По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

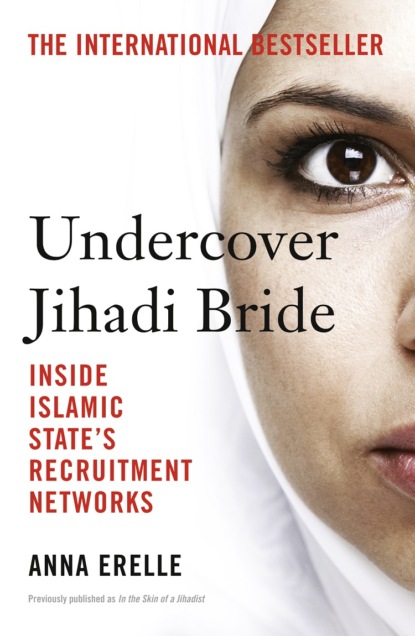

Undercover Jihadi Bride: Inside Islamic State’s Recruitment Networks

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Capitalism, my dear, is a blight on the world. While you’re busy eating Snickers bars, watching MTV, buying Booba or Wu-Tang Clan albums, and window-shopping at Foot Locker, dozens of our people are dying every day so that we Muslims can live in our own state. While we’re out risking our lives, you’re spending your days doing meaningless activities. Being religious means imposing your values. I’m worried about you, Mélodie, because I sense that you have a good soul, and if you continue to live among kafirs, you’ll burn in hell. Capitalism is exploitation of man by man, do you know what I mean?”

Now he was referencing Marx. Did he really grasp the German philosopher’s doctrine and his concept of class struggle? Or was he simply repeating something he’d heard from someone else? I thought of Guitone, the Islamic State’s “publicist,” who dressed head to toe in Lacoste. Mélodie was stunned by the fate Bilel described for “kafirs.” Her life in the West offered no hope, but was it really so bleak, compared to what Syrians endured? Bilel sought to infuse her faith with fear. He succeeded in sowing doubt in her mind and making her feel extremely guilty.

Abu Bilel was diabolical. I examined his profile picture. He was rather good-looking. The stunning grammatical errors barely distracted from the force of his conviction. What had drawn him to radicalism? What had made him so blindly committed—and therefore particularly dangerous? Some parents of jihadists compare the indoctrination of their children to methods used by cults. There was something of that here. Bilel acted as a kind of guru, who presented war as a divine mission. Mélodie was to accomplish her mission for the sake of a prophecy she didn’t understand. I lit another cigarette.

“Are you saying that if I don’t go to al-Sham, I’ll be a bad Muslim, and I’ll never know heaven?”

“Exactly . . . but you still have time. I’ll help you. I’ll be your protector. Can I ask you a question?”

Another smiley face; it had been a while. Mélodie had the choice between Syria and hell. Bilel painted a postcard of Syria that sounded pleasant and not at all hellish.

“I’ve checked out your profile,” he went on, “and I only found one picture. Is it of you?”

Crap! I’d completely forgotten about the picture. I’d created Mélodie’s account six years before, when the wives of extremists could still show their faces. Now the few Islamist radicals who allowed their wives access to social networks made them cover their faces. I hadn’t thought to erase the old profile picture depicting a pretty, fair-haired girl.

“It’s a picture of my older sister,” I improvised. “She hasn’t converted, so she doesn’t cover her face, but I do.”

“You scared me, Masha’Allah! Nobody should be allowed to look at you! A respectable woman only shows herself to her husband. How old are you, Mélodie?”

Until that point, I’d felt like I was conversing with a car salesman; now I had the disturbing sensation of speaking with a pedophile. I wanted to tell him that I was a minor—just to see his reaction. But if I decided to meet him over Skype, that wouldn’t work. I was just over thirty. And even if I looked young for my age, I couldn’t pass for a pubescent teen.

“I’m almost twenty.”

“Can I ask you another question?”

He clearly didn’t care about Mélodie’s age. What if she’d been fifteen? Would he speak to her differently?

It was midnight in Syria, eleven o’clock in France. My pack of Marlboros was empty. I was exhausted, and I sensed his next question would finish me off for the night.

“Do you have a boyfriend?”

Touché. I’d been dreading this moment. Mélodie would have to be succinct. She couldn’t give any details.

