По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

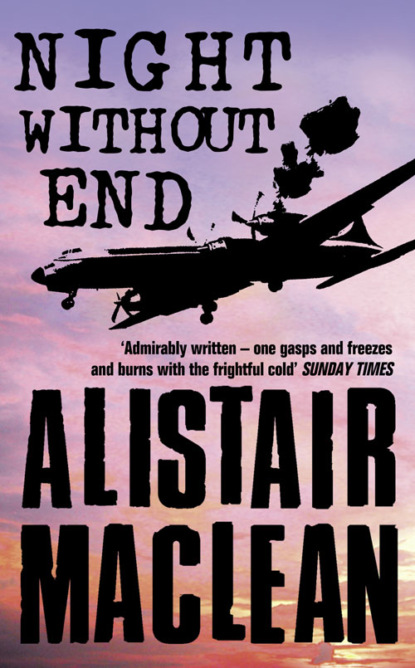

Alistair MacLean Arctic Chillers 4-Book Collection: Night Without End, Ice Station Zebra, Bear Island, Athabasca

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Later. Let me have a quick look at that back of yours.’

‘Look at what?’

‘Your back,’ I said patiently. ‘Your shoulders. They seem to give you some pain. I’ll rig a screen.’

‘No, no, I’m all right.’ She moved away from me.

‘Don’t be silly, my dear.’ I wondered what trick of voice production made Marie LeGarde’s voice so clear and carrying. ‘He is a doctor, you know.’

‘No!’

I shrugged and reached for my brandy glass. Bearers of bad news were ever unpopular: I supposed her reaction was the modern equivalent of the classical despot’s unsheathing his dagger. Probably only bruises, anyhow, I told myself, and turned to look at the company.

An odd-looking bunch, to say the least, but then any group of people dressed in lounge suits and dresses, trilby hats and nylon stockings would have looked odd against the strange and uncompromising background of that cabin where every suggestion of anything that even remotely suggested gracious living had been crushed and ruthlessly made subservient to the all-exclusive purpose of survival.

Here there were no armchairs – no chairs, even – no carpets, wall-paper, book-shelves, beds, curtains – or even windows for the curtains. It was a bleak utilitarian box of a room, eighteen feet by fourteen. The floor was made of unvarnished yellow pine. The walls were made of spaced sheets of bonded ply, with kapok insulation between: the lower part of the walls was covered with green-painted asbestos, the upper part and entire roof sheeted with glittering aluminium to reflect the maximum possible heat and light. A thin, ever-present film of ice climbed at least halfway up all four walls, reaching almost to the ceiling in the four corners, the parts of the room most remote from the stove and therefore the coldest. On very cold nights, such as this, the ice reached the ceiling and started to creep across it to the layers of opaque ice that permanently framed the undersides of our rimed and opaque skylights.

The two exits from the cabin were let into the fourteen-foot sides: one led to the trap, the other to the snow and ice tunnel where we kept our food, petrol, oil, batteries, radio generators, explosives for seismological and glacial investigations and a hundred and one other items. Half-way along, a secondary tunnel led off at right angles – a tunnel which steadily increased in length as we cut out the blocks of snow which were melted to give us our water supply. At the far end of the main tunnel lay our primitive toilet system.

One eighteen-foot wall and half of the wall that gave access to the trap-door were lined with twin rows of bunks – eight in all. The other eighteen-foot wall was given over entirely to our stove, work-bench, radio table and housings for the meteorological instruments. The remaining wall by the tunnel was piled with tins and cases of food, now mostly empties, that had been brought in from the tunnel to begin the lengthy process of defrosting.

Slowly I surveyed all this, then as slowly surveyed the company. The incongruity of the contrast reached the point where one all but disbelieved the evidence of one’s own eyes. But they were there all right, and I was stuck with them. Everyone had stopped talking now and was looking at me, waiting for me to speak: sitting in a tight semi-circle round the stove, they were huddled together and shivering in the freezing cold. The only sounds in the room were the clacking of the anemometer cups, clearly audible down the ventilation pipe, the faint moaning of the wind on the ice-cap and the hissing of our pressure Colman lamp. I sighed to myself, and put down my empty glass.

‘Well, it looks as if you are going to be our guests for some little time, so we’d better introduce ourselves. Us first.’ I nodded to where Joss and Jackstraw were working on the shattered RCA, which they had lifted back on the table. ‘On the left, Joseph London, of the city of London, our radio operator.’

‘Unemployed,’ Joss muttered.

‘On the right, Nils Nielsen. Take a good look at him, ladies and gentlemen. At this very moment the guardian angels of your respective insurance companies are probably putting up a prayer for his continued well-being. If you all live to come home again, the chances are that you will owe it to him.’ I was to remember my own words later. ‘He probably knows more than any man living about survival on the Greenland ice-cap.’

‘I thought you called him “Jackstraw”,’ Marie LeGarde murmured.

‘My Eskimo name.’ Jackstraw had turned and smiled at her, his parka hood off for the first time; I could see her polite astonishment as she looked at the fair hair, the blue eyes, and it was as if Jackstraw read her thoughts. ‘Two of my grandparents were Danish – most of us Greenlanders have as much Danish blood as Eskimo in us nowadays.’ I was surprised to hear him talk like this, and it was a tribute to Marie LeGarde’s personality: his pride in his Eskimo background was equalled only by his touchiness on the subject.

‘Well, well, how interesting.’ The expensive young lady was sitting back on her box, hands clasped round an expensively-nyloned knee, her expression reflecting accurately the well-bred condescension of her tone. ‘My very first Eskimo.’

