По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

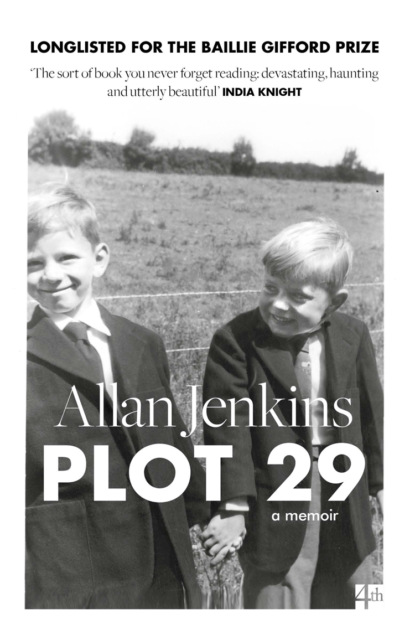

Plot 29: A Memoir: LONGLISTED FOR THE BAILLIE GIFFORD AND WELLCOME BOOK PRIZE

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The slugs may be winning their battle with the climbing beans. The early salads have bolted. The garlic and shallots that had looked green and healthy only a few days ago have succumbed to papery rust and need to be pulled. The wild Tuscan calendula has spread like duckweed and is smothering other plants. For my first time in June, the plot is in need of a reboot. The living carpet that normally covers the soil is threadbare and worn. A couple of weeks before midsummer I start again. It is hard sometimes not to think that your garden says something about you, the green fingers you hope you have, your innate ability (or inability) to nurture. Hard not to feel good about yourself when the plot thrives, or like a failure when it falls. The fault must be yours and not the seed, the weather or blight on the site.

Without early success at growing as a kid, I guess, I might not be doing it now. It was the first time as a child I thought I might be gifted at something. In south Devon, Dudley gave Christopher and me two pocket-sized patches of garden and two packets of seed. Christopher had African marigolds (tagetes): bright orange, cheery, the stuff of temple garlands. I was handed nasturtium flowers: chaotic cascades of reds, oranges and yellows (Dad liked bright colours), which soon overflowed. Caper-shaped seed heads would dry in the sun. I was amazed (still am) that so much life can come from a small packet. Later my nasturtiums would fall prey to black fly, a nightmare infestation sucking sugary life. Lilian showed me how to spray leaves and stems with soapy water, holding back the devastation until frost would turn their green into limp, ghostly grey; a silvery sheen of dew signalling the end. I would pull them, shake out seed for next year (though the self-seeding was always enough) and throw the lifeless bodies on the compost pile to rot down and turn into soil. This idea of nature’s renewal fascinated me. I was in love.

For the first few years at the allotment I helped with a primary school’s gardening club, where children from five to 11 learned to grow. Kids who might be having trouble settling in class worked together during Friday lunchtimes. Seedlings grown in the greenhouse were replanted in raised beds in the playground. I would host their visits to the site. Branch Hill, where we are, is like a Victorian secret garden: gated, only just domesticated, sheltered by tall trees. We would give the children sunflower seeds and watch them stand, stunned, as the plants grew faster than them. We would eat peas from the pod and taste herbs. One memory sticks: watching the blossoming of a Somali-born girl. At first head down and standing shyly at the back of the group, she began to join in, to enquire about sorrel, lovage and other flavours unfamiliar to her. By the end of the year, impatient at the gate, she would rush to ask for magic nasturtium, her favourite ‘spicy flower’.

1960. Christopher is morphing from an undersized child into a fast-growing boy. The nervous reserve is fading too. He is talking more often, more excitedly. Always out with his fishing rod or digging for bait. I don’t have the stomach for threading anxious ragworm on to a hook. We never eat fish he has caught. He never brings it home. He doesn’t like fish for tea anyway. He is a meat and potato boy. His favourite: Heinz spaghetti on toast. He gradually drifts towards the village. He can more clearly hear its call: the dog whistle of other kids. I see them on the hills, on the horizon, like spotting a fox. Within a few years he is a natural athlete, gifted at sport. He is better at being a boy than me. He is more natural. Cars and bikes, cricket and football; later, beer with bigger lads. Soon after we arrive, Dudley builds us a push cart. He paints it bright yellow and blue. Chris’s freckled face brightens as we tear down the hill behind the house, laughing as we hurtle towards the river, skewing across the tidal road, the wooden handbrake screaming as we mostly avoid the mud. He is gradually healing from his fear. He is gaining height and weight. After a few years of living in Aveton Gifford he is an annoying inch taller than me.