“No, I don’t. I don’t feel comfortable talking about this with a man. It’s haram.* My mother will be home from work soon. I have to hide my Koran and go to bed.”

“Soon you won’t have to hide anything, Insha’Allah! I just want to know if I can be your boyfriend?”

“But you don’t know me.”

“So?”

“So what if you’re not attracted to me?”

“You’re sweet. It’s your inner beauty that counts. I have a good feeling about you, and I want to help you lead the life awaiting you here. It breaks my heart to hear that you hide to pray. It’s something I fight for every day here, to make others respect sharia.”

His exploitation of Islam enraged me. Islam, and this is my opinion, is a great religion that encourages its believers to have sympathy for others. I’m agnostic, but I admire this community of people that finds its bearings throughout the world. André Malraux predicted that “the twenty-first century will be religious or will not be at all.” This quote is often taken out of context; Malraux was referring to spirituality and “lofty” feelings. Bilel promoted a doctrine that, among other antiquated practices, forced women to wear full veils and marry at the age of fourteen. Some of these laws are intolerably violent: adulterous women are stoned to death, while men who cheat on their wives are merely fined; thieves pay for their crimes with their hands. ISIS seeks to install sharia law, first in the Middle East, then throughout the world.

When it came to sharia, Bilel was professorial: Mélodie was not to show an inch of her body, not even her hands, to anyone. A veil covering all but the oval of her face was not enough. She needed to wear a burqa and an additional veil over it. His pronouncements grated on me.

“My mother raised my sister and me by herself,” I began, trying to calm things down. “She works two part-time jobs to make sure we have everything we need. I converted in secret. She isn’t preventing me from practicing my religion.”

“I’m sure your mother is a good person; she’s just lost her way. I hope she’ll soon return to the right path—the one and only—Allah’s path.”

I was dumbstruck by his rigid thinking, bad faith, and blind judgments. Still, his arguments were relatively coherent, if ideologically impoverished. Bilel met Mélodie’s questions with the most basic doublespeak: all the answers could be found in Islam—the medieval version of Islam promoted by ISIS. This conversation had gone on too long, and it was time to put an end to it. Mélodie reminded Bilel that she had to go to bed. He gave in and wished her sweet dreams, then added, “Before you go to sleep, answer me something: can I be your boyfriend?”

I logged off Facebook.

We’d exchanged one hundred twenty messages in the space of two hours. I carefully reread them all. Late in the night, I called Milan.

Monday (#ua7c63389-a74d-5013-b97f-7f9a8c0f4eb4)

I woke up early, which is unusual for me. I rushed to the magazine where I often do freelance work, eager to discuss my weekend with one of the editors in chief. He also tracked the growth of Islamist extremist groups on the Net. Twenty-four hours earlier, I’d forwarded him the video of Bilel showing off the contents of his car. He was stunned by how easily contact had been established. He agreed that this was a unique opportunity. Information obtained in this investigation could provide a singular perspective on digital jihadism. However, he reminded me that pursuing this could be dangerous. Urging caution, he also assigned me a photographer, André, one of my best friends and also a freelancer. We’d worked together for years, and we made a good team. I would agree to Bilel’s request to meet over Skype, and André would take pictures. After me, André would be the second witness to Bilel and Mélodie’s relationship.

It suddenly struck me as strange to be playing one of two protagonists in a fabricated story, with both of us dealing in half-truths. I had never done something like this before, and it was troubling. So far, Bilel had been an evil genie I could consult whenever the need arose. Now I found myself implicated in the story. I would have to satisfy his need for domination, but for the time being, I was preoccupied with a single, urgent detail: how to become Mélodie. I needed to look ten years younger, find a veil, and somehow slip into the skin of a very young woman. Another editor, a former reporter who would also be supervising my investigation, lent me a hijab* and a black dress—a kind of djellaba. Bilel wouldn’t speak with Mélodie if she didn’t hide the majority of her body. He was thirty-eight, and his attitude toward women was not the same as that of a young, newly recruited jihadist.

I was glad to wear the veil. The idea of a terrorist becoming familiar with my face didn’t thrill me, especially not when the man in question could return to France, his home country, at any moment.

