По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

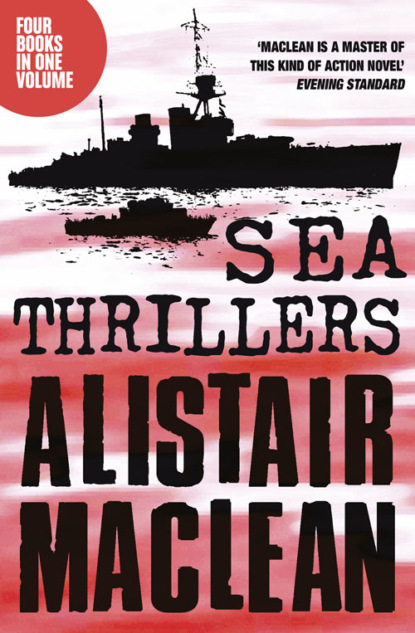

Alistair MacLean Sea Thrillers 4-Book Collection: San Andreas, The Golden Rendezvous, Seawitch, Santorini

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Luftwaffe officers shouldn’t tell fibs. Of course I understand. I understand that the only foreseeable emergency is that you run short of supplies and the only reason you’re not coming below is that we don’t serve malt whisky with ward dinners.’

The Lieutenant shook his head in sadness. ‘I am deeply wounded.’

‘Wounded!’ she said. They had returned to the hospital mess-deck. ‘Wounded.’

‘I think he is.’ McKinnon looked at her in speculative amusement. ‘And you, too.’

‘Me? Oh, really!’

‘Yes. Really. You’re hurt because you think he prefers Scotch to your company. Isn’t that so?’ She made no reply. ‘If you believe that, then you’ve got a very low opinion of both yourself and the Lieutenant. You were with him for about an hour tonight. What did he drink in that time?’

‘Nothing.’ Her voice was quiet.

‘Nothing. He’s not a drinker and he’s a sensitive lad. He’s sensitive because he’s an enemy, because he’s a captive, a prisoner of war and, of course, he’s sensitive above all because he’s now got to live all his life with the knowledge that he killed fifteen innocent people. You asked him if he was coming down. He didn’t want to be asked “if”. He wanted to be persuaded, even ordered. “If” implies indifference and the way he’s feeling it could be taken for a rejection. So what happens? The ward sister tells her feminine sympathy and intuition to take a holiday and delivers herself of some cutting remarks that Margaret Morrison would never have made. A mistake, but easy enough to put right.’

‘How?’ The question was a tacit admission that a mistake had indeed been made.

‘Ninny. You take his hand and say sorry. Or are you too proud?’

‘Too proud?’ She seemed uncertain, confused. ‘I don’t know.’

‘Too proud because he’s a German? Look, I know about your fiancé and brother and I’m terribly sorry but that doesn’t –’

‘Janet shouldn’t have told you.’

‘Don’t be daft. You didn’t object to her telling you about my family.’

‘And that’s not all.’ She sounded almost angry. ‘You said they went around killing thousands of innocent people and that –’

‘Those were not my words. Janet did not say that. You’re doing what you accused the Lieutenant of doing – fibbing. Also, you’re dodging the issue. Okay, so the nasty Germans killed two people you knew and loved. I wonder how many thousands they killed before they were shot down. But that doesn’t matter really, does it? You never knew them or their names. How can you weep over people you’ve never met, husbands and wives, sweethearts and children, without faces or names? It’s quite ridiculous, isn’t it, and statistics are so boring. Tell me, did your brother ever tell you how he felt when he went out in his Lancaster bomber and slaughtered his mother’s fellow countrymen? But, of course, he’d never met them so that made it all right, didn’t it?’

She said in a whisper: ‘I think you’re horrible.’

‘You think I’m horrible. Janet thinks I’m a heartless fiend. I think you’re a pair of splendid hypocrites.’

‘Hypocrites?’

‘You know – Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. The ward sister and Margaret Morrison. Janet’s just as bad. At least I don’t deal in double standards.’ McKinnon made to leave but she caught him by the arm and indulged, not for the first time, in the rather disconcerting practice of examining each of his eyes in turn.

‘You didn’t really mean that, did you? About Janet and myself being hypocrites?’

‘No.’

‘You are devious. All right, all right, I’ll make it right with him.’

‘I knew you would. Margaret Morrison.’

‘Not Ward Sister Morrison?’

‘You don’t look like Mrs Hyde.’ He paused. ‘When were you to have been married?’

‘Last September.’

‘Janet. Janet and your brother. They were pretty friendly, weren’t they?’

‘Yes. She told you that?’

‘No. She didn’t have to.’

‘Yes, they were pretty friendly.’ She was silent for a few moments. ‘It was to have been a double wedding.’

‘Oh hell,’ McKinnon said and walked away. He checked all the scuttles in the hospital area – even from the relatively low altitude of a submarine conning-tower the light from an uncovered porthole can be seen for several miles – went down to the engine-room, spoke briefly to Patterson, returned to the mess-deck, had dinner, then went into the wards. Janet Magnusson, in Ward B, watched his approach without enthusiasm.

‘So you’ve been at it again.’

‘Yes.’

‘Do you know what I’m talking about?’

‘No. I don’t know and I don’t care. I suppose you’re talking about your friend Maggie – and yourself. Of course I’m sorry for you both, terribly sorry, and maybe tomorrow or when we get to Aberdeen I’ll break my heart for yesterday. But not now, Janet. Now I have one or two more important things on my mind such as, say, getting to Aberdeen.’

‘Archie.’ She put a hand on his arm. ‘I won’t even say sorry. I’m just whistling in the dark, don’t you know that, you clown? I don’t want to think about tomorrow.’ She gave a shiver, which could have been mock or not. ‘I feel funny. I’ve been talking to Maggie. It’s going to happen tomorrow, isn’t it, Archie?’

‘If by tomorrow you mean when daylight comes, then, yes. Could even be tonight, if the moon breaks through.’

‘Maggie says it has to be a submarine. So you said.’

‘Has to be.’

‘How do you fancy being taken a prisoner?’

‘I don’t fancy it at all.’

‘But you will be, won’t you?’

‘I hope not.’

‘How can you hope not? Maggie says you’re going to surrender. She didn’t say so outright because she knows we’re friends – we are friends, Mr McKinnon?’

‘We are friends, Miss Magnusson.’

‘Well, she didn’t say so, but I think she thinks you’re a bit of a coward, really.’

‘A very – what’s the word, perspicacious? – a very perspicacious girl is our Maggie.’

‘She’s not as perspicacious as I am. You really think there’s a chance we’ll reach Aberdeen?’

‘There’s a chance.’