‘Don’t be afraid, lady.’ Jackstraw’s smile was wider than ever, and I felt more than vaguely uneasy; his almost invariable Eskimo cheerfulness and good nature concealed an explosive temper which he’d probably inherited from some far distant Viking forebear. ‘It doesn’t rub off.’

The silence that followed could hardly be described as companionable, and I rushed in quickly.

‘My own name is Mason, Peter Mason, and I’m in charge of this IGY station. You all know roughly what we’re doing stuck out here on the plateau – meteorology, glaciology, the study of the earth’s magnetism, the borealis, airglow, ionosphere, cosmic rays, magnetic storms and a dozen other things which I suppose are equally uninteresting to you.’ I waved my arm. ‘We don’t, as you can see, normally live here alone. Five others are away to the north on a field expedition. They’re due back in about three weeks, after which we all pack up and abandon this place before the winter sets in and the ice-pack freezes on the coast.’

‘Before the winter sets in?’ The little man in the Glenurquhart jacket stared at me. ‘You mean to tell me it gets colder than this?’

‘It certainly does. An explorer called Alfred Wegener wintered not fifty miles from here in 1930–1, and the temperature dropped by 85 degrees below zero – 117 degrees of frost. And that may have been a warm winter, for all we know.’

I gave some time to allow this cheering item of information to sink in, then continued.

‘Well, that’s us. Miss LeGarde – Marie LeGarde – needs no introduction from anyone.’ A slight murmur of surprise and turning of heads showed that I wasn’t altogether right. ‘But that’s all I know, I’m afraid.’

‘Corazzini,’ the man with the cut brow offered. The white bandage, just staining with blood, was in striking contrast to the receding dark hair. ‘Nick Corazzini. Bound for Bonnie Scotland, as the travel posters put it.’

‘Holiday?’

‘No luck.’ He grinned. ‘Taking over the new Global Tractor Company outside Glasgow. Know it?’

‘I’ve heard of it. Tractors, eh? Mr Corazzini, you may be worth your weight in gold to us yet. We have a broken-down elderly tractor outside that can usually only be started by repeated oaths and assaults by a four-pound hammer.’

‘Well.’ He seemed taken aback. ‘Of course, I can try—’

‘I don’t suppose you’ve actually laid a finger on a tractor for many years,’ Marie LeGarde interrupted shrewdly. ‘Isn’t that it, Mr Corazzini?’

‘Afraid it is,’ he admitted ruefully. ‘But in a situation like this I’d gladly lay my hands on another one.’

‘You’ll have your chance,’ I promised him. I looked at the man beside him.

‘Smallwood,’ the minister announced. He rubbed his thin white hands constantly to drive the cold away. ‘The Reverend Joseph Smallwood. I’m the Vermont delegate to the international General Assembly of the Unitarian and Free United Churches in London. You may have heard of it – our biggest conference in many years?’

‘Sorry.’ I shook my head. ‘But don’t let that disturb you. Our paper boy misses out occasionally. And you, sir?’

‘Solly Levin. Of New York City,’ the little man in the check jacket added unnecessarily. He reached up and laid a proprietary arm along the broad shoulders of the young man beside him. ‘And this is my boy, Johnny.’

‘Your boy? Your son?’ I fancied I could see a slight resemblance.

‘Perish the thought,’ the young man drawled. ‘My name is Johnny Zagero. Solly is my manager. Sorry to introduce a discordant note into company such as this’ – his eyes swept over us, dwelt significantly longer on the expensive young lady by his side – ‘but I’m in the way of being a common or garden pugilist. That means “boxer”, Solly.’

‘Would you listen to him?’ Solly Levin implored. He stretched his clenched fists heavenwards. ‘Would you just listen to him? Apologisin’. Johnny Zagero, future heavyweight champion, apologisin’ for being a boxer. The white hope for the world, that’s all. Rated number three challenger to the champ. A household name in all—’

‘Ask Dr Mason if he’s ever heard of me,’ Zagero suggested.

‘That means nothing,’ I smiled. ‘You don’t look like a boxer to me, Mr Zagero. Or sound like one. I didn’t know it was included in the curriculum at Yale. Or was it Harvard?’

‘Princeton,’ he grinned. ‘And what’s so funny about that? Look at Tunney and his Shakespeare. Roland La Starza was a college boy when he fought for the world title. Why not me?’

‘Exactly.’ Solly Levin tried to thunder the word, but he hadn’t the voice for it. ‘Why not? And when we’ve carved up this British champ of yours – a doddery old character rated number two challenger by one of the biggest injustices ever perpetrated in the long and glorious history of boxin’ – when we’ve massacred this ancient has-been, I say—’

‘All right, Solly,’ Zagero interrupted. ‘Desist. There’s not a press man within a thousand miles. Save the golden words for later.’

‘Just keepin’ in practice, boy. Words are ten a penny. I’ve got thousands to spare—’

‘T’ousands, Solly, t’ousands. You’re slippin’. Now shut up.’

Solly shut up, and I turned to the girl beside Zagero.

‘Well, miss?’

‘Mrs. Mrs Dansby-Gregg. You may have heard of me?’

‘No.’ I wrinkled my brow. ‘I’m afraid I haven’t.’ I’d heard of her all right, and I knew now that I’d seen her name and picture a score of times among those of other wealthy unemployed and unemployable built up by the tongue-in-the-cheek gossip columnists of the great national dailies into an ersatz London society whose frenetic, frequently moronic and utterly unimportant activities were a source of endless interest to millions. Mrs Dansby-Gregg, I seemed to recall, had been particularly active in the field of charitable activities, although perhaps not so in the production of the balance sheets.