По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

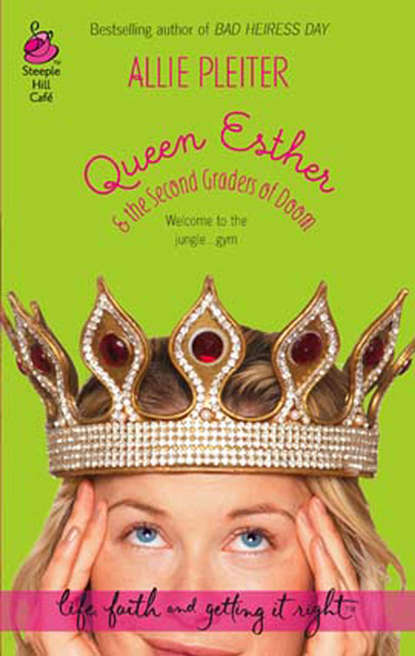

Queen Esther & the Second Graders of Doom

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Essie had long since learned that such a remark was a cue to gush about a child’s outstanding class behavior. Anything else would be viewed as a deficiency in one’s teaching skills. In her high school career, this remark—or anything close to it—was a parental “weather balloon.” Something lofted by a parent to see if Essie was up to the challenge of their brilliant but slightly misunderstood progeny. Evidently, it was no different with the younger set.

Taking a sip of coffee, Essie did what was expected. She launched an enthusiastic rendition of Stanton’s admirable qualities, concluding with, “Those papers you sent over didn’t surprise me one bit.” Okay, not exactly the truth—it floored her that Dahlia’d done what she did—but it was optimistic. Sort of.

They played this verbal game for the next twenty minutes, taking turns identifying Stanton’s strengths and talents. Here and there each of them cited the lengthy paper, using the data as the springboard to a compliment. It was a taxing, almost choreographed conversation. Essie was used to it, but mostly involving the complexities and large-scale behaviors of teenagers. Trying to make the case for Stanton’s often-violent obsession with being first in line as a precursor to leadership skills, well, that took a little more verbal agility. It was always a precarious knife edge on which to balance a conversation; when to be direct, when to hint at a problem, when to tell the parent what they wanted to hear. Essie was exhausted by the end of her third cup of admittedly excellent decaf. Come on, Josh, wake up and give me a diaper change to catch my breath here.

“What does the class need, in your opinion?”

Sedatives, Essie thought before she could stop it. Instead, she attempted a braver course. “In all honesty,” Essie ventured, “another set of hands would make things much easier.”

Dahlia didn’t even recognize the veiled request for her time. “Well, yes, of course,” she said, as though it were obvious that it should be someone’s—but clearly someone else’s—job to take care of such details. “It’s church policy to have two teachers. I’m sorry your co-teacher moved on such short notice and we’ve not yet found a replacement. I was thinking, though, more in the way of equipment, materials, that sort of thing.” In other words, what can I buy you? Because I have no intention of coming in there and helping you myself. Nope, no surprises here. “I am very busy with coordinating the Celebration, of course, but I do want to do my part in helping out the class.”

No, you don’t, thought Essie, you want me to give you an out. “I know it’s a lot to ask, but do you think Carmen could whip up some of these goodies for the Harvest of Witnesses event in a few weeks?”

Bingo. She’d hit the target. Dahlia fairly beamed. “Why, of course. Something a tad more nutritious, of course, but goodies nonetheless.”

“That’d be great. And I know we need someone to make up little baskets—nothing too girly, but still creative—for the class to use that day.” The children had an event where they went around the church “harvesting” goodies and information about great figures of the church. A few years ago, at Mark-o’s suggestion, a group of moms had created this event—a combination of scavenger hunting and gift-giving on the first day of November. It had become one of the things the church was known for, one of those things that drew new families to the church. Essie had always considered it one of the coolest things her pastor brother had ever done. “Can you think of someone who’s got those kind of talents?”

Dahlia’s pen bobbed again. “Oh, I’ve just the person. Vicki Faber—Alex’s new stepmother? She has a decorating business. She’s redone the house beautifully. I’m sure she’s got someone who could whip together just what you need.”

Alex Faber’s stepmother. Icky Vicki. Vicki and Alex’s dad had been one of the class’s invisible sets of parents. Alex’s older sister Sharon—the one who’d come up with the “Icky Vicki” moniker—always collected Alex from class.

“Here’re her numbers, why don’t you ring her up?” Dahlia said, handing her a thick card with the heading “From the desk of Dahlia H. Mannington” across the top. Pouring more coffee, her voice took on an “I don’t mean to be unkind” tone. “She is a bit younger than you, but I do think you might enjoy getting to know each other.”

I’ll just bet she’s “a bit” younger than me, Essie’s thoughts replied. And probably looks like she walked off the set of Baywatch. What am I doing with these people?

“I think Vicki has had difficulty adjusting to her new role. It was a nasty divorce, really. Vicki’s had her hands full trying to smooth things over. I imagine she’d welcome a little project to do for the class— I’m sure she knows loads of designers who could whip up a dozen or so perfectly manly baskets. I’d try the cell phone number first—Vicki is out and about most of the time.”

“Thanks, I’ll call her.”

Dahlia closed her organizer and notepad. Again on perfect cue, Carmen appeared in the French doors with a small white bakery box. “I had Carmen pack up a few of these rolls for you to take home. They’re far too good for me to keep in the house without gaining a dozen pounds, and I wonder if that husband of yours can help finish them off?”

Dahlia Mannington did think of everything.