I am back at the plot and the snails are still rampant on Mary’s patch. I am not sure why. I have cleared a lot of weed and there are few secret places left to hide. Maybe it is just their year. I have sown and re-sown peas and beans but they cull the baby shoots almost every time. Skeletal seedlings lie at the base of the poles. It’s a bean battlefield. I succumb, finally, to buying organic pellets. The biodynamic thought-police would frown but I cannot have thriving crops while Mary’s wigwam is bare. I restock French beans (in three colours: yellow, green and blue) and go up one evening after work. The site is empty, smelling of hay and English summer. Clumps of calendula almost shine through the early gloom. I sow more beans at the base of Mary’s poles and uncover the first stirrings of last week’s seed, sprouts curled like dormice. I replenish the pea sticks and scatter protective pellets. Time is starting to run out. We are a week from the solstice and I won’t be here to help. I am heading to the other magical piece of land in my life, a summerhouse plot on the East Jutland coast, where I plant mostly trees.

It is always odd leaving the allotment for any length of time. I feel as if I am abandoning it and it won’t understand. It is a recurring irrational feeling (a theme through my life like a name through seaside rock). But it is stronger now, reinforced by my enforced absence over the winter with broken bones.

The Danish plot is different. It is an echo of Devon. Coastal, even the wide stretch of shallow water and white sand is the same. Here the garden is larger, wilder, more isolated than in London – about 1,500 square metres of sandy loam 300 metres from the sea and a few kilometres from where my 90-year-old Danish mother-in-law lives. Close enough for her to cycle.

We have had this house and land for 10 years now. It is maybe my safest place.

Of course, there are many echoes of Dudley, of our house, Herons Reach, of home. They are here in the climate, in the light, in the anxious dragonflies, the blue butterflies, in the flowers: pink campions in summer, pale primroses in spring – the same shy, unassuming flower I used to pick for Lilian on Mothering Sunday. Here in the finches and tits we feed, in the sudden arrival of migrating flocks that stop off to feast on the wild cherry trees, the red-berried rowan. Here in the orange-backed hares that lope through the meadow, the foxes and badgers that leave tracks in the snow. In the brambles that line the beach, conjuring comforting images of late-summer days, picking through hedges with Lilian, packing small churns with berries, my hands and face stained with juice. Perhaps most of all the memories are in making the blackberry and apple pies that Dudley adored with buttery Devon cream (Lilian was not a gifted cook but she could make a good pie). Yet the deepest Devon echoes are in the trees. Dudley loved to plant trees: poplar and laburnum to line the new drive to the house, Japanese cherry for the autumn-colouring leaf I liked to press between pages of my exercise book; apple (Cox’s Orange Pippin for eating, Bramley for cooking), Conference pears and Victoria plums. When I was about seven he planted 200 six-inch Christmas trees it was my job to look after, to trim the choking grass. This was my least favourite chore, worse even than raking the acres of endless lawn. The tiny trees were fiddly, with no hiding place if the shears skipped and a stem was severed. Christopher escaped this because he chopped too many trees. Smart like a fox, my brother.

Perhaps in honour of Dudley, though it is never as explicit as this implies, I grow mostly trees here on Ahl – a few old Danish varieties of apple and plum, three espalier pears, red and blackcurrant bushes, with pine, fir, larch, birch and beech. They are chosen to fit in with the area, a peninsula of old plantations with wooden summerhouses dotted through. When we first found the house, we had to cut down senile trees that surrounded the plot. We chopped them with the help of our neighbours, the same neighbours who gave up weekends to build a shed for the wood they helped saw and split for the stove; the same neighbours who light our morning fire in winter before we arrive. Solitude plus community, the constant I search for, the same as the allotment, an echo of a Devon village life that no longer exists and to which I never belonged.

