По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

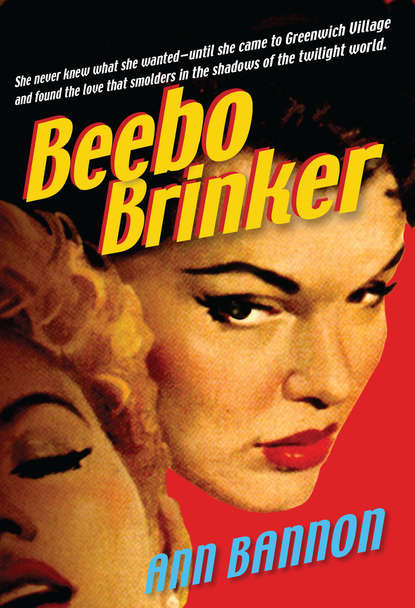

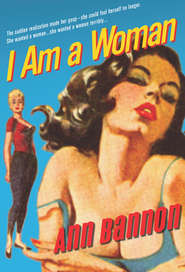

Beebo Brinker

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He took out an ornate bottle, broke the seal and pulled the cork, and got down a liqueur glass. When he up-ended the bottle, a rich green liquid came out, moving at about the speed of cod-liver oil and looking like some dollar-an-ounce shampoo for Park Avenue lovelies. The pungent fumes of peppermint penetrated every crack in the wall.

“What is it?” Beebo said, intimidated by the looks of it.

“Peppermint schnapps,” Jack said. “God. It’s even worse than I thought. Want to chicken out?”

“I grew up in a town full of German farmers,” she said. “I should take to schnapps like a kid to candy.”

Jack handed over the glass. “Okay, it’s your stomach. Just don’t get tanked on the stuff.”

“I just want a taste. You make me feel babyish about the milk.”

He picked up his beer and the schnapps bottle, and she followed him into the living room. “You can drink all the milk you want, honey,” he said, settling into a leather arm chair, “before the sun goes over the yardarm. After that, we switch to spirits.”

He turned on a phonograph nearby and turned the sound low. Beebo sat down a few feet from him on the floor, pulling her skirt primly over her knees. She seemed awkward in it, like a girl reared in jeans or jodhpurs. Jack studied her while she took a sip of the schnapps, and returned her smile when she looked up at him. “Good,” she said. “Like the sundaes we used to get after the Saturday afternoon movie.”

She was a strangely winning girl. Despite her size, her pink cheeks and firm-muscled limbs, she seemed to need caring for. At one moment she seemed wise and sad beyond her years, like a girl who has been forced to grow up in a hothouse hurry. At the next, she was a picture of rural naïveté that moved Jack; made him like her and want to help her.

She wore a sporty jacket, the kind with a gold thread emblem on the breast pocket; a man’s white shirt, open at the throat, tie-less and gray with travel dust; a straight tan cotton skirt that hugged her small hips; white socks and tennis shoes. Her short hair had been combed without the manufactured curls and varnished waves that marked so many teenagers. It was neat, but the natural curl was slowly fighting free of the imposed order.

Her eyes were an off-blue, and that was where the sadness showed. They darted around the room, moving constantly, searching the shadows, trying to assure her, visually at least, that there was nothing to fear.

“What are you doing here in New York, Beebo?” Jack asked her.

She looked into her glass and emptied it before she answered him. “Looking for a job,” she said. “Me and everybody else, I guess.”

“What kind of job?”

“I don’t know,” she said softly. “Could I have a little more of that stuff?” He handed the bottle down to her. “It’s not half as bad as it looks.”

“Did you have a job back home?” he asked.

“No. I—I just finished high school.”

“In the middle of May?” His brow puckered. “When I was in school they used to keep us there till June, at least.”

“Well, I—you see—it’s farm country,” she stammered. “They let kids out early for spring planting.”

“Jesus, honey, they gave that up in the last century.”

“Not the little towns,” she said, suddenly on guard.

Jack looked at his shoes, unwilling to distress her. “Your dad’s a farmer, then?” he said.

“No, a vet.” She was proud of it. “An animal doctor.”

“Oh. What was he planting in the middle of May—chickens?”

Beebo clamped her jaws together. He could see the muscles knot under her skin. “If they let the farmer’s kids out early, they have to let the vet’s kids out, too,” she said, trying to be calm. “Everyone at the same time.”

“Okay, don’t get mad,” he said and offered her a cigarette. She took it after a pause that verged on a sulk, but insisted on lighting it for herself. It evidently bothered her to let him perform the small masculine courtesies for her, as if they were an encroachment on her independence.

“So what did they teach you in high school? Typing? Shorthand?” Jack said. “What can you do?”

Beebo blew smoke through her nose and finally gave him a woeful smile. “I can castrate a hog,” she said. “I can deliver a calf. I can jump a horse and I can run like hell.” She made a small sardonic laugh deep in her throat. “God knows they need me in New York City.”

Jack patted her shoulder. “You’ll go straight to the top, honey,” he said. “But not here. Out west somewhere.”

“It has to be here, even if I have to dig ditches,” she said, and the wry amusement had left her. “I’m not going home.”

“Where’s home?”

“Wisconsin. A little farming town west of Milwaukee. Juniper Hill.”

“Lots of cheese, beer, and German burghers?” he said.

“Lots of mean-minded puritans,” she said bitterly. “Lots of hard hearts and empty heads. For me … lots of heartache and not much more.”

“Why?” he said gently.

She looked away, pouring some more schnapps for herself. Jack was glad she had a small glass.

“Why did you ditch Juniper Hill, Beebo?” he persisted.

“I—just got into some trouble and ran away. Old story.”

“And your parents disowned you?”

“No. I only have my father—my mother died years ago. My father wanted me to stay. But I’d had it.”

Jack saw her chin tremble and he got up and brought her a box of tissues. “Hell, I’m sorry,” he said. “I’m too nosy. I thought it might help to talk it out a little.”

“It might,” she conceded, “but not now.” She sat rigidly, trying to check her emotion. Jack admired her dignity. After a moment she added, “My father—is a damn good man. He loves me and he tries to understand me. He’s the only one who does.”

“You mean the only one in Juniper Hill,” Jack said. “I’m doing my damnedest to understand you too, Beebo.”

She relented a little from her stiff reserve and said, “I don’t know why you should, but—thanks.”

“There must be other people in your life who tried to help, honey,” he said. “Friends, sisters, brothers—”

“One brother,” she said acidly. “Everything I ever did was inside-out, ass-backwards, and dead wrong as far as Jim was concerned. I humiliated him and he hated me for it. Oh, I was no dreamboat. I know that. I deserved a wallop now and then. But not when I was down.”

“That’s the way things go between brothers and sisters,” Jack said. “They’re supposed to fight.”

“You don’t understand the reason.”

“Explain it to me, then.” Jack saw the tremor in her hand when she ditched her cigarette. He let her finish another glassful of schnapps, hoping it might relax her. Then he said, “Tell me the real reason why you left Juniper Hill.”

She answered at last in a dull voice, as if it didn’t matter any more who knew the truth. “I was kicked out of school.”