По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

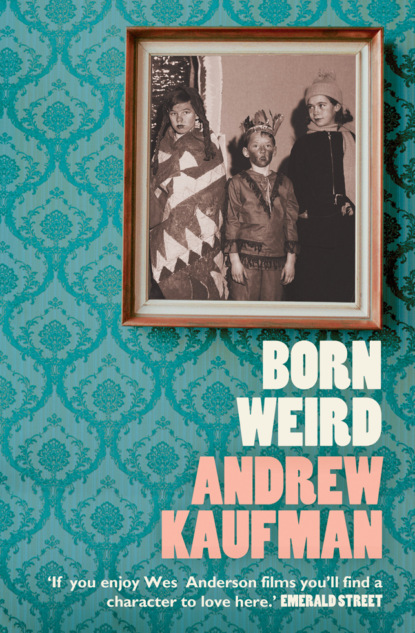

Born Weird

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

In the morning Angie woke up with stiff legs and a sore back. She took tiny steps into the kitchen, where Lucy had already made breakfast.

“Do you drink coffee yet?” Lucy asked. Angie shook her head no. Lucy poured her a glass of orange juice. The hardboiled eggs were perfectly timed. The toast was golden. Their taxi arrived at 8:55. Lucy’s suitcase was already at the door and Angie rushed to collect her things. Checking the lock three times, Lucy then carried both of their bags to the sidewalk. Here they stood for several moments as Angie inspected the cab.

In 1963 Angie’s grandfather Samuel D. Weird founded the Grace Taxi Service. He named the enterprise after his mother. When Besnard took over the business, in 1982, it had grown into the second largest fleet in the city of Toronto.

Over time Besnard developed many theories about taxis. For one, he believed that you should make a wish while hailing a cab. If the first taxi that passed by stopped and picked you up, your wish would come true. He also felt that every taxi ride was metaphorical—that it could be interpreted, like tea leaves or the lines in your palm. But his most firmly held theory was that your choice of taxi was a reflection of how you saw yourself. Of all his theories, this was the one that had been most firmly passed on to his children.

“No visible dents or scratches,” Angie said. She circled the cab slowly.

“You still do this?”

“I would have liked a newer model,” Angie said as she came back around to the back passenger door.

“Not in this town.”

“Really?”

“ ‘Fraid so.”

“Okay, let’s take it,” Angie said. She slid into the back seat. “To the airport,” she told the driver.

“But first,” Lucy said as she got into the back seat and closed the door, “the Golden Sunsets Retirement Community, 170 Lipton Street.”

“I didn’t think you meant right away,” Angie said.

“Well, when did you think I meant?”

“I don’t know. Soonish? You know. In the near future.”

Lucy rolled her eyes. Six minutes later the cab stopped in front of 170 Lipton Street. The exterior of the Golden Sunsets Retirement Community was concrete and depressing. It was worse inside. Decades of wheelchairs had worn twin tracks into the thin grey carpet. The grandfather clock in the lobby leaned to the left. It smelled like medicine and the walls were painted a yellow that was much too optimistic.

“Is this really the best we can afford?” Angie asked.

“This is more than we can afford.”

They walked down the corridor. Angie tried not to look into the rooms. She failed. Some of the residents met her eyes. Others just stared through her. But most disturbing to Angie were their haircuts—zigzag patterns and asymmetrical bobs and parts that started just above the ear. Every single resident there sported a hairdo that looked suspiciously like Lucy’s.

“What’s with the hair?” Angie asked.

“You’ll see,” Lucy said, and she pressed the down button. The elevator arrived and they stepped inside. Neither spoke. When the doors opened for B2, Lucy pointed to a handwritten cardboard sign masking-taped directly across the hall. The sign read:

IT’S ABOUT TIME HAIR CUTTING SALOON

Angie stepped out of the elevator. The doors began to close. “I’d go with you but I’ve just had mine done,” Lucy said.

“This is for real?” Angie asked her.

“Don’t worry,” Lucy said. She held out her hand. The doors jumped back open. “She won’t even recognize you.”

Lucy removed her hand. The elevator closed. Angie took three steps forwards. She stood in front of the door that the sign was taped to. The handle was long and metal. Angie held it for several seconds. Then she pushed it down and went inside.

The room was obviously a disused janitor’s closet. It was small and lit by a single floor lamp. A shelf made of two-by-fours and plywood covered the back wall. There was a sink in the corner. Several mops hung to the right of it. Across from the sink was a wooden kitchen chair on which her mother slept.

Angie watched her sleep. She counted to sixty in her head. She gave the door a good shove, and Nicola woke up.

“Can I help you?”

“It’s me. Angie,” she said. She watched Nicola carefully. For a fraction of a second Angie was sure that her mother recognized her. But the look quickly disappeared and, once again, Angie couldn’t be sure if she’d caught her or imagined something that wasn’t there.

“You’re here for a haircut?”

“It’s me. Your fourth born. Angie.”

“You’re in luck. Mr. Weston cancelled.”

“I’m about to have a baby …”

“I guess I should say he was cancelled.”

“Really? Nothing?”

“God rest his soul,” Nicola said. She picked up the chair, turned it around and set it backwards in front of the sink. She patted it and Angie sat down. Her mother tied a peach-coloured beach towel around her neck. She touched Angie’s forehead, gently encouraging her to tilt back her head. Nicola washed Angie’s hair. The water was warm. The shampoo smelled like goat’s milk soap, which made Angie remember bathtubs full of siblings in their house on Palmerston Boulevard. She drifted off to sleep. She woke up with wet hair.

“You must be tired.”

“I didn’t feel that tired.”

“Something about this room just makes people wanna sleep,” Nicola said. She pulled a white towel from the far wall, revealing a mirror. “Nothing worse than staring at yourself all day,” she said.

Angie stood and Nicola moved the chair in front of the mirror. Angie sat down. She looked at her mother’s reflection. Nicola gathered Angie’s wet hair and let it fall over her shoulders.

“What were you thinking?”

“A trim?”

“I think it needs more than that.”

“No. Oh no. You know? Just a trim.”

“Why don’t you let me try something?”

“A trim is all I need. Really.”

Nicola nodded in agreement. She reached for her scissors, took a five-inch length of her daughter’s hair between her fingers and with a firm unhesitating motion, cut. A length of black hair dropped to the floor. Angie stared at it. A second clump, even longer, fell beside it. In the mirror she saw a third length between the jaws of her mother’s scissors and as they started to close, Angie shut her eyes.

“How far along are you?”

“Hmmm?”