As with the allotment, I lie wondering about the plot when I am not there, suffering the same wrench when I leave. I sow tulip bulbs in the border in winter with only a slight chance I will see them bloom. The appeal lies in knowing they are part of a dialogue with their surroundings. I am happy if my visits coincide with flowering but I don’t have to be here at the time. Finding the spent flowers, petals fallen, their colours faded, is enough. Like the allotment, it is the growing that is the thing. Although I take childish delight in seeing the larch shoot up, reach for the sky, I know I most likely won’t see it at its majestic best as a mature tree. But someone will, maybe a small boy as he swings on it or plays in the summer grass. In the meantime I mow, and occasionally remember Dudley carving lawn and meadow and orchard out of field and Devon hill, his beret on (like him, perhaps, a relic from wartime), his neatly trimmed military moustache (ditto), his tightly belted corduroy trousers, grass-green stains on his shoes, and I watch and wait.

I see the larch outstrip the three new birch while its sister tree picks up sunlight and shadow in the other corner. I watch the new, soft green shoots from the saplings bought from an ad in the local paper. I sometimes move the small trees around in the plot until they find their spot and settle. I watch the wild rugosa rose take and spread. The local authority has a love-hate relationship with the sprawling, fragrant flower banks that line the length of the beach, razing them to the ground every year. They are Russian, they say, though the beach has had the roses as long as anyone remembers. The Danes have a conflicted relationship with invasive outsiders, though I, of course, root for the rugosa.

I watch the shy redshanks flutter and feed on ants in the evening. The male calls his morning warning as I pass the bird box they return to every year (I turn left, walking the long way around the house so as not to upset them). I observe the spotted woodpecker train its fledgling in feeding while a tit craftily creeps up behind them in case they miss anything. I listen to the blackbirds as the male sings from the highest branch of the tallest birch and as pairs patrol the lawn, puffed up and important. With these too, I avoid the woodshed when they nest there, a nuisance on cooler Nordic mornings if I want to light a fire.

I admire the starburst of wildflowers on the south side of the house: one year a swooning bank of scarlet poppies, the next year ox-eye daisy, then nothing. I obsessively buy and scatter wild meadow seed to little or no effect. I plant new banks of beech to replace some of the seclusion lost when the tree surgeon ran rampant through the plot. I move the Reine Claude plum to see if it is happier in a slightly shadier spot. Mostly though I train my eye to see the small changes since my last visit: the jewel-coloured beetles, the frogs, the trefoil, the shy hepatica flower, as I lie in the dew for a closer look on my ritual morning walkabout. Everything here is geared towards spring and summer, to the new leaf that shuts out the neighbouring plots, pushes them away, electric green walls if you will, infested with teeming new life, the all-day dawn chorus.

SUNDAY MORNING, LATE JUNE. I am on the first bus, my travelling companions the domestic workers heading to Hampstead, to the larger London homes they clean and care for. I haven’t been here for a fortnight and am keen to see the allotment and if the emergency bean sowing has worked. I have missed this place. My heart lifts when I arrive. Mary’s bean poles have eager vines on every stick. Her summer plot is saved. OK, tap-rooted thistles are thriving, there is an explosion of weed, many of the peas and broad beans are blown and fallen over, some seed has failed to germinate, but nothing that can’t be fixed by a day or two of hand-hoeing. Suddenly, a flash of rust, a glimpse of white on a scurrying tail as a fox darts across my path. My first sighting this summer. A good omen. Maybe omens are a country-kid thing but maybe also the plot will forgive me for my broken leg and absence. I sow saved red tagetes seed and get to work. A break for breakfast at home, a couple of hours for Sunday papers and back to tidy the potatoes. They are close to cropping now. The chard is heavy-leafed and luxuriant. I hoe every row and re-stake the peas in a downpour. I like giving in to gardening in rain. It closes off the outside, focuses your attention. Just you and the job: a meditation of hand and hoe. A moment of connection. I tie the peas and think of a friend who mails me seed. I send him an eclectic collection, saved and shared from around the world, he sends me Basque peas and intense, small tomatoes because they speak of him and his region. The peas are to be picked young, and sometimes when I eat them I remember Ferran Adrià’s El Bulli, and I remember Lilian.

