По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

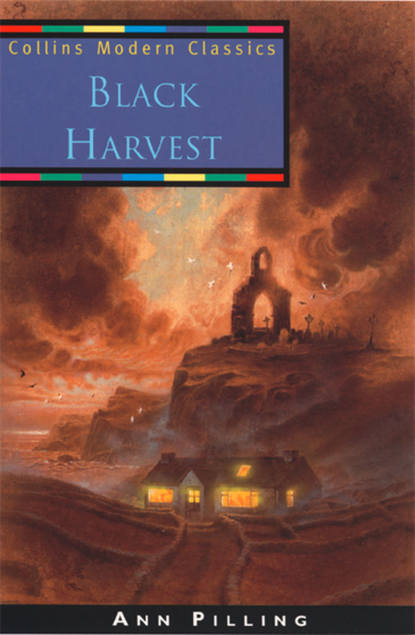

Black Harvest

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

She shouted in her sleep and woke up suddenly. She was out of bed and standing by the open window breathing in great lungfuls of air. It was getting light. The small green field was misty, the air fresh and cool. The countryside and sea were very peaceful in the early dawn.

In the quietness she heard a light click on and then the baby started crying. She had been yelling on and off all night. Prill went down the hall to the kitchen and found Colin there, talking to his mother. He wore nothing except his blue pyjama trousers and his face looked hot. Mum had just stuck a thermometer into his mouth. She looked relieved to see Prill.

“Oh, hello, love. So you couldn’t sleep either. Now we’re all awake, except Oliver. I’ll have to get a doctor to look at Alison. She’s only had about two hours’ sleep all night. Just look at her.”

She looked. The baby wasn’t pink, like Colin, she was turkey red and her whole body was tense. Prill picked her up and tried to slip a finger into the tiny hand; she loved it when the little fingers curled tightly round her own. But Alison wouldn’t respond. Both her hands were clenched up into hard little knots, and she was wailing.

“Has she been eating?”

“Yes. That’s what I don’t understand. It’s not as if she’s hungry. How can she be?”

“Perhaps she’s got what I’ve got,” Colin mumbled, removing the thermometer and reading it. “I feel most odd. Oh, that’s funny. My temperature’s not up, Mum.”

The electric kettle clicked off. “Let’s have some tea,” Mrs Blakeman said wearily. “When in doubt have a cup of tea.” She was trying to sound cheerful but Prill wasn’t fooled, she looked so tired and strained, not a bit like her usual self. She didn’t panic easily. “Do you drink Oliver would like some?”

“Oh, he’s still dead to the world,” Colin said. “I should think he’s the only one who’s had a good night’s sleep, lucky devil!”

Prill took the milk jug out of the fridge. The smell made her wrinkle her nose up. “Ugh! We can’t use this, Mum. It’s off.”

“It can’t be. The O’Malley boy brought it straight up from their dairy. It was chilled. Anyway, I used it at supper, Oliver had some Ovaltine.”

“Well, it’s off now.”

Colin took the large brown jug and sniffed, then he carried it to the sink and looked more closely under the electric strip light. The contents of the jug had solidified completely, they were now greyish, and a fine hair was forming on the thick, wrinkled skin.

He upturned the jug into the sink and a slimy gel plopped out on to the stainless steel. There was a sharp, bitter smell.

“It must be the fridge,” Mum said, more concerned about the whimpering baby. “Perhaps there’s a lemon. We could have that with our tea.”

“The fridge light’s on,” Colin said numbly. “And the motor’s going, listen. It’s working all right.” In the quietness they could hear the motor humming gently.

“This fridge is brand new,” Prill pointed out. “Look, they’ve not even taken the label off it.”

Colin carefully washed the stinking mess down the sink. Prill came up and looked over his shoulder. “I wish Dad was here,” he muttered, out of the side of his mouth so Mrs Blakeman couldn’t hear him. “I think Alison looks awful.”

