По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

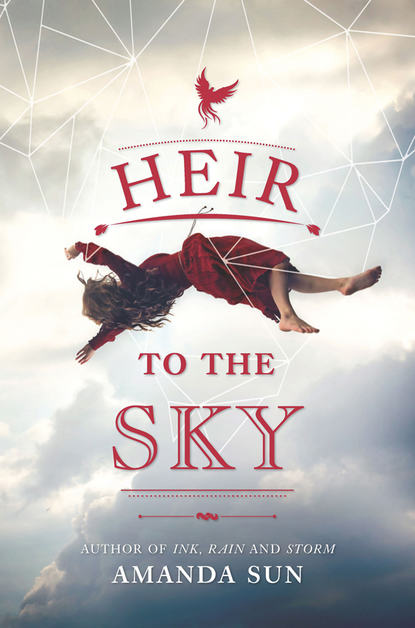

Heir To The Sky

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

TWENTY-ONE (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-TWO (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-THREE (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-FOUR (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-FIVE (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-SIX (#litres_trial_promo)

TWENTY-SEVEN (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

ONE (#u68519163-1522-5c1c-88d0-91f1246faa74)

THE ROCK BRIDGE is the most dangerous part of the climb, and so I lower myself to my hands and knees to crawl along it. On either side of the sparse grass, the layers of slippery rock spread out like frail wings of stone. They look like they will support my weight, but I know a single step on them and they’ll crumble, tumbling toward the earth far below Ashra, falling endlessly until they disappear from sight.

I used to throw flower petals over the edge of this floating continent to see how long I could track them, to see how far the fall really was, down to the mossy green and blue blurs of the world below. The blossoms would float on the wind, tumbling round and sometimes blowing back onto the outcrop, clinging to the silvery stone as if they, too, were afraid of falling.

I take another step, cursing these slippery red shoes on my feet. There’s no fence out here like there is around the village of Ulan. There’s no reason for one. No one ever comes out this far, past the borders of Ulan and the farmlands, past the citadel and the landing pitch and the great white statue of the Phoenix, May She Rise Anew. This part of Ashra is too rocky to develop or inhabit, too sheer and dangerous to trespass like much of the continent to the northwest and the east. And so it is its own lonely wall, one that keeps out the masses and invites solitude.

The soft sole of my right shoe scrapes against the bare grass that clings to the edge of the outcrop, and I stumble forward, my fingertips clinging to the jagged rocks. The wind tangles in my hair as I look up. A bird is soaring alongside the edge of rock; some kind of gull, I think. His white wings are outstretched as he easily rides the current, dipping and diving gently as his head tilts, and his beady eye stares at me.

“Don’t worry.” I laugh at him. “I can make it.” I pull myself onto the outcrop one arm after another. My shoe finds traction again, and I heave myself up onto the soft, rich grass, the danger of the rock bridge finally past.

I take a breath and stand, brushing the gray dust from my scarlet robe, the golden tassels of my rope belt swaying in the wind.

A clearing of emerald green spreads out to the edge of the continent, a flowery field bursting with rich and vibrant color clinging so close to the edge. The fireweed blazes purple and red, the poppies burn with searing blue and fiery orange pistils. It’s why I climb up here, why I risk everything to be here. It’s a floating luminous realm for one.

The gull caws into the gust of wind as I step toward the edge. If I reach out, I could touch his outspread wing. Instead I look down past the tips of my shoes, past the sheer edge of Ashra. The view down to the earth is dizzying. It looks like a world of mottled green and blue, what little I can see of it. The clouds blot out most of the view as always, leaving the earth a mystery.

It’s hard to believe we ever lived down there, trolling the dregs of that land like the bottom of a dark ocean. But the annals say we did, those dusty leather-bound tomes in the citadel library that almost no one reads but me. No one wants to remember; it’s too painful to think of what we’ve lost.

Oceans are another piece of earth knowledge left over in the annals. We have a deep, cold lake on Ashra—Lake Agur—that during the season of rains spills over the edge of our floating island in a thin waterfall of azure and foam tumbling toward the earth. The current is dangerous, and the citizens of Ulan are forbidden from swimming in it, but we all do anyway, in the southern swell where the current is weak and the waterfall is far away. Streams flow into the river like veins into a heart from all across the continent.

Ashra is a small island, compared to the earth stretching below that doesn’t seem to have an edge to it. Our home in the sky is maybe three days’ walk from edge to edge, longer than it is wide, but no one bothers to go past the farmlands, and the farthest I’ve been allowed is to camp in the northern outlands with Elisha. My father would notice if I went farther, although one of these days I might just slip away and traverse it anyway.

Lake Agur is a closer option for a quick day of youthful rebellion, but you can always see the borders of the sparkling expanse, and the world around you never grows very dark when you swim to the bottom. You can always see the sun glittering above you, even if it takes several minutes for you to surface.

There’s a rustling in the grass, and I turn. A pika stumbles through the blades. He is half rabbit, half mouse, a sprig of fireweed clenched between his teeth. He blinks, maybe surprised to see someone this far out of Ulan.

“I didn’t mean to disturb you,” I say, and his nose twitches, the fireweed sticking up at an angle as he tries to stuff another piece into his greedy mouth.