2011. It is one of the last nights before the closing of the best restaurant in the world. Dom Perignon has flown in 50 guests by private jet: serious wine investors, Silicon Valley billionaires, film stars, their boyfriends, another food writer and me. We are helicoptered into the beach like a scene from Apocalypse Now. We eat 50 small dishes – eggs fashioned from gorgonzola cheese, small, gamy squares of hare, sea cucumber filaments, rose petal wontons and peas. Excited conversation and Dom Perignon ’73 flow. I am sitting at a table of high-powered dignitaries when, deep into the meal, a wave hits me. The room and noise fade a little, a shard of emotion breaks free and I notice my face is wet. I am quietly crying. Ferran Adrià’s peas have burst in my mouth like memories. I’m no longer sitting opposite Roller Girl from Boogie Nights, I am aged maybe six, in shorts and stripy top, on the pink porch of our Devon house. Lilian is there with me, in her yellow patterned summer dress with blue butterfly-wing brooch, sitting, smiling, patiently podding peas into her dented aluminium colander. And as I pick up a pod and help her, I know this is what safety will forever taste like: garden peas freshly picked from the lap of your new mum.

July (#ua04c3f7a-18ec-5f67-a576-61d3400920b9)

The broad beans are almost gone now, just a half dozen or so spring-sown Crimson-Flowering from Mads McKeever at Brown Envelope Seed in Cork. I came across this old variety – and Brown Envelope – early in 2007 with the arrival of the Seed Ambassadors. Andrew Still and his wife Sarah are seed hunters from Oregon, where many obsessive plant breeders are based. Andrew’s passion is for kale, and the pair were on a European tour starting deep in Siberia and ending with Mads on the west coast of Ireland. With Andrew and Sarah came stories. They arrived at the plot on a cold winter morning with packages: from Tim Peters of Peace Seeds, breeder of Gulag Star, a winter salad cross between Russo-Siberian kales and mustards; our first Flashback Calendula. I learned that day of Trail of Tears beans, named from the winter of 1838 when Cherokee were forced from their farms in the Carolinas and marched to Oklahoma in the Indian Territory. First offered through the American Seed Savers Exchange in 1977 by a ‘Cherokee descendent, gardener, seed preservationist, circus owner, and dentist’, Dr John Wyche, the beans can now be shared and bought from heirloom growers. I save the seed and still grow the crops Andrew and Sarah gave us. This year, Trail of Tears have made their way on to a couple of Mary’s poles to supplement the beans that had been struggling to survive.

The pellets and sun have done their work, the wigwam will thrive this time. I weed around the base, careful not to disturb the geraniums Mary has planted there. Elsewhere, there are ominous signs of smothering bindweed breaking through, but Mary has been clearing another small winter bed. I thin out calendula now rampant on both parts of the plot, the flowers sitting brightly by this screen as I write in the early morning. It is glorious high summer, time to garden with a hat and with the sun on your back, time to harvest lettuces, peas and radishes for home, almost time to sow spinach. But the solstice passed a few weeks ago now, the days are warmer but the nights are a little longer. It’s time to begin to plan and plant for winter.

Summer for me is saturated in early memories of Herons Reach, the house on the riverbank that Lilian and Dudley bought to bring up the boys. When I talk of those days, my early life, it is often of ‘the boy’ (or boys) and what happened to him (or them). I rarely use me or we. It might be to do with confusion or creating a protective distance. I notice other people with a similar background do the same. It might be to do with shedding identity, like the ethereal adder skins I used to find in the Aveton Gifford churchyard. It might be about naming. Mum and Dad didn’t like the name Alan, so quickly chose to call me Peter, my middle name, instead. And after a probationary period – I must have passed a test – I was given Drabble (Christopher resisted and stubbornly stuck with Jenkins, a schism between us). Now that we were safe, they thought we could be safely separated.

Scared city child Alan Jenkins was fading, at least for now. Bright-eyed, blond-haired village boy Peter Drabble was cocooning, being born.

As we played, the house too was being expanded, refashioned and renamed. North Efford (north of the ford), a farm labourer’s cottage was metamorphosing into Herons Reach. An extension was added, light was let in, the exterior given a new coat of pink render; rust-red Virginia creeper was trained up its side. That long, happy summer, the first deeply etched into my memory, Dudley waved his phoenix wand, knocking through for French windows, buying the large field behind the house, laying in a drive, the foundations for a lawn, a croft. He planted more trees. Like me, the house was shrugging off its darker past. There was sweet strawberry jam being made in the kitchen, the sound of boys, a cricket bat on ball in the garden, plums and apples were coming in the orchard. Dudley was carving out a home fit for his new family.

While the work was done, we lived in a caravan. It was light, had a breakfast bar and drop-down beds, though we were never inside except to sleep. Christopher would play cricket or football, while I would climb trees and explore the river, catching eels and sticklebacks and putting them in jars until they died.

