По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

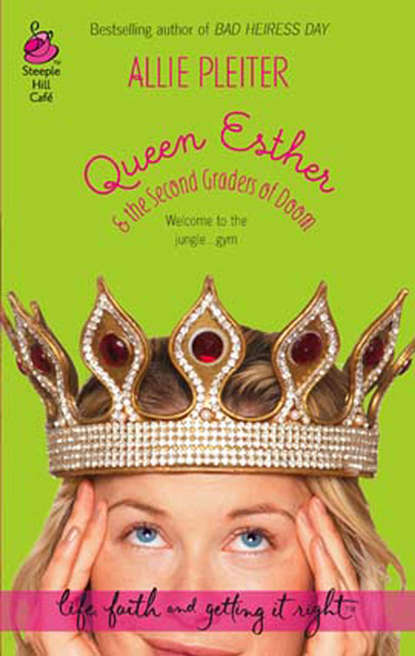

Queen Esther & the Second Graders of Doom

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“He spent ten minutes telling Dr. Einhart how he exercises each day.”

“Mom! That couldn’t be further from the truth. Why did you let him do that?”

Essie’s mom blinked. “Do what?”

“Lie to his doctor? It’s ridiculous.”

“But he’s supposed to walk each day. They’ve told him he should walk each day.”

Essie shot out a frustrated sigh. “Well, he doesn’t, does he? We both know he doesn’t.”

“Well, of course he doesn’t. His knees bother him.”

“Mom, we’ve been over this a gazillion times. If he’d walk more, his knees wouldn’t bother him, then he’d drop some of that weight, then his knees would bother him less. It’s just going to get worse if he keeps sitting there. No, no, it’s not just that, but sitting there and lying to his doctor.”

Mom crossed her arms. “I’m not going to make him look bad in front of his doctor.”

Essie wanted to scream. “This is not a popularity contest, this is Dad and his doctor. What’s the point of going to a doctor if you don’t actually tell him what’s going on?”

“How’s Doug, dear?” Mom clipped that thread of conversation clean off. It was quite clear no further discussion on the subject of honesty with one’s doctors would be allowed. Essie fought the urge to go find her father and shake him by the shoulders. Lord, help me. They sure won’t help themselves. Patience, just send gallons and gallons of patience. Right this minute, or I’m going to go out of my mind.

Essie let out a long, slow exhale, rolling her shoulders back as she watched Joshua inspect his thumb. “Doug’s doing fine. The new department has more people and more resources than he had in Jersey, so he’s happy. It’s been a good move for him.”

“That’s nice, dear. Have you talked about having another child? Soon?”

Essie popped her eyes wide open. “Mom, Josh is five months old!”

“I had you and Mark only a year apart. You played so well together.”

Oh, yes, Mom, I have such happy memories of tearing Mark-o apart in joyful siblinghood. Not to mention I’d like to get acquainted with the sight of my toes again.

“Really, Mom, it’s a bit early for that sort of thing.”

“Nonsense. You’re thirty-one. Life won’t go on forever you know. An old woman can pine for grandchildren, can’t she?”

Essie didn’t quite know how to convince her mother she didn’t want to be pregnant for every waking moment of her thirties. Deflect the attention. “You know, there’s always Mark-o. He could have children. He’s married, you know. Married people do that sort of thing.”

Her mother waved a hand as if that were an absurd suggestion. “Oh, yes, but Mark is so very busy with that church. And Peggy—well, I just don’t see Peggy being ready to have children soon. She’s just not that motherly type.”

So I should pop out a gaggle of grandchildren to compensate? And aren’t Doug and I busy? Now that I’m at home with Joshua, is procreation my only purpose in life?

“You, my little Queen Esther.” Essie watched her mother burst into a wide smile. “You were always meant to be a mother. I always knew you’d give me precious, beautiful grandbabies to love.” She scooped up Joshua just as he was dozing off, and made loud snuggly noises into his neck.

Which, of course, sent him into a full-fledged wail.

“I just never thought I’d see the day my Essie fed her children silverware.” Her disapproval of the now-revered grapefruit spoon trick was almost palpable. “Really. No wonder he cries so much.”

He cries so much because you just did the unthinkable: you woke a sleeping baby. A sleeping cranky baby. My sleeping cranky baby that almost never sleeps. Mother-r-r…

“How can such a darling boy be so miserable?” Dorothy made a sour face and handed her “precious grandbaby” back to Essie, obviously unwilling to hold anything making that much noise, even if it was flesh of her flesh.

