По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

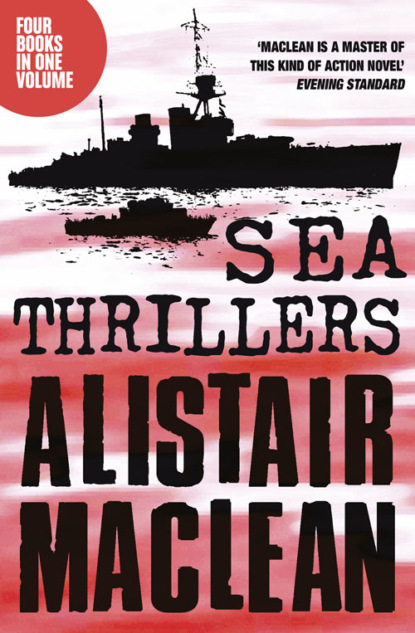

Alistair MacLean Sea Thrillers 4-Book Collection: San Andreas, The Golden Rendezvous, Seawitch, Santorini

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Not only that but you’ve made me feel very, very foolish.’

‘I have? I would never do that.’

‘You did. Remember on the bridge you suggested – in jest, of course – that you might fight the U-boat with a fusillade of stale bread and old potatoes. Well, something like that.’

‘Ah!’

‘Yes, ah! Remember that emotional scene on the bridge – well, emotional on my part, I cringe when I think about it – when I begged you to fight them and fight them and fight them. You remember, don’t you?’

‘Yes, I think I do.’

‘He thinks he does! You had already made up your mind to fight them, hadn’t you?’

‘Well, yes.’

‘Well, yes,’ she mimicked. ‘You had already made up your mind to ram that U-boat.’

‘Yes.’

‘Why didn’t you tell me, Archie?’

‘Because you might have casually mentioned it to somebody who might have casually mentioned it – unknowingly, of course – to Flannelfoot who would far from casually have mentioned it to the U-boat captain who would have made damn certain that he would never put himself in a position where he could be rammed. You might even – again unknowingly – have mentioned it directly to Flannelfoot.’

She made no attempt to conceal the hurt in her eyes. ‘So you don’t trust me. You said you did.’

‘I trust you absolutely. I did say that.’

‘Then why –’

‘It was one of those then-and-now things. Then you were Sister Morrison. I didn’t know there was a Margaret Morrison. I know now.’

‘Ah!’ She pursed her lips, then smiled, clearly mollified. ‘I see.’

McKinnon left her, joined Dr Sinclair and Jamieson, and together they went to the door of the recovery room. Jamieson was carrying with him an electric drill, a hammer and some tapered wooden pegs. Jamieson said: ‘You saw the entry hole made by the shell when you went up to examine the bows?’

‘Yes. Just on – well, an inch or two above – the waterline. Could be water inside. Or not. It’s impossible to say.’

‘How high up?’

‘Eighteen inches, say. Anybody’s guess.’

Jamieson plugged in his drill and pressed the trigger. The tungsten carbide bit sank easily into the heavy steel of the door. Sinclair said: ‘What happens if there’s water behind?’

‘Tap in one of those wooden pegs, then try higher up.’

‘Through,’ Jamieson said. He withdrew the bit. ‘Clear.’

McKinnon struck the steel handle twice with the sledge. The handle did not even budge a fraction of an inch. On the third blow it sheared off and fell to the deck.

‘Pity,’ McKinnon said. ‘But we have to find out.’

Jamieson shrugged. ‘No option. Torch?’

‘Please.’ Jamieson left and was back in two minutes with the torch, followed by McCrimmon carrying the gas cylinder and a lamp on the end of a wandering lead. Jamieson lit the oxy-acetylene flame and began to carve a semi-circle round the space where the handle had been: McCrimmon plugged in the wandering lead and the wire-caged lamp burned brightly.

Jamieson said from behind his plastic face-shield: ‘We’re only assuming that this is where the door is jammed.’

‘If we’re wrong we’ll cut away round the hinges. I don’t think we’ll have to. The door isn’t buckled in any way. It’s nearly always the lock or latch that’s jammed.’

The compartment was filled with stinging acrid smoke when Jamieson finally straightened. He gave the lock a couple of blows with the side of his fist, then desisted.

‘I’m sure I’ve cut through but the damn thing doesn’t seem to want to fall away.’

‘The latch is still in its socket.’ McKinnon tapped the door with his sledge, not heavily, and the semi-circular piece of metal fell away inside. He hit the door again, heavily this time, and it gave an inch. With a second blow it gave several more inches. He laid aside the sledge and pushed against the door until, squeaking and protesting, it was almost wide open. He took the wandering lead from McCrimmon and went inside.

There was water on the deck, not much, perhaps two inches. Bulkheads and deckhead had been heavily starred and pock-marked by shrapnel from the exploding shell. The entrance hole formed by the shell in the outer bulkhead was a jagged circle not more than a foot above the deck.

The two men from the Argos were still lying in their beds while Dr Singh, head bowed to his chest, was sitting in a small armchair. All three men seemed unharmed, unmarked. The Bo’sun brought the light closer to Dr Singh’s face. Whatever shrapnel may have been embedded in his body, none had touched his face. The only sign of anything untoward were tiny trickles of blood from his ears and nose. McKinnon handed the lamp to Dr Sinclair, who stooped over his dead colleague.

‘Good God! Dr Singh.’ He examined him for a few seconds, then straightened. ‘That this should happen to a fine doctor, a fine man like this.’

‘You didn’t really expect to find anything else, did you, Doctor?’

‘No. Not really. Had to be this or something like this.’ He examined, briefly, the two men lying in their beds, shook his head and turned away. ‘Still comes as a bit of a shock.’ It was obvious that he was referring to Dr Singh.

McKinnon nodded. ‘I know. I don’t want to sound callous, Doctor, I know it might sound that way, but – you won’t be needing those men any more? I mean, no postmortems, nothing of that kind.’

‘Good lord, no. Death must have been instantaneous. Concussion. If it’s any consolation, they died without knowing.’ He paused. ‘You might look through their clothing, Bo’sun. Or maybe it’s in their effects or perhaps Captain Andropolous has the details.’

‘You mean names, birth-dates, things like that, sir?’

‘Yes. I have to fill out the death certificates.’

‘I’ll attend to that.’

‘Thank you, Bo’sun.’ Sinclair essayed a smile but it could hardly have been rated as a success. ‘As usual, I’ll leave the grisly part to you.’ With that he was gone, a man glad to be gone. The Bo’sun turned to Jamieson.

‘Could I borrow McCrimmon, sir?’

‘Of course.’

‘McCrimmon, go and find Curran and Trent, will you? Tell them what’s happened. Curran will know what size of canvases to bring.’

‘Needles and thread, Bo’sun?’

‘Curran is a sailmaker. Just leave it to him. And you could tell him that it’s a clean job this time.’

McCrimmon left and Jamieson said: ‘A clean job? It’s a lousy job. You always get the dirty end of the stick, McKinnon. I honestly don’t know how you keep on doing it. If there’s anything nasty or unpleasant to be done, you’re number one on everybody’s list.’