We had different hair, different eyes, a different smile. He had hazel eyes I almost envied, reddish hair I liked, freckles I wanted, though not the burning in the sun. He was slight while I was heavy, his grin was wider, though mine came more easily.

My favourite photo of Christopher is from that idyllic summer of ’59. He is sitting in the doorway of the caravan with a proud-looking Dudley holding him. Christopher is happy – his tic is slowly disappearing. He is being hugged. He is being loved.

The open smile would slowly disappear. His bright, tumbling chatter would go quiet. He would withdraw back into himself, if not quite yet.

JULY 4. We have fruit on all the tomato plants, about a dozen or so, growing in pots on the roof terrace. Ironic they are there, because it is through tomato seed I found Plot 29. It is July 2006, I am editor of a national newspaper Sunday magazine, juggling million-plus budgets, million-plus readership, 20-plus staff. My day is spent dealing with photographers, writers, agents, celebrities and fashion designers with delicate egos. But all I can think of is how my tomato seedlings are faring when the weather changes. How will they cope with the cold or heat? My next Observer Magazine cover can wait. I am haunted by helpless plants. For the first time in 20 years, my work has a rival. I feel as if I’m needed elsewhere.

I am not alone. There are a few of us on the magazine currently obsessed. We swap small plants and compare their size. We talk of little else.

I have had a roof terrace at home in Kentish Town for years now where I grow flowers and plants in pots. I am married to a modernist architect who likes clean lines, neat rows of seeding grasses and palms. Every year we compromise on a few geraniums – a hangover from my first teenage job in London at a Kensington garden centre. But the haphazard trays of tomatoes are becoming an issue. Where are they all going to go?

It may be only at work that my obsession is understood. The Observer Magazine tomato growers have become competitive. Someone brings their tall seedlings in to show off. We share tomato photographs. And then it hits me: we need a space to grow. Maybe we could sow together, write together, design together, work outside the office. There would be a different dynamic. No one would be the editor, we would create a utopian ideal. We would, I think, grow tomato plants in harmony, like the Diggers or a Sixties collective. I was getting ahead of myself.

We consider guerrilla gardening, transforming urban space. We contact councils to see if they have unused land on a housing estate that would benefit from a few flower and vegetable beds. We ask if there is an empty allotment we could take for a while. Then we find Mary’s sister, Hilary, Camden Council’s allotment officer, and Branch Hill comes into my life.

2006. Ruth is the tenant of Plot 30. She has waited 18 years for an allotment, until one came along when she wasn’t well. It is in north London, near where I live. Hilary says we can garden it for a year and hand it back as a working space. Ruth will hopefully be better by then.

We go to see it.

Ruth’s plot neighbours the one we garden now. My first allotment love, it is hard to make out at the start, not so much overgrown as swamped with weed. It falls quickly away down a steep slope, littered with bindweed, bushes, large abandoned lumps of concrete. This is allotment as waste land. My companions’ faces fall. Mine lights up. Here is territory I have long understood: a garden damsel in distress; beautiful, abandoned, like a rundown river cottage that needs work and a helping hand to express itself.

It starts well. Magazine staff give up weekends to dig. We are seeing ourselves in a different light: muddy, more than a little sweat. But there is too much to do. It will take too long. The weeds are endemic and we are digging out lumps of old buildings lurking malevolently underground. We unearth an Anderson bomb shelter complete with corrugated roof. It is too much to ask. It is their weekend, time to get away from work. Within a few weeks I am on my own, with the rain, the buried bricks, the wire and broken glass for company. Enter Howard and Don and Mary.

I’d first hired Howard to take photographs for Monty Don’s gardening column in the magazine and had loved his work since seeing his book with Derek Jarman on the Prospect Cottage garden in Dungeness. This was austere, artful planting in almost savage harmony with its situation. Howard’s quiet pictures of Jarman, of driftwood and detail, had changed everything for me about how to see space.

Jarman captures him in the book when he writes: ‘Howard Sooley is a giraffe, a giraffe that has stared a long time at a photo of Virginia Woolf; he possesses the calm and sweetness of that miraculous beast.’ From out of this calm – and companionship – together we would conjure our first miraculous plot and go on to make more.

