t see very much on the journey to our accommodation. And if that is the case, it has worked. The streets seem clean and quiet from what we can make out on the way to the hotel.

The bus journey is swift. The Rixos Hotel, our destination, is already full to overflowing, not just with journalists but also with Gaddafi officials and minders. Lorna has said there is no room for Martin and me, so we say we’ll go to stay at the Corinthia Hotel. This is the second media hotel, selected for us by the regime, but it’s some distance away and virtually unoccupied. Many journalists feel the place to be is the Rixos, as the news conferences are held there and any information to be gleaned from the Libyan authorities is probably going to come from this location. Martin and I are fine with being away from the media pack. We prefer it that way.

We get off the bus at the Rixos only to say a brief hello and goodbye to our colleagues. We’re famished, even more so when we notice that the hotel is serving the most wonderful five-star buffet. I look at Tim’s rucksack laden with snacks, tea bags and the vital odour-eaters and think, why did we bring all of that?

Martin and I guzzle down a quick meal. Lorna and Lisa have spent the day driving around Tripoli with Saif al-Islam Gaddafi (the Colonel’s second son but considered his heir apparent). They are very pleased with their journalistic coup. Lorna tells us: ‘You know, I’m almost beginning to believe them [the regime]. He got a very good reception out on the streets whenever we stopped.’ It sounds like quite a story and they have done well to persuade Gaddafi’s son to be filmed and interviewed in this way. It gives us all an insight into just how deluded and controlling the regime is. But this is a country where Saif and his father have outlawed all political opposition, where there is no freedom of speech or media, where people ‘disappear’ and are routinely tortured during interrogation or as a punishment.

I am extremely doubtful that Saif is really that popular and conclude – as all the journalists at the Rixos have already worked out – that this regime is bent on attempting to manipulate journalists and, for that matter, politicians too.

The hotel is extremely comfy and the food excellent. You wouldn’t find much better in many other cities around the world. It’s far superior to the fare offered at our Paris airport hotel the night before. It’s all very cleverly aimed at making the recipients feel well looked after and catered for. It is, unfortunately, a necessary evil for the journalistic fraternity to stay here. It’s the only way to get any access at all to the regime. I am certain it must take an especially strong type of person to remain untainted or unaffected by the twenty-four-hour-a-day brainwashing which must be going on around here. But many of the journalists present are the most senior from all the international channels around the world. If they can’t remain immune, then no one can.

Martin and I are desperate not to fall into the regime’s clutches in the first place. By staying at the Rixos we might find out how the mind of the regime operates (but our colleagues are doing that already). We want to find out for ourselves what ordinary Libyan people are thinking and what life is like for those outside these walls. We’re not going to be able to do that if we are escorted by Gaddafi minders, that’s for sure. Martin and I quickly adjourn to the Corinthia. We don’t want to be spotted by too many of the minders who are also staying at the Rixos. Tim will stay with the Sky team in the Rixos and we arrange to meet him first thing the next morning to work out a plan.

The Corinthia is a large, five-star hotel with two huge sky-scraping towers set just a little back from the Mediterranean coast. It has three impressive arches contained under a giant one at its entrance and looks incredibly plush – perhaps even more so than the Rixos. We step into a large, open-plan lobby with gold or gold-coloured furnishings and decoration everywhere. There are gold-coloured pillars, gold-coloured walls, wood floors with a sort of dark-gold sheen about them and a gold-coloured dome where the reception is. Set to the left of the reception is an odd-looking large silver bowl with water pouring out of it down some ornamental steps. Plush indeed, but there’s a big difference from the Rixos. The Corinthia seems to be deserted, with only about six guests in it – and they are all journalists. We see them sitting round a table the next morning. We go over to say hello. One of them is Richard Spencer from the Daily Telegraph, who is also based in Dubai but with whom I have spoken only on the telephone until now. There’s a guy from the Guardian and Anita McNaught from Al Jazeera. They are all very friendly and they give us a quick briefing about how difficult it is to get out without the minders. But occasionally they have managed to escape, mainly because they are away from the main media gang in the Rixos. I exchange telephone numbers with them and say we will try to keep in touch.