I smooth my red dress beneath me as I sit down, the pika scurrying off with his prize. I dangle my legs over the edge of the cliff, tapping my heels against the smooth dirt that crumbles down the side of the continent. The sun shines brightly above, the cool morning air gusting around me. I don’t fear falling. The world below looks unreal and distant, like it’s only been painted on. Falling is something I can’t even imagine.

How many monsters run freely down there now? Thousands? Millions? Sometimes you can see something soaring below the clouds, larger than a bird but too far to distinguish its shape. From here the forests of earth below look quiet, fake and imagined. The shadow of our continent blots out the sunlight for what must be miles across the infested landscape. When Ashra lifted into the sky, it left behind a dark and jagged chasm in the earth the annals call the shadowlands. None of us know much about it, of course, whether it’s completely in darkness or what might lurk in those caverns and crevices. From here I can only see the edge of the darkness.

“Kali!” A voice shouts, and it startles me. I lurch forward, digging the palms of my hands into the grass as my heart catches in my throat. My shoe falls from my foot as I tense, and it tumbles toward the suddenly real forest miles below as I gasp in the cool air, gripping the blades of grass with shaking fingers. Slowly, carefully, I slide back from the edge, pulling my legs underneath me. The slipper looks like the back of a sunbird now, small and crimson as it dives toward the mystery below. I stare at my bare foot. What am I going to tell my father?

“Kali!” the voice calls again. I take another breath and stand, walking back toward the outcrop. The pika is nowhere to be seen, and the blades of grass tickle against my sole.

I see her right away, her hands cupped around her mouth as she leans over the base of the rock bridge up to my realm of one. “Elisha!” I shout down. “You nearly sent me tumbling over the edge!”

“You’re being dramatic,” she says. Her black curly hair is pulled back with a looping purple ribbon, her cream tunic fluttering over her olive slacks. “You do realize the ceremony starts in half an hour, right?”

I sigh, looking down at my bare foot.

“So?” she says, resting her hands on the front of her legs. “Let’s go!”

“One minute,” I say, and I turn around to the burst of wildflowers for one last moment before I start down the steep outcrop. The jagged edges of rock slice against the sole of my foot as I climb, the dust gathering on the front of my dress.

“What happened to your shoe?” she asks.

“I lost it when you yelled at me,” I say to the rock surface. You’d think Elisha would worry about distracting me on this narrow rock bridge, but she knows I’ve climbed it a hundred times. She thinks I’m as invincible as I do.

“So you’re going to do the ceremony in one shoe?” She giggles. “I’m sure the Elders won’t notice.”

“If they do, you’re the one who’ll be in trouble.”

“Sure,” she says, rolling her eyes. We both know I’m the one who gets in trouble, even when it’s her fault.

My feet finally touch the long grasses at the bottom of the outcrop, and I push myself upright.

“Ashes, your dress,” she says, and then her hands are all over my robe, trying to wipe off the dusty grains of rock embedded in the fabric.

I laugh. “They do look like ashes. Maybe I’ll get bonus points for authenticity.”

Elisha rolls her eyes. “Let’s hope you rise anew when Aban kills you.”

“Blasphemy,” I tease in Aban’s deep voice, and we both snicker as the wind gusts at our clothes and hair.

Then the bell tolls in Ulan, and the smirks drop from our faces.

“Come on,” Elisha says, grabbing my hand. We run toward the village and the citadel, standing proudly in the distance, its tower made entirely of blue crystal.

Elisha is the only one who knows the real me. We’ve been friends since I wandered into Ulan when I was three and deathly bored. Her family lives in the village, and I visit often. The population is smaller now after the Rending, so hierarchy doesn’t mean as much as it did in ancient times. But my father is still heralded as the Monarch, and he insists on some amount of pomp and display. He says it settles people to know someone’s in charge. They feel at ease knowing there’s someone noble and dignified watching over them, whose life is dedicated to serving them and their best interests. So I carry on all removed and dignified in front of the villagers, and it’s only Elisha who sees me for who I really am—another girl, like her, who wants to pull funny faces and drop buckets of water on the Elders and climb the outcrops of Ashra. A girl who wants to squelch handfuls of sand at the bottom of Lake Agur and come up just as her lungs are bursting. Someone who’s free, who flies through the wind like a sunbird or a butterfly. Someone like Elisha.

But that isn’t who I get to be. I’m Princess Kallima, daughter of the Monarch, heiress of the Red Plume and all of Ashra. The Eternal Flame of Hope for what’s left of mankind.

I’m the wick and the wax, my father always tells me. I must burn for others, even if it means I will burn and crumble for those whose path I light. “We cannot return to those dark days,” he says, and I know he’s right, but it doesn’t mean I always like it.

The dusty sand of the roadway feels hard and cool against my bare sole as we run toward the citadel. A hum grows louder in the distance, the vibration echoing through me as we hurry. It seems too far away as I gasp more air into my lungs.

A dark shadow casts over us, an oval of darkness on the ground that moves faster than we can keep up with. I glance around the blue sky and see it, the wooden belly of the airship as it creaks and hums its way past us. The gears on the sides spin and the plum-colored balloon wobbles back and forth in what little breeze there is, but it’s the humming engine that keeps it moving through the air toward the landing pitch.