1960. Christopher is obsessed with forming clubs. We have homemade badges, drawn and coloured on card, attached with safety pins. Mum is concerned about the holes in our shirts and jumpers. Our badges are usually round, sometimes shaped like shields. There are arcane rules. He is always the leader. I am the only other member. We are always a secret society because other boys are immune. We never ask girls. We make dens as meeting places. I swear loyalty to the club and Christopher. I am soon replaced by cricket.

SATURDAY JULY 11, 6AM. Under siege. The midges that hang around the pond and plot in the summer evening and early morning are attacking me. I am intent on clearing space for new growth, letting in light and air. It is already monsoony humid, threatening rain. I don’t much notice the midges at first, batting them away absentmindedly, irritated by the odd bite as they penetrate gaps on my shirt sleeves, the pale flash of flesh as I bend. I clear the last of the broad beans, battered by slugs. I pull invading calendula, picking through it for cut flowers for the kitchen table, leaving the vivid orange bloom I haven’t the heart to take. I thin through new-sown salad for lunch. There is much still to do when my face and arms begin to itch uncontrollably, like a child with chicken pox. While I have been working, the bugs have been feasting. I urgently need something to stop the swelling now pressing on one eye, and the raging scratching. I retire from the skirmish, stopping to grab leaves, beans and flowers, and flee.

Later, hopped on antihistamine, smothered in cortisone cream and disfigured with a leer, I return. Howard joins me. We need to sow. The twin pea beds at the bottom of both plots are failing, so we will supplement them with low-growing bush beans. It may be our last chance to sow them this year. We pull the flowering coriander and hang it on a wigwam to dry. I brought the original packet back from Brazil. It is intensely spicy – a local strain, I think. We save the seed for later. I clear another bed for wintering chicories. At the last minute I rip out the top bed too and re-sow with a black bean from Brown Envelope. The crinkled peas should have been picked while we were away. We eat a few from the pod and divide the rest. As the light dips and Howard gets bitten, we finish. In the three hours we have been here we have hardly spoken. The few words exchanged are about the benefits or not of getting a wheelbarrow and which beans are for where. Conversation picks up on the walk home down the hill.

1961. Almost as soon as Christopher and I are reunited we begin to grow apart. Nurture acing nature, if not just yet. He holds on fast to his history and name (though why this decision is his I don’t understand; it should never have been). I pack myself away in search of something safer, smarter, more versatile. Like a Christmas cowboy suit, like dressing up. My identity is broken, soon it will be time to try on Peter Drabble; from underclass to middle class, like the jacket in the first photograph that didn’t yet fit. I often imagine now how my brother’s life would have played out if Lilian and Dudley had called him Christopher Drabble. In my head he is smiling, happily married, with many dogs and kids, maybe managing an arable farm in Canada. His life would have had more choices.

Herons Reach is on the Stakes Road across the mud flats, half a mile from school if the tide is out, a mile if it is in. I love messing on the river on my own, while Christopher loves the village. He is bigger now, brilliant at head-butting me, but I can feel his fragility. Sense the uncertainty. See it when no one else is interested. He will come to rely on his fists. I will rely on my wits.

The change will come between us often. Rural Devon in the Sixties is still remote. A place where brothers have the same names, the same features, the same interests. We are different, and difference is difficult.

Other boys too are to be discouraged, at least at home. In our first year there is a birthday party but this is to be the last. Lilian doesn’t like boys or parties in her house – too noisy, too messy, too muddy, too hard-edged. Softness for me is to be found in other kids’ homes, a warmer welcome with a tender touch. Boys don’t much come around again, not even for Christopher and he collects friends like I collect stamps. He starts spending his days at the farm next door, walking the fields, helping call in the cows, bringing home milk and mud. The farmer is handsome, young, in his twenties, a bachelor, though this thought has only struck me now. I prefer to stick closer to home, closer to Lilian and Dudley, watching as she pares the runner beans he grows into neat piles of wafer-thin green. Food is always simple, almost always freshly grown. For Dudley, as for Mary’s husband Don, runner beans signal English summer.

SUMMER 2007. Ruth’s allotment is slowly taking shape. Howard and I have spent weeks up to our knees, thighs sometimes, trenching out bricks and glass, wire and wood, tree stumps and concrete posts, while Don looks approvingly on. Mary leaves us small bags of salad as encouragement. One day, the allotment association steps in. They hire a skip and I arrive mid-morning to find a fireman’s chain of wheelbarrows to run the rubble up. It seems everyone is here to help.