We go over to the Rixos and walk into the breakfast room, which is packed with journalists from around the world. Bill Neely from ITN comes up and says hello, friendly as ever. He is a fierce competitor but that doesn’t stop him from being approachable and good company. Then Paul Danahar, the BBC’s Middle East Bureau Chief, greets us. ‘They’re trying to get everyone to go to Sirte,’ he says. ‘They’re expecting trouble in Tripoli after Friday prayers today, so they’re doing their best to get as many of us out of the capital as possible.’ It’s generous information from a rival given to the new guys in town. There are different rules among competitors in a hostile environment, and he is being very helpful.

We have travelled light, carrying just two rucksacks with ‘day’ equipment. We’ve been told there’s a trip somewhere – by helicopter maybe, or by bus – and so we are just taking what we need for a day’s filming. After breakfast the journalists are causing a bit of a rumpus outside the front of the hotel. The minders are trying to persuade them to board a bus and no one much wants to go. There’s a row developing. Martin starts filming as a few of the journalists – led by Paul Danahar – start remonstrating with the officials, primarily Moussa Ibrahim, who is the Gaddafi regime’s spokesperson at the Rixos.

Ibrahim has a body language which reeks of hostility. He has prematurely thinning hair and a fairly stout figure which is clothed in the European ‘uniform’ of open-necked shirt and jacket. He is also staying at the Rixos – a fellow ‘prisoner’ – and we’ve seen him earlier having breakfast with his young German wife and very young child. He speaks impeccable English, having studied in Britain at Exeter University and afterwards taken a PhD at Royal Holloway College, London. He’s a very well-educated and adept arguer of the Gaddafi point of view. Right now he is walking in large circles in the hotel car park, trying to avoid answering Paul’s rather persistent points about leaving the hotel. Ibrahim is insisting he cannot let any of us out because our presence could trigger violence among what he calls the ‘affiliates of Al Qaeda’ who are on the streets outside. In the confusion, Bill Neely and his crew make a break for the hotel car park’s gate, which has armed men guarding it. The three of us just happen to be watching this all unfold. Yep, good idea, Bill, I think. We follow in their wake. We manage to get out before the guards are alerted and try to stop any more of us. Most of the other journalists are prevented from leaving.

Outside the Rixos is strange, uncharted territory for the foreign journalists. Few have been able to leave the five-star luxury of the hotel without a government chaperone. The regime has been insisting Tripoli is a city packed with Gaddafi supporters, any number of whom could turn us in or report us to the authorities, not necessarily out of loyalty but maybe out of fear. We’re not expecting to meet many friends out here.

Now some of us are outside the confines of the Rixos and out of the control of minders. We have escaped their gilded cage. We run straight away into a traffic roundabout which seems fairly busy with cars. There don’t seem to be many, if any, people walking around here. It is a built-up area and I can’t see much above the walls which have been erected around what look like residential properties next to the hotel. It’s just an intersection with about three or four roads leading off the circle and we’re all anxious to get as far away as possible from the Rixos as quickly as possible before the minders come out and find us.

Bill tries to jump into a taxi but the driver refuses to take him and his team. We head off in another direction, leaving them behind, and flag down a man who has his family in the car. The three of us cram ourselves in, apologizing and thanking him in equal measure. He has a Gaddafi poster on the front of his dashboard.

We ask if he can take us to Tjoura, where we have heard there has been some protesting by anti-regime people the evening before. He raises his eyebrows. ‘No, no, it’s dangerous. Too dangerous.’ OK, then maybe just to catch a taxi? He drops us off a few streets away and we manage to find a taxi. The man in control of the wheels appears to be the most grumpy cab driver in all of Libya but, crucially, he agrees to take us to Tjoura. Tim has photocopied a piece of paper written in Arabic which has been given to him by the Sky team in the Rixos. It is a letter-headed document from the regime saying we are journalists and should be looked after as we are travelling with the government’s permission and are accompanied by a Libyan representative (minder). This will be our get-out-of-jail card many times over.

