По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

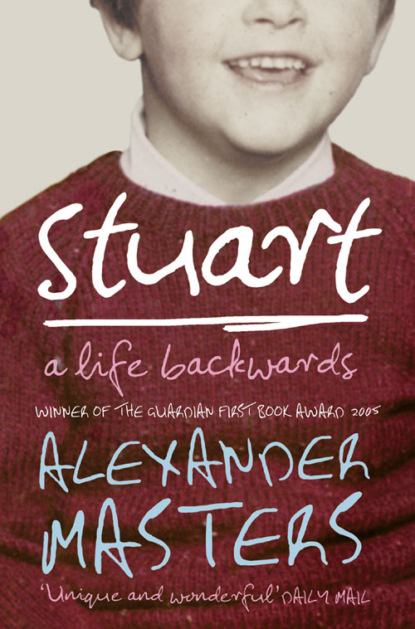

Stuart: A Life Backwards

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Stuart stood as he was talking. The chairwoman demanded it, and it appeared to cause him a little trouble to find his balance. He was about five foot six, bow-legged and anaemic. His hands he kept shoved in his jacket pockets like a man on the sidelines during a cold football match. He raised his voice for a few words when people at the back called out ‘Louder!’ ‘Speak up!’ then forgot himself and lapsed back into his regular murmur. But he would not stop talking. It was as though, having tasted at last what lack of diffidence was like, he was determined not to lose a single second of the pleasure.

‘Don’t expect the visits to go well, neither. See, because visits is only two hours every two weeks, when you’re a prisoner you build yourself up to such a pitch that when the visit comes it can’t go right. It’s not –’ directing himself at John’s wife – ‘that he don’t love you, it’s just that visits is all what you live for when you’re inside.’

‘Because if most men are true,’ he observed a moment later, ‘when they go back to their cells that’s when you know the loneliness. You can’t take it. You know the loss.’

And about the stone throwing, Stuart was adamant. ‘I understand the old dear there is feeling rageous, but prison is all about having privileges and taking them away. If you break the judge’s windows it’s Ruth and John what will suffer.’

‘How can they suffer more?’ an indignant man called out. ‘They’ve taken away their freedom and their dignity, what else is left?’

‘Their wages,’ replied Stuart.

A silence.

Then a bemused female voice from the other side of the room: ‘Prisoners get wages?’

3 (#ulink_9863f491-65df-5b80-b667-e1408f9fe8fb)

In the top drawer of Stuart’s large office desk are his legal drugs.

‘Yeah, feel free,’ he calls out from the kitchen, where he’s dumped the sarnie plates into the sink among the tea mugs and is battling with a six-pack of Stella.

I hold up a grey plastic tube. All the substances he takes appear to cause him problems.

‘Chlorpromazine. Cabbages you. It’s also called Largactil. Heard of it? No? The liquid cosh? Well, they gave it me a lot in the kids’ homes. Used to put me in a wheelchair in them days.’

‘Why do you take it at all?’ I wonder and place the tube back in his collection.

‘Nah – it’s just another anti-psychotic. The side effects are that it leaves a nasty taste in your mouth.’

Stuart reels off the names of his medications like a classics scholar. ‘Ophenidrine. A mate of mine what was looking on the Internet said he found Saddam Hussein used it for tactical military weapons. Zopiclone, what calms you; I’ve also been on drugs like Melarill, what are banned now, amitriptyline, painkiller, which gives you muscle spasms. Mad, in’it? At the minute I’m only on diazepam, which is Valium. It’s a well-known fact that alcohol and diazepam don’t mix, and they know I drink.’