“Oh, Doug will be more than happy to have these. That’s really nice of you.” And, believe it or not, she meant it.

Chapter 7

And on Some Sunday Afternoons…

“I’d never eat fish for lunch. Yuck.” Decker made a face as the Doom Room pondered the Bible story of the loaves and the fishes.

“Not even fish sticks?” Essie ventured. She fondly remembered the special days of fish stick and French fry frozen dinners on folding trays in front of the television. They were one of the great treats of childhood to her. She and Mark-o would usually have a competition of sorts as to who could glob more ketchup on a fish stick. Essie usually won.

“Fish sticks are gross,” Decker replied. “Besides, Mom says they’re fattening. She makes me eat Sam Man—you know, the pink fish—every Tuesday for dinner, but I hide it in my napkin and give it to Sparky. What’s ‘brain food’ anyway? I’m not eating that Sam Man’s brains, am I?”

Essie guessed that either Decker’s dog or cat was eating very well on Tuesdays lately. Salmon versus fish sticks. It sounded like a bad country song—

I’m just a fish stick gal,

Caught in a salmon fillet world…

“Salmon, Decker, is a fish, you’re right. But, no, it’s not brains. It’s good for your brain like lots of other kinds of protein—those are the types of foods that give your brain the energy it needs to do its job.”

“I think better eating cookies,” Dexter proclaimed, clearly unswayed.

Essie dragged the discussion back to the topic at hand. “Well, then, it’s a good thing you’ve all had a cookie or two, because we have lots of thinking to do today.” She clasped her hands. “Now, we’ve already read the story about this boy and how he brought his bread and fish to Jesus.” Decker opened his mouth, presumably to start up again about the grossness of fish for lunch, but Essie held up a silencing finger. “Almost everyone’s dad was a fisherman there, so bread and fish would have been like…like peanut butter and jelly to us. Everybody ate it.”

“I’m yullergic to peanut products,” pronounced Peter with a resigned voice. Just as Essie knew he would. Peter, it seemed, was “yullergic” to just about everything. Some days all Peter could add to a conversation was a list of relevant items to which he was allergic. On those days he would sigh, speak without enthusiasm and generally look as if the entire world was gunning for his immune system. How he reconciled such an outlook with his love of bugs and other slimy creatures, she couldn’t really say. An image of Peter, foraging under a rock with latex gloves on, flashed uninvited in her brain. Focus, Essie, focus.

“Okay,” she continued, “what he ate isn’t really the point here. The point is that he gave what he had for Jesus to use, even though it didn’t seem like much at the time. “David,” Essie said, turning to Cece’s son in an attempt to get things on the right track, “do you think five loaves and two fishes is enough to feed thousands of people?”

David scrunched up his forehead in thought. “You’d have to break it into really tiny pieces.”

Essie had to laugh at that one. “Even then, what that boy had just wasn’t enough to go around. Remember, it said that there were baskets of leftovers even after everyone had eaten. That’s why it was a miracle. Jesus took that food and made it able to do something very special. Something only God could make happen.” She looked around the room, trying to catch each boy’s eyes. “Sometimes the stuff we have to do in life feels like more than we can handle. Like we don’t have what it will take to do what needs to be done. Does anyone have an example?”

Justin’s arm shot in the air. “My baby sister. Sometimes she cries so much, I think I’m gonna explode.”

Essie thought about Josh’s most recent teething episode and could only nod in sympathy. “Babies are a handful, aren’t they?”

“I heard Mom telling Dad she thought she’d never, ever get to sleep again. When I told Dad we ought to make baby Megan sleep in the garage, he told me not to say that in front of Mom, but he was smiling when he said it, so I know he thinks we oughta try it.”

Essie could only imagine.

“My dad has a new job this month, and it’s making him really nervous,” offered Steven Bendenfogle. “He gets grumpy a lot. And sometimes he doesn’t come home till way after my bedtime. And he brings home lots of homework, besides. I think he feels like it’s too hard.”

“New jobs feel too hard lots of times. You could really help cheer him up, Steven.”

“I don’t know.” Steven shook his head. “He’s really grumpy some nights.”

“Well, now you’ve got something that feels too hard now, too, don’t you? It feels like it may be too hard to cheer up someone who’s really grumpy, doesn’t it? That’ll take Jesus’ help, too.”

Steven thought about that for a while, but then nodded.

“It’d be too hard,” said Stanton loudly, “to beat Jesus in a jumping contest, ’cuz He’s God and He’s got superpowers and stuff. He’d beat you at anything!”

Well now, superpower was an odd definition of deity, but it must have rung true to the average eight-year-old, because the other boys all immediately agreed. Instantly, boys began shouting examples such as “I bet He could spit a watermelon seed around the world,” or “He could kick a soccer ball through a brick wall,” and even several instances of X-ray vision.

“Or,” interjected Essie in a voice loud enough to cut through the din, “transform one little boy’s lunch into enough food to feed thousands of hungry people.”

Everyone had to think about that for a moment. Then, very quietly, Stanton said, “Yeah. Cool.”

Was it okay to think of Jesus’ miracles as superpowers? She hoped God didn’t mind a little creativity, because clearly Jesus just went up a couple of notches in the “cool” department for a few of these boys. And that was the whole point, wasn’t it?

“Superpowers aren’t real,” she said, because she felt it ought to be said. “But Jesus, and the things He can do with us when we believe in Him, those are real. And yeah, Stanton, they are cool. The older you get, the more you believe, the cooler it gets.” Nods and a few amazed faces.

Zing. It sunk in. Score one for the crazy mom from New Jersey.

And the very cool God who brought her here.