We pass army tanks positioned at the entrance to Tjoura, a city on the south-east flank of Tripoli. But they don’t stop us. Tjoura is important to us for two reasons: it is the site of a nuclear research facility (Gaddafi has long harboured ambitions to build a nuclear weapon) and it is home to a considerable body of the Opposition, known to be the most anti-Gaddafi district in Tripoli. We are expecting there will be a large turnout today after Friday prayers to express this discontent once again. But it’s very quiet. Too quiet. The streets are empty. There are some smouldering piles of ash outside the mosque, but, even though it’s Friday and the time for midday prayers, the doors are shut and there’s no one around. We circle for a while but the taxi driver is not comfortable being here and so we head off towards the port.

In this vast country – the fourth largest in Africa – most of its 1.76 million square kilometres of land mass is consumed by the Sahara desert. Libya is around seven times larger than the UK but has only a tenth of the population and not a single permanent waterway throughout the country. The significance of Tripoli’s port is therefore huge. But, instead of the trading which is its hallmark, there we see thousands of migrant workers all waiting to be rescued from Libya. Some are from Côte d’Ivoire, which itself is suffering violent upheaval. But to them even Côte d’Ivoire seems preferable to Tripoli. These foreign workers are castigated by the Libyan revolutionaries, who think they may be Gaddafi mercenaries, while also being victimized by the indigenous population, who resent them for taking their jobs (there is 30 per cent unemployment). We film and interview many of them. Our grumpy taxi driver is anxious to go. He wants to get to the mosque, or anywhere else for that matter. What he doesn’t want to do is hang around for some foreign television crew. For a start, what he is doing will be viewed very dimly by the authorities and he runs the risk of jail or torture or worse. We pay him and he leaves, relieved.

Another man approaches us offering to take his place. He is rotund and middle-aged, with greasy hair, and looks decidedly untrustworthy. ‘Come, I will take you. Where do you want to go?’ he says. He’s seen our interaction with the grumpy cabbie and heard me talking to Martin. ‘Christ, what are we going to do now?’ or something along those lines. I hesitate. There’s something I just don’t like about the man. I can’t put my finger on it and it may well be unfounded but here I don’t want to give anyone the benefit of the doubt. I thank him and move away.

Another gentleman, in his late sixties, is also watching us. He says in an aside to me that the rotund, persistent man begging to be our driver is an undercover Gaddafi agent. I notice he is weaving in and out of the crowd but never going very far away from us. I have no idea whether he is telling me the truth or not but I instantly like the cut of this older, more calmly reassuring man. My instincts tell me he is OK and right now I have nothing else but instinct to guide me. There appear to be very few taxis and certainly none here. We are outside of the official set-up at the Rixos so we are very much on our own. Our office in London can’t help us either. It’s not like you can call up a minicab company or flag down a black cab.

Martin likes this man too, and I reckon if Martin and I think the same of someone it’s usually the right impression. ‘Will you drive us?’ I ask him. ‘We need help.’ It’s his turn to hesitate, but only very fractionally, and it’s immediately more reassuring still. He’s not doing this for the cash or because he’s the real Gaddafi agent. ‘Yes, yes,’ he says. We ask to go to Green Square. (This is one of Tripoli’s most notable landmarks, originally called Piazza Italia, or Italy Square, when constructed by the country’s colonial rulers. Then, during the Libyan monarchy, it became Independence Square, only to be renamed Green Square by Gaddafi, to reflect the political philosophy set out in his Green Book.) The elderly gent is a lovely man, very kind and constantly saying: ‘No problem, no problem. Everything good.’