Prill was trying to convince herself that the woman outside the window had been a nightmare. She did not succeed, no more than Colin succeeded in persuading himself that he’d imagined that fuzzy growth on his pillow.

“It’s this house,” she whispered back. “I wish we’d never come.”

Chapter Five (#ulink_a823154c-a88f-5026-8cb1-35f82dfa2101)

BUT AS THE earth warmed up and birds started singing, Alison, exhausted by her night’s bawling, fell asleep abruptly in her mother’s arms. Mum crept to the kitchen door and mouthed, “I’m going back to bed for a bit.”

“Good idea. I’m going too,” Prill told Colin. “I feel as if I’ve been awake all night.” She was thinking, Dad’ll be phoning at ten o’clock and I’m going to ask him to come back. I can’t bear it here.

Colin sat in the kitchen for a few minutes, looking out over the sea. He felt quite cold suddenly, but it was going to be another beautiful day. There wasn’t a cloud in sight and the stillness in the air promised another scorcher. He still had hunger pains so he made himself some toast and another mug of lemon tea. Then he found the sleeping bag that Dad had stuffed under the stairs, unrolled it over the damp mattress and fell soundly asleep.

At eight o’clock they were all still sleeping, except Oliver. He got up at seven, dressed stealthily, and crept round the kitchen looking for something to eat. Jessie whined and nosed at his feet. He refilled her bowl with fresh water, holding it at arm’s length in case she bit him. He was frightened of dogs. Then he went outside, selected a spade, and started to dig his hole. His uncle David had told Colin on the phone that he was allowed to dig, provided he left the earth in a tidy pile.

The other two didn’t get up again till half past ten and by then Colin was ravenous. He sat at the kitchen table eating cornflakes, toast, eggs and bacon. All the windows were wide open. They could hear Oliver scraping away at his hole and talking to Kevin O’Malley who’d walked down with the milk. Mixed with the smell of fields was the tang of the sea.

“There’s not much wrong with you,” Prill said. “I don’t know how you can eat all that.”

“I was hungry,” Colin said simply. “It woke me up in the night.”

“Was that all that woke you?”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, you were in the kitchen at five o’clock.”

“So were you.”

They stared at each other, Prill with a look that said, “You first”. Colin pressed his lips together. Prill was nervous sometimes. When they were little he used to get into awful rows for jumping out at her and making spooky noises. She still slept with the landing light on.

“What was the matter?” she asked him.

He hesitated.

“Come on, Colin!” her voice was strained, almost angry. It wasn’t like Prill. He was supposed to be the moody one.

“Well, it sounds so stupid… It was weird. I woke up because I was too hot, and my bed felt terribly damp, and… there was a kind of, well, mould all over it.”

“Mould?”

“Yes, honestly, and it smelt peculiar too, horribly musty.”

She stood up. “Show it to me.”

“It’s no good, Prill, not now. Sit down, will you? I can’t. It wasn’t there when I woke up just now. Everything had, well, you know, gone back to normal. The sheets are a bit dirty, that’s all. I was probably dreaming.”

She was silent. A wave of fear rose inside her then ebbed away, leaving her numb and cold. “That makes it worse,” she said.

“What do you mean?”

“The fact that it’s all so…ordinary this morning. It’s like that smell on the beach. It was there. But you just said I must have imagined it.”

“You didn’t imagine it. I could smell it too, last night. I was nearly sick.” He paused. “What woke you up, the same thing?”

“No… no. It was Alison, yelling her head off. Then, when I did get to sleep, I had a kind of nightmare. It was about Donal Morrissey but he’d, sort of, turned into a woman. She looked more like a skeleton. Ugh, it was horrible.”

She wouldn’t say any more. Shaking her head violently, as if this would shatter the picture in her mind of the woman crawling over the field, she went to the wall-phone and started dialling.

“What are you doing?”

“Phoning Dad.”

“Why?”