Sarah turns up from the advertising department of the Guardian where I work. Who knew wellingtons came with high heels? She helps me spread five tonnes of topsoil we’ve brought in to slow the slope. She learns to kill slugs and snails. She drives 300 miles with me to pick up a lorry load of cow manure. ‘Horses’ energy is too fast for vegetables but fine for flowers, you need cow’, was the opaque advice from Jane Scotter. The manure is a gift from a farmer who had answered a plea put out into the biodynamic community. It’s harder than you think to find organic cow muck in London. We drive back delicately in our hired, loaded-down flat-back truck (we have been a bit vague about what we want it for, failing to mention manure). We are barely making it up the hills, laughing, almost choking, in a heavy fug of farmyard.

The slope is tamed now, the soil is fed. We are ready to grow.

The Danish agricultural museum has sent us ‘lost’ seed, including Tagetes Ildkonge (for Christopher), the deepest-red, most velvety marigolds we have ever seen. Sarah and I plant a large bed of perpetual spinach. We have a wigwam of fragrant sweet peas and another of purple-podded Trail of Tears. The tagetes grow to a thick hedge. We have herbs, fennel, flowers, beetroot, carrots, kale, mustards, green manure. I set a national competition for school gardening clubs to design a scarecrow and have the magazine fashion team build and dress the winner. Soon a six-foot scarlet pirate, complete with eye-patch, hat and silvery sword, guards against the resident pigeons. They ignore him. We plant an apple tree, a plum tree, gooseberry and currant bushes – just like Dad. Everything we sow grows lush like rainforest, as though its energy had been imprisoned and is now unleashed. The allotment is happy and so are we, but I can’t bear to thin and throw the weakest tomatoes – maybe I identify with their need, preferring to give them more light and food and love. Soon we have 20 plants, tall and fruiting in the sunniest spot at the top of the plot. We don’t know blight is endemic on the site and that nurturing rain also spreads disease. Their leaves start to brown and buckle. The tomatoes too. Seedlings I have nursed from birth are sickening and dying, and there is nothing I can do. Throughout the site, tomato plants are failing. The weakest die first, of course, their fruits blistered, their stems and leaves discoloured. Seasoned allotment holders strip the leaves and spray them, like a field hospital for failing plants. Still they fail. Like plague before penicillin. In the end we pull them all and cart their corpses to the green bin by the gate. No compost renewal now. A gardening lesson in love and loss. But one I am reluctant to learn.

SUMMER 1973. My first garden in London is in Elgin Avenue, a street of squats near Notting Hill Gate. I am 19, working for a garden centre in Kensington, selling window-box flowers to posh west London ladies. Here, it seems, everyone buys their gardens ready made, no time to wait. This is gardening as competitive sport. I have become skilled at persuading neighbours to upgrade over each other. If one has bought red geraniums and a three-foot window box in terracotta, I’ll sell next door a three-and-a-half-foot in stone and with better, bigger flowers. No one grows from seed. There is a lot of waste. This is new to me. I start carting home pots of dried-out azalea rescued from the bins. Soon I have buckets of rehydrating bushes inside and outside the flat, front and back. I nurture my waifs back to life. As the garden fills up, I start planting out the rest. The speed freaks don’t much mind as long as they don’t have to water. I spread down the street as fast as the dealers spread up. We have azaleas, geraniums, pelargoniums, magnolia, a bay tree slightly bent out of shape. There should be an award for the best-dressed street of squats.

JULY 17. The temperature has been in the high twenties for the past three days and I have promised Mary I’ll water. She is taking a break in Cornwall and I want the plot to look well in time for her return. Howard and I head up before breakfast. I love the light at this time, fruit trees and bushes backlit by the low early sun. Our neighbour Jeffrey is an American banker with a passion for English cottage gardens. His fennel and hollyhocks are two metres tall. Bees stream from the next-door hives like Star Wars fighter squadrons. A fledgling robin, head cocked, watches us. Red amaranth and bull’s blood chard stand in contrast to the other, younger lime-green leaves. All is right in allotment world. Howard waters while I take more calendula, mildew at its base a warning signal of autumn. Time for the borders to breathe, time for beans. Of course we have too many (the seed finally pulled though). Feeler vines outstretch like a drowning man’s hand. Howard is buttoned up against bugs but still they get through. The anxious scratching starts.