По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

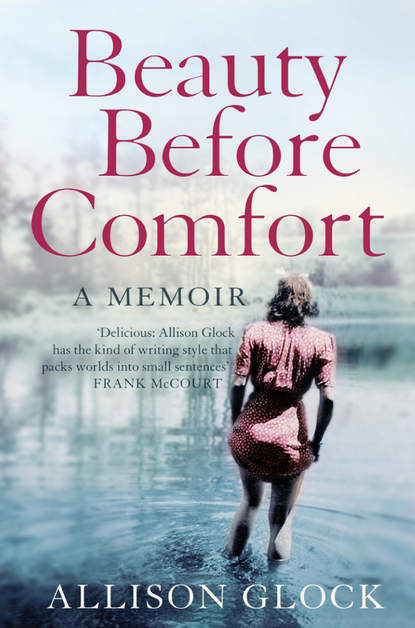

Beauty Before Comfort: A Memoir

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Beauty before comfort,” she would say as she trimmed her brows and cinched her belts corset-tight. My grandmother is so beautiful that she has never once been comfortable, a cross she bears with the subtlety of Liberace. Even now, at the age of eighty-one, she has her hair colored weekly and doesn’t descend the stairs without full makeup. If an opera spontaneously broke out at her nursing home, Grandmother would be appropriately dressed.

It is a legacy she has passed down to her own daughters, and they to theirs. Generations of women painting themselves to perfection, ramming their feet into tiny shoes, sucking in their bellies, dousing their hair with enough spray to gag a horse, girl after girl learning the value of being “as pretty as you can be.”

As family legacies go, beauty before comfort is a particularly cumbersome inheritance. For my mother, it necessitates a minimum full hour of prep time every morning, time that lengthens as she grows older. For my youngest sister, it requires an arsenal of beauty products—enough to fill a second suitcase when she travels. For me, it meant coming to terms with the fact that in a long line of great beauties, I was not a great beauty, and that I’d better start honing my sense of humor.

For all of us, it means living with a low-grade anxiety, a murmur in our brains fueled by our collective self-consciousness and our compulsive sizing up of our place in any room—Who’s prettier? Who am I prettier than?—as if our very survival depends on our ability to seduce.

For Grandmother, the pursuit of beauty meant something deeper. Born as she was in a factory town, tiny and blinkered and perched precariously on the banks of the Ohio River, beauty meant nothing less than freedom. Ugly girls didn’t escape to Hollywood and sit by the pool in leather mules. Ugly girls didn’t marry up and fly away on airplanes. Ugly girls got left behind and never knew any better.

Grandmother believed that there are people who tell stories and people who inspire the telling, and she intended to be the latter. “A pig’s ass is pork,” she would say when the local men pecked after her, wanting to know her heart’s intentions. Or maybe, “It ain’t lying if it’s true.” When the boys would confess their desires, daisies in trembling hand, Grandmother would smile and weave the flowers into a halo for her hair. Before it was all over, she would have seven marriage proposals and a body like Miss America and her share of the tragedies that befall small-town girls with bushels of suitors and bodies like Miss America, girls who dare to see past the dusty perimeters of their lives.

She keeps a memory book from this time, her youth, before she was tired and widowed and old, when she was cream-fresh and believed her life was as open as the road. All women kept scrapbooks back then, hoping somehow that their history would mean more than most. My grandmother’s is a three-ring brown plastic binder with black construction-paper pages holed out at the edges and snapped inside. The pages have worn through the years and many have Scotch tape bonded to the seams. In the book are newspaper clippings and birth announcements, ticket stubs and good-natured platitudes cribbed from local papers, bromides along the lines of “Though you have but little or a lot to give, all that God considers is how you live.” (I can only figure she found these snippets ironic, as my grandmother has never shown the least bit of interest in God or any of his considerations.)

For the most part, there are photographs. Black-and-white images of her and her boyfriends, sitting on cars, standing on fences, the men smoking cigarettes in World War II uniforms, Grandmother fanning out her dresses to best advantage. On many of the shots of the men, there are love notes penned in the corners, hungry scrawlings declaring their affection for the girl behind the camera.

There must be more than one hundred of these pictures, I know because Grandmother and I have often looked at them. Every Christmas or Fourth of July, out comes the memory book and the stories.

“Now, that boy sent me a big bottle of Chanel Number Five from boot camp, I saved the bottle. And that boy took me to the Kentucky Derby; I had a mint julep. And that boy raised greenhouse roses. And that boy took me roller-skating. And that boy died in the war.”

She tells me which boys she loved and which loved her. She tells me about her brothers and her sister and her mother and father. She tells me about her house and what went on there and how it was to be young in West Virginia, to be a skinny, eager child with disobedient hair and bottomless longing. Certain pictures are like songs, making her cry no matter how many times she sees them. Almost every snapshot is labeled neatly with the subject’s name—including each photograph of my grandmother: “Aneita Jean Blair” tightly jotted in the white border at the top, a nod to the future she dreamed she’d have, one where strangers knowing who she was would matter.