‘They’ is shorthand for doctors, social workers, drug advisers and policemen, although in this case it is balanced against one doctor in particular whom he is convinced is out to ignore his interests. One of the things that intrigues me about Stuart is his categorisation of his enemies. The biggest foe is ‘the System’, the amorphous body of government-funded institutions that has chased him about like a bad rain cloud ever since he was twelve years old. All homeless people hate the System, even though many of its organisations – housing benefit, social security, the rough sleepers unit, dozens of charities – have been set up especially to make their lives easier. To Stuart these supportive bodies prove the essential duplicity of the System. What the person with a house might consider to be an admirable carrot-and-stick approach to making the homeless return to ‘mainstream’ society (the encouragement of welfare payments, back-to-work schemes, subsidised housing, backed up, for those who don’t cooperate, by the threat of the police and prison time) is looked at quite differently by Stuart. It is an approach that patronises you at one end and swipes you raw at the other. For many homeless, the reason they’ve ended up on the streets is precisely because this carrot-and-stick tactic has, in their case, got into a jumble. The government network of organisations that offers them dole cheques, a free health service and endless numbers of worried social workers, also puts them into a home with rampant paedophiles (unwittingly, maybe, but what does that signify when you’re fourteen years old with ‘a grown man’s dick down your throat’?) and then beats them up under the guise of ‘tough love’ in quasi-military youth detention centres whenever they do something wrong themselves.

The System is to Stuart a bit like the Market is to economists: unpredictable, unreliable, ruthless, operating in a haze of sanctimonious self-justification, and almost human.

The closest Stuart gets to giving the System a face is through the doctors, drug advisers, housing support officers and outreach workers with whom he deals directly. Although he is generally friendly to this little army of helpers, he respects almost none of them. When they are good, he talks about them as possible friends; when they are disappointing (which is frequently, because they are, after all, just people), they become another piece of evidence against the System.

Even one or two of the police he likes now and then.

At the moment Stuart is banging on about doctors. ‘Last Monday, my sister and me girlfriend were really worried because I’d gone doolally. Lost it. But my GP refused to even speak to them. They went up to him and said, “Look we’re really concerned about his safety. He’s got something tied round his neck, I’m not sure what it is, and he’s got knives all over the bed.” But he refused to see me. I thought that was really fucking rude!’

Recently, I asked Linda Bendall, one of the homelessness workers who helped Stuart when he was sleeping outside, ‘Why Stuart? Why did he make it off the streets when so many others have tried and failed?’

‘He is one of the rare ones. When I first met him he was completely, totally beaten up, unrecognisable. He wasn’t someone who wanted to live inside, because he felt he deserved to be out and deserved a hard time of it. But, ultimately, he had a belief in himself and he knew his limitations. If I offered him a room somewhere he would say, “I’m not going to cope with that now, I’m just going to go in and fail, I’d rather stay on the street.” His temper was like a devil on his back. He was scared of it. “I don’t dare go there, to that accommodation, because I don’t trust myself. I don’t care how freezing it is out here.” He knew that he had to avoid the hostel cycle: get in a room, get involved in drugs, get thrown out, go in again, get in a row with one of the staff or one of the residents, get thrown out, and on and on and on and on. But he is a deep thinker. He’s got everything weighed up, in a way. You tend to find that most people on the streets have a lot of time on their hands but, as a way of coping, either they fall into a mindset that will perpetuate homelessness or they don’t like to think too far because they reach painful things that have to be dealt with in order to move on. But Stuart was somebody who said, “Bring it on, bring the pain on, I want to face it.”’

The surface of the desk is covered with envelopes, pens and a pile of posters:

Stuart tells me that he has changed since he began working on the campaign. People have got friendlier. They’ve taken seriously what he has to say. When the open meeting at Wintercomfort was over he had asked for a role, and was immediately given one. ‘I was really surprised, to be honest,’ he says. ‘I thought middle-class people had something wrong with them. But they’re just ordinary. I was a bit shocked, to tell the truth.’

Stuart and I have given nine or ten talks together about the campaign since we began working together: in Birmingham, London, Oxford, in villages around Cambridge, to a hall full of university students at Anglia Polytechnic. We are the only people on the campaign who have the time to do it and we have developed a good pattern. I speak first, for twenty minutes, about the details of the case and push the petition or protest letter to the local MP or the forthcoming march in London, then Stuart gets up and knocks the audience out of its seat with a story of his life.

‘I am the sort of person these two dedicated charity workers were trying to help,’ he says, in effect. ‘Do you see what a nightmare I was? Do you see how difficult it would have been to govern a person like me? Do you see now why we should have awarded Ruth and John medals for what they were doing rather than sending them to prison for what they could not control?’

