По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

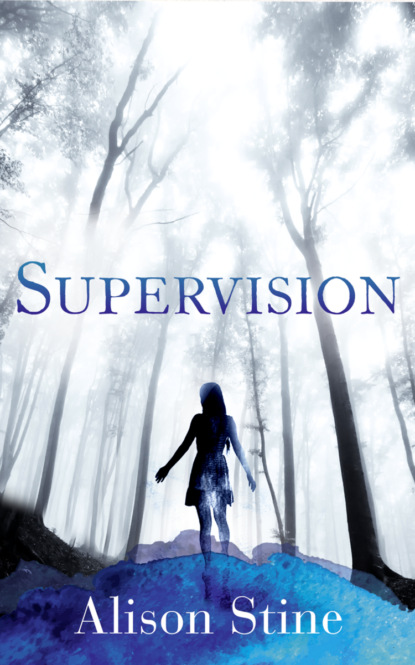

Supervision

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I had nightmares since my parents died. Not nightmares: dreams. I dreamed about a dark space. At the end of the space was a light, a bright white light growing brighter and bigger and whiter—and in the light, my mother danced.

I knew it was my mother, not my sister, although I had never actually seen my mother perform on stage. But the face on the dancer in my dreams matched the face I saw in pictures—like the Firecracker’s only thinner, a slimmer face than mine, with the high cheekbones I would never have, and the wrinkles on the forehead I didn’t have yet. It was the smile most of all that made me certain it was my mother. In photographs, she always smiled when she performed, and I knew—I remembered from seeing her on stage—my sister never did.

My sister grimaced. She grunted and frowned and stomped across the stage, a ball of energy, a lightning bolt. She danced like she was always angry. She tore through toe shoes. Her tutus ripped. Her feet bled. “The Firecracker,” The Times called her, and the name stuck. They also wrote that she was a tribute to her mother.

My sister quit dancing, right after that.

I didn’t really remember my mother, and I remembered my father only as a voice, a deep belly laugh. They died when I was a kid, in a car crash.

But I never dreamed about that.

In English, I tried to text, and the teacher saw. “Miss Wong,” she said. “Your phone, please.”

I slid out of my seat and dragged myself to the front. No one laughed until the third row, when a girl coughed and said it: “Miss Wrong.” Then everyone laughed, an explosion that radiated through the room. The teacher glared at the class, but didn’t say anything. I was getting a D, why would she?

After school, I had to double back to the classroom to pick up my phone, and I barely made the train. It was less crowded than yesterday, but slow, and the car I had picked had bad air-conditioning, the windows steaming over in the afternoon heat. Someone had cracked one open, a slit through which I could see the black tunnel. When we stopped at 168

Street, I could see something on one of the tunnel walls: graffiti. A tag. A name in bright green. I read it.

Acid.

There was more. There was a whole, terrible sentence.

Acid Loves You.

It wasn’t my stop, but I pushed out of the car just as the doors were starting to close. My bag got stuck, and I yanked it free, nearly falling onto the platform. People were staring, but I didn’t care.

The train began to pull away and I looked around. Everyone who had gotten off went up the stairs to street level. With a shudder, the train left too. And I could see it now, the stupid graffiti, see it clearly: Acid Loves You. It was painted in bright green, the color of acid, almost florescent in the dark tunnel.

The subway platform where people waited was tiled in white, but in the tunnel through which the trains traveled, the walls were black. It was here that the message had been painted. Someone had climbed down from the platform, and into the tunnel to do it.

The platform ended at the mouth of the tunnel, at a sign that read CAUTION: DO NOT ENTER. But a little walkway continued into the tunnel beyond the sign, an access path for subway workers. I looked down this little walkway, peering into darkness. The only light came from the work bulbs strung across the ceiling every few feet, and the signal light: a kind of traffic light for trains.

The signal light was red, which meant no train was coming.

I glanced behind me. There were only a few people waiting for the downtown train. No one was looking. I stepped over the sign, crept onto the walkway—and went into the tunnel.

I wanted to see the graffiti up close. It had to be from my friend, it had to be. How many people in our neighborhood were called Acid? I balanced on the narrow walkway. There was a railing, but it was low and spindly. It wouldn’t hold me if I fell.

I just wouldn’t fall, I told myself.

The graffiti was only a few feet inside the tunnel, painted on the wall a little above my head. Whoever had written it hadn’t been much taller than me—and they were sloppy; a line of green paint trailed down the tunnel. I followed the paint splatter, crouching until I was kneeling, until the paint disappeared into the wall.

Into the wall?

I spread my palms, scanning the wall. It felt smooth. Then I felt a rough line. I worked my fingers into the crack and pulled until a door popped open. It was a small space, a crawl space, little more than a hole, and inside was darkness—and green polka dots.

Inside the door in the wall, green paint spotted the floor, so bright it glowed. I didn’t think; I crawled. I pushed in, my knees dragging on cement, trying to examine the paint.

With a groan, the door to the crawl space swung shut behind me. My chest swelled and I couldn’t breathe. I shot forward, knocking my forehead into a wall. Pain. Then everything was blackness.

When I woke, it took a moment for me to remember where I was. Panic returned. I was cold and stuck in the subway tunnel, in some sort of recess. I couldn’t turn around so I pushed back as hard as I could, shoving my backpack against the door. It swung open and I fell out onto the tunnel walkway.

A light was moving in the tunnel, jostling up and down. I stood. I wanted to run, but I was afraid I would fall. I saw a man beneath the moving light. The light was attached to him, a big headlamp, and he was running, coming right at me. I would have been scared, except he looked funny with the oversized headlamp, like a kid playing dress up. He wore a pair of overalls, and they were filthy, as was his shirt. Even his face was smeared with dirt.

“Child,” he said. He waved his arms. “Child, get out of here. A train is coming.”

“No, it’s not,” I said. “The light is red.”

“The light?” he said, confused.

“The signal light.” I pointed behind me, then turned back to the man to show him, but he was gone. The tunnel was empty. And I felt something behind me. Arms wrapped around my waist and lifted, grabbing me, yanking me out of the tunnel.

It was another man, another subway worker who had grabbed me. He wore a bright orange and yellow safety vest, goggles, no headlamp—and there was a policewoman with him. The radio on the cop’s shoulder squawked.

“We got her,” the officer said into the radio.

Out on the platform, a crowd had gathered.

The subway worker was sweating. He set me down on the platform, and wiped his forehead with his hand. “Girl,” he said. “You are in so much trouble.”

And I was.

CHAPTER 2: (#u3e028c1f-f68b-5d7d-9e56-bfeb42ffb2e6)

Wellstone (#u3e028c1f-f68b-5d7d-9e56-bfeb42ffb2e6)

My sister dragged the old suitcases out of the closet, and swung them onto my bed. She clicked them open, one after the other.

“What are you doing?” I asked.

“Packing,” she said.

“Where are you going?”

“I’m packing for you.”

“Where am I going?”

She looked at me. “You know.”

The nightmares that night were different. No dancing. No mom. No tunnel even, despite the fact that I had just been pulled from one, despite the fact that the police had taken me to a corner of the station, and asked me: What was I doing? How could I have been so dumb? Didn’t I know I could have been killed? Didn’t I know people died that way? Just a few months ago, in this very tunnel.

I knew, I knew, I told them. I said I was sorry.

The first few times I told the story, I told about the man with the headlamp and the dirty clothes. But no one knew who the man was. So I stopped telling that part. When my sister showed up, the police let me go. No fine. This time. And no court appearance because the Firecracker was taking me out of state.

She promised.