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_d1e4983f-4a42-5684-99aa-47076756e2f5)

The state of West Virginia was born in conflict and has retained lo these many years a mulish attitude problem. The people born there are chippy. It’s a birthright.

The state came to be in an act of war, when the western half of the state broke off from its eastern parent, Virginia, in 1863. The two sides disliked each other with familial intensity. The western half envied the wealthy eastern half. The eastern half was ashamed of the western half. The westerners saw the easterners as idle slave owners. The easterners saw the westerners as boorish rednecks.

“What real share insofar as the mind is concerned could the peasantry of the west be supposed to take in the affairs of the state?” said easterner senator Benjamin Watkins Leigh on the floor of the 1829 Virginia legislature.

“Screw you,” said the peasantry of the west.

Western Virginians were sick of the ridicule, of being overlooked when it came to building schools, of being dismissed as “woolcaps” by the richies who lived in the pampered south of the state. Then, around 1850, the state of Virginia borrowed $50 million for improvements and the construction of roads, canals, and railways. The only money spent in what would become West Virginia was $25,000to build the “Lunatic Asylum West of the Allegheny.”

It was not a promising precedent, and the two regions formally went at each other’s throats. The rivalry played out in the legislature for years, until finally President Lincoln stepped in and pressured Congress to push Western Virginia’s independence through. This decision “turns so much slave soil to free,” he said. It was “a certain and irrevocable encroachment upon the cause of the rebellion.”

Thus was born a state and the lasting tradition among its people of giving whomever they please the finger. “Mountaineers are always free,” declares the state motto. This history was not lost on my grandmother.

Aneita Jean Blair was born at the foot of her mother’s bed on September 30, 1920.

“I was born ugly,” my grandmother says. This is a lie, but it is a lie she believes.

In the album, there is only one photograph of the infant Aneita Jean. It was taken on the Fourth of July and she is roosting on her father’s knee, a lump in white cotton, with a black wick of hair falling down her forehead. Beside her, her two-year-old brother, Petey Dink, rests an American flag on his shoulder, his free arm raised to shield his eyes from the sun. A horse and buggy is parked behind them. It is impossible to tell if she was in fact ugly, but, given the gene pool, it seems unlikely.

On the day my grandmother entered the world, it was storming, and because her mother always kept the windows open, Aneita Jean Blair was not only ugly but in the rain. When her father rushed into the bedroom, Grandmother was already there, pinned down by her mother’s foot, wailing and kicking in a runnel of wet. It is because of this that she says she is crazy.

“I’m crazy, you know,” she’ll tell you soon after you meet her. She is indiscreet. She tells the grocery clerk she’s crazy, the bank teller, the librarian. She once met a boyfriend of mine, grabbed his arm, told him she was crazy, then suggested the two of them climb into a dog crate and “see what happens.”

Aneita Jean weighed seven pounds at birth, a weight she would more or less carry until the first grade. She was a colicky baby, a crier. She spent the first years of her life in a foul mood, believing even then that a life without beauty is a pile of slop.

In a photo of her as a toddler, Aneita Jean is standing outside, her mouth screwed into a knot of agony, her hair sticking up like a pitched tent. When she was two, her older brother, Petey, had given her a doll that frowned, which made everyone laugh, but which she despised and pinched when no one was looking.

“Everybody thought it was funny,” she says. “I didn’t think it was so damn funny.” And then: “Buster Keaton never smiled, either, and everybody was mad for him. Ah, horseshit feathers.”

In public, Aneita Jean would stand eyes forward, lips flattened, hair chopped close to her neck, reeking of defiance and looking lifetimes older than the little girls next to her, with their eager smiles and shy eyes. Family lore has it that it would be a full three years before she ever smiled. Three years, never so much as revealing a tooth.

I’m going to leave here one day,” she’d say to her mother years later, her head nestled in her lap.

“Why would you go and do a thing like that?”

“Because.”

It wasn’t much of an answer, but then, as a little girl, she hadn’t really thought it out. It was an instinct. She was going to leave, become a painter or a singer; she was going to wear dresses with sequins and make art and meet dark men in suits who smoked pipes and nodded their heads in approval.

“No one leaves here, Jeannie,” her mother, Edna, would chide, tucking a curl of hair behind her daughter’s ear. Edna herself had moved only twice, arriving at the new spot within a few hours of the last.

That few people escaped West Virginia was true, but an irrelevancy to Aneita Jean. Ugly or not, she decided that by the time she was sixteen, she’d find a man who would carry her over the mountains to a place where all the women lolled about, resplendent in chiffon and diamonds, and all the men looked like Errol Flynn before he started drinking so much. Someplace glamorous. Like Pittsburgh.

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_a3a18ece-756e-5345-bf1c-72c7b1dc4807)

“I couldn’t stand the dirt. The alleys. The ignorance. You know how you drive through towns and wonder, Why would anyone live here? That’s how I felt. But we lived there. We lived there our whole dingdong lives.”