“He’s teething, Mom. Don’t you remember how miserable a toothache is?” Essie fished around on the couch for the spoon, mentally convincing herself it didn’t need reboiling just because it had endured forty-five seconds on her mother’s couch cushions. She returned it to Joshua’s gaping mouth.

Within fifteen seconds Mount Joshua ceased to erupt. With a dying chorus of wet gurgles, Josh settled into a slow, relieved chew. Essie felt the spoon’s handle wobble up and down as Josh’s besieged gums found their solace. “I know it’s weird,” Essie replied to her mother’s subsequent frown. “But it works. See? It works. I don’t care how, I don’t care why, I just know it works. If putting him in purple socks worked, I’d probably do that, too.”

The front door pushed open and Essie’s dad shuffled in, clutching a white paper pharmacy bag. Mark-o entered behind him, holding a paper bag of groceries. It took Bob Taylor four full minutes to make it from the front door to his permanent spot on the recliner beside the couch. He grunted with every step, and groused with every breath about “those knuckleheaded quacks and their useless pills.”

“I’m gonna spend my pension at that pharmacy,” he grumbled as he eased his large frame into the worn chair. “Every day and every dollar’s gonna buy some drug executive a shiny new yacht.”

“Now, Pop—” Mark-o had put on his counseling persona; Essie could tell by his voice. “If it weren’t for those useless pills, you’d be in the hospital looking at a shiny new wheelchair.”

“Baloney.” Essie’s dad tossed the bag on the coffee table in disgust. “I’m slow, but I’m still moving. Since when is it a sin to get old and slow?”

“At your young years,” Mark shot back, his fraying patience beginning to show through the practiced calm, “it’s a sin.”

“So’s lying.” The words jumped out of Essie’s sleep-deprived mouth before she could think better of it. “As in lying to your doctor.”

“Oh, honey…” began her mother.

“Pop, all she’s…”

Pop’s next booming question stopped the argument in its tracks: “What on earth is that in my grandson’s mouth?”

“Now, who knows the story of Jonah?”

Four cookie-crumbed hands shot up. Essie passed out a second set of napkins before she allowed Justin to answer.

“He got stuck inside a fish.”

Essie smiled. “He sure did. You were listening in assembly this morning, Justin. Who knows how he got there?”

Stanton, a tall boy in pressed pants and gelled hair, strained to get his hand as high as possible. He yipped a series of small “Me! Me! Me!” s. Frantic to be picked, he seemed oblivious to the fact that his was the only hand aloft.

“Stanton?”

“I bet he was swimming. My dad, he took us swimming once, on vacation, and I was really worried about the fishes when we were swimming. I didn’t want to swim where the fishes were, but he told me pools don’t have fishes,’ specially hotel pools. And we were in a hotel ’cuz we were on vacation and stuff, ’cuz we went on vacation over Christmas and we got to go somewhere warm so we could go swimming, but my big brother got in trouble ’cuz he…” The entire speech whooshed out of him in a single breath.

“Okay,” Essie cut in, placing her hand on Stanton’s arm. The boy was wearing a watch. A fancy one. Who buys designer watches for their eight-year-old? Dahlia Mannington, of course. For all his dapper duds, Stanton was a sweet boy with tender green eyes and a near insatiable appetite for attention.

“Swimming is fun. But Jonah wasn’t swimming for fun. Can anyone tell me why Jonah was in the water?”

“It’s hot where he lives!” said Decker Maxwell, as he tipped his chair back far enough to send himself head over heels. The resulting laughter stopped any hope of education dead in its tracks for the next five minutes, as all the other boys tried immediately to follow suit. Essie finally had to resume her lesson on the floor in a circle, without the benefit of chairs. She tried to ignore the sensation of her legs falling asleep as she patiently suggested that Jonah was running from God’s commands.

“Did Jonah get a time-out? I wanna do my time-outs in whale guts!” Peter, a smaller boy with wildly curly hair and an obsession with all things bug-and animal-related, pushed his glasses back up on his face as he joined the conversation.

“Well,” replied Essie, catching a pencil as Stanton sent it through the air in another boy’s direction, “it was sort of a time-out. In one way, God saved Jonah because he wouldn’t have survived being thrown out into the middle of the ocean like that. But in another way, God gave Jonah a good long time to think about what he’d done.”

“My mom does that,” grumbled Peter. “In my ‘Think It Over Chair.’” He crossed his arms over his chest in an exaggerated fashion that made his next comment almost unnecessary. “I hate my Think It Over Chair.”