Sometimes in his talk a stray ‘fuck’ or ‘cunt’ will slip past and then he’ll blush or laugh, put a hand to his mouth in an unexpectedly girlish fashion and apologise for ‘me French’. He often ends by suggesting that the government kick out their current homelessness ‘tsar’ and employ Ruth instead. ‘I really do honestly believe that.’

Clap! Clap! Clap!

More often than not, a standing ovation.

This speech and tactic are entirely Stuart’s ideas. He does two things for the campaign: he folds letters and he exposes his soul.

‘Here, Alexander, you’ve missed the bus,’ exclaims Stuart. He has startled me from my ruminations. ‘There isn’t one for another two hours. Do you want to stay for supper?’

My heart sinks. More palm-shaped sarnies?

‘Me favourite – curry.’

I go out to the local shop and return with supplies. Bulgarian white for me; eight cans more of lager and a packet of tobacco for him.

‘What’s that you’re having? Wine? Ppwaaah!’ Stuart sniffs the bottle. ‘Smells like sick. Have a Stella.’

Curry is ‘Convict Curry’. His mother’s recipe. On very special occasions, he used to try to make it in the inmates’ kitchen in HMP Littlehey, where he was serving five years for robbing £1,000 and a fistful of cheques from a post office.

‘Mushrooms?’ A tin of buttons; Stuart tips the little foetuses in.

Then he opens a packet of no-label, super-economy frozen chicken quarters. Pallid and pockmarked, they look like bits of frosted chin, as if he did over a fat Eskimo last week. He extracts an onion from behind the toaster and begins hacking at it with one of his knives.

I finish my survey of his bedsit room.

The picture on the wall is of a place with mountains and a lazy blue lake. The plaster it covers is gashed down to the brickwork from one of his periodic bouts of ‘losing it’, when he gets into a sort of maelstrom of fury and – highly private occasions, these, he does not like to think about them – takes it out on the furniture and fittings. On the floor beside the desk is an empty carton of Shake n’ Vac, decorated in pink flowers.

‘Good stuff, that. Use it for anything. Like, see round the bed there? There should be a huge stain because I overdosed there last week. But just put Shake n’ Vac down. All the spilt cans and vomit – cleaned it up really well. Leave it for a week first though, before you hoover.’

The bills on the bedside cabinet are red.

No, Stuart does not mind if I rifle through them.

Cable: he has five extra channels, none of them sport, and no telephone. The reason homeless people use mobiles is because they’re much cheaper than ordinary phones if you take only incoming calls. In fact, with pay as you go, they cost nothing. It’s when the homeless start hanging around the public payphones that they’re doing what ordinary people suspect them of doing on their mobiles: ringing their dealers. Stuart never uses anything but public phones for that sort of call.

Water: Stuart receives a hardship grant from his water company, and has a number of slow-paying arrangements that are taken off his dole cheque at source. As with Latinate medical names, he is an expert at these pathetic calculations – much more in control of them than I am of mine. They are part of what is unpleasantly termed ‘life skills’. Not unreasonably, a person sleeping rough must display ‘life skills’ to his support workers if he is to be found a flat, otherwise he’ll simply fall into arrears, annoy everybody and get evicted.

‘On the street you get the same money as you get on housing, but now it’s half-grant, half-loan to furnish your flat,’ he explains, and gives the curry an encouraging prod. ‘You could be £15 a fortnight down paying back the loan. So, instead of £102, it’s now about £85. The water was fucking £26 a month before they remitted all me fines when I had the meter put in. And that was without electric and the gas and my TV licence. So out of £85 a fortnight I was paying £9 TV licence, £20 in electric because it was winter, £14 food minimum. Then you’ve got all your toiletries. I was making £49 outgoings go into £42.50. Even on pay day, your money don’t do the bills because as soon as you cash your giro you just want to go out. So first thing you do if you’ve been on the street is fuck the bills. The only thing I made sure is that I had leccy. Spices?’

‘How can you live on that, even without the bills?’

That’s the point. I don’t.’

Stuart rattles through the shelves above his draining board: economy tomatoes, economy baked beans, economy corn flakes – everything, except the beer, in white packaging with blue lines. Economy raisins, economy powdered milk, economy spaghetti; finally, at the back, Sharwood’s high-expense, in-a-glass-jar, multicoloured-label Five Spice, essential for Chinese cookery. He empties in all of it.