Aneita Jean Blair was the second child born to Edna Virginia McHenry Blair and Andrew Charles Blair. Edna was a natural flirt. She was Irish, bosomy, and spirited, with jowly cheeks that vibrated when she laughed. Andrew, a Scotsman, was not a jovial person and seemed in a constant state of mystification as to how he’d ended up married to one.

The year my grandmother was born, West Virginia was in the throes of a moonshining epidemic. Every month, more forbidden stills were discovered, and in a raid just weeks before Aneita Jean’s birth, state officials found a still in a nearby church, news that sent Edna into hysterical laughter. Andrew didn’t cotton to irony, so a month later, when the Ceramic Theater showed The Family Honor, “a picture that sharply contrasts right thinking and right living with false pride and evil deeds,” Andrew Blair made sure his wife saw the show.

Andrew and Edna would have five kids altogether, all spaced roughly two years apart. The first was Andrew junior, whom everyone called Petey Dink, then Aneita Jean, then Forbes, followed by Alan, and, finally, Nancy. The Blairs were an attractive family, but Petey Dink and Aneita Jean were dealt the best genetic hand. Both were tall and lean, with wide eyes that jumped off their pale round faces. Both had small plump mouths, and with their translucent skin and golden red hair, they looked every inch like their Celtic forebears.

Forbes was a blonder, blander version of Petey, more like his father, sturdy and tense, while Alan and Nancy were born with brown curls and longer faces. They looked like mournful cherubs, and they studied intently while Petey and Aneita Jean robbed apple orchards, their laughter trailing behind them like a kite.

They all lived in a brown brick and clapboard Victorian at the corner of 917 Phoenix Avenue, in Chester, West Virginia, just on the cusp of the good neighborhood, where the people didn’t have to stretch sugar or send their kids to the government depot for cans. Just a few blocks away, they could wade into the woods and play amid the dogwoods, rhododendron, wild violets, and long, wispy trees that rustled like bamboo.

Their town was known for two things—pottery factories and not being as pitiable as its downriver neighbor, Newell.

Pity being a relative thing in West Virginia, the distinction boiled down to small details. Newellies still kept chickens in their yards. In Chester, there were fewer chickens and more flower beds, and on occasion, in the nicer homes, wallpaper.

The Blairs had flower beds and hand-sewn curtains cut from heavy cotton bark cloth printed with tropical leaves. They had a porch and a walled yard and a stairwell up the center of the house. There were four bedrooms and one bath. The street out front was gray brick, and in either direction there was a view of the factory smokestacks.

Like Newell, Chester was a blip on the east bank of the Ohio River, part of a cluster of small towns that make up the panhandle, Hancock County, a region of steel and brick, but mostly clay. The clay was unique. Plentiful and unusually malleable, it was perfect for making crocks, jugs, stoneware, and china.

Potters lived there, whole generations of them, growing up in cramped company houses, knowing only the job they were trained to do and the folks around them. Starting as early as 1830, people moved to what is now Hancock County, discovered the clay, became potters, and stayed. It was a marriage of resource and craftsman, and it was a marriage for life. “The second-oldest profession,” they called it.

The clay along the Ohio River had a blue tint and smelled of standing water. Once in your nose, the scent never left, just dug deeper into your pores, so each breath reminded you where you were. It was persistent in other ways, digging into fabrics and under fingernails, like white blood, thick and seeping, growing crusty when it dried. Most potters didn’t even bother trying to eradicate the clay; there was always more carried in their pant cuffs, in their hair, on their toothbrushes. Andrew Blair was a potter. And when his sons grew old enough, they, too, served their time in the factories, until the war called them away to more epic fates.

Throughout Aneita Jean’s life, the Blair family was well known in the valley. The family’s combined good looks and social acumen made them easy to spot. Forbes was an usher at the theater. Petey Dink danced with all the ladies, and danced so well that even the wives among them never refused. The whole family, save Edna, was dapper, but even she transcended her plain frocks aided by her round biscuit cheeks and knowing black eyes. Her husband favored layers of starch, stiff shirts and vests and jackets, so crisp and pointy, he looked to be cut out of cardboard.

In one family picture, Petey, fifteen, wears a floral-print necktie with a rumpled dress shirt and high-waisted pants. Aneita Jean, thirteen, wears a pleated skirt and wide-collared shirt. Forbie, eleven, aping his father, looks strangely adult in a herringbone suit, while Alan, nine, and Nancy, seven, sport fitted sweaters and stovepipe pants. Together, they seem to sing from the page, the clothes incidental trappings rustling around their collective confidence; except Alan.

Alan Blair had the misfortune of being born agreeable in a family of severe stoics and manic charmers. He was neither the oldest boy nor the youngest child. He was not the handsomest or the smartest or the cruelest. He was not a jock, a scholar, or a delinquent. He was just good old Alan Mead, shy and curly-headed, and he kept low to the ground and quiet. (Later, he would become an elementary school science teacher who rarely mentioned how he had piloted a drone plane through the mushroom cloud of the first dummy atomic bomb test, or how, as a full commander in the war, he had nearly died in a hurricane off the coast of Japan when his plane pitched into the ocean like a javelin.)