André arrived at my apartment that night around six o’clock. It was one hour later in Syria. That gave us about sixty minutes to prepare before Bilel “got home from fighting” and contacted Mélodie. We looked for the best angle from which to take pictures of the computer screen and keep me as indistinct as possible. We had strict orders to prioritize André’s and my safety above all else. While André made adjustments in the living room, I pulled on Mélodie’s somber clothing over my jeans and sweater. The floor-length black djellaba featured a small satin knot at the waist and was surprisingly fitted. I took a picture with my phone of the long train covering my Converse sneakers. I really looked like I was twenty years old. When I returned to the living room, André burst out laughing. “It’s supposed to cover more of your forehead,” he said, mocking me as he snapped a picture. He helped me readjust the hijab, which should cover every strand of hair and only show the oval of the face. I’ve worn burqas before, while working on other stories. I’ve never found them suffocating, as some women describe. People tend to regard you as oppressed when you wear a burqa, but the piece of clothing itself has never bothered me. The hijab, however, was a new experience. It reminded me of the horrible hoodlike knitted caps my parents forced on me as a child. It made my skin itch as it had when I was five years old, and my face looked like a puckered fish. André’s hysterical laughter didn’t help things.

I removed my rings, assuming Bilel wouldn’t appreciate such frivolousness. Besides, if I wanted to become Mélodie, I had to remove all distinctive signs of myself. She wouldn’t wear flashy rings. I also covered the small tattoo on my wrist with foundation. I had meant to buy nail polish remover to erase the bright red from my fingernails. I’d forgotten. Oh well. If Bilel said anything, I’d make up some excuse.

The hour was approaching. Perceiving my feelings of impatience, excitement, doubt, and fear, André tried to calm my nerves by talking about something else. To be clear, I wasn’t afraid of the terrorist I was about to meet; I’d Skyped with others like him before. Rather, I sensed I was about to learn a lot, and I was afraid Mélodie wouldn’t be able to handle it. As soon as I turned on my computer, I saw that Abu Bilel was already logged on to Facebook and waiting for Mélodie.

“Are you there?” he asked impatiently.

“Are we meeting on Skype?”

“Mélodie?”

“Hello? LOL.”

“Mélodie???” . . . “Sorry: salaam alaikum . . .

You there???”

Monday, 8 p.m. (#ua7c63389-a74d-5013-b97f-7f9a8c0f4eb4)

Okay. It was time. I sat cross-legged on my sofa. It had a high back, which hid most of my apartment—and any distinctive features—from the camera. André had also removed from the wall a famous photograph taken in Libya three years earlier. He positioned himself in a blind spot behind the sofa. Mélodie bought some time by typing a reply to Bilel. My smartphone was already recording. I was also equipped with another, prepaid phone I’d bought a few hours earlier. The Islamic State is brimming with counterespionage experts and hackers. It was safer if Bilel didn’t know my phone number, so Mélodie had her own. I’d also created a new Skype account in her name. I’d found a video on YouTube explaining how to scramble an IP address. If things started to go wrong, Bilel wouldn’t know where to find me.

The Skype ringtone sounded like a church bell tolling in a dreary village. If I pressed the green icon, I would become Mélodie. I took a moment to breathe. Then I clicked the button, and there he was. He saw me, too. For a split second, we didn’t speak. Bilel stared at Mélodie. His eyes were still accentuated with dark liner. They smoldered as he gazed at the young Mélodie, as if trying to cast a spell. I don’t know if it was because I was nervous about meeting this man face-to-face, but in any case what captured my attention most was his location. Bilel was Skyping Mélodie from his car, using a state-of-the-art smartphone. He lived in a country often deprived of water and electricity, yet he had access to the latest technological devices. The connection was good, which was not always the case in such circumstances. Bilel made ISIS sound more like a nongovernmental organization than a terrorist group, but one would never confuse him with a humanitarian aid worker. He looked clean and even well-groomed after his day on the front. He was a proud man, his shoulders pulled back and his chin thrust forward, but I sensed he was nervous meeting Mélodie. After what felt like an eternity, he finally broke the silence:

“Salaam alaikum, my sister.”

I made my voice as tiny, and as sweet and bright, as I could, considering I’d smoked like a chimney for the past fifteen years. And I smiled. My smile instantly became my best defense mechanism, and it remained so throughout my investigation. I would use it whenever I didn’t know how to react. I believed I could become another woman by playing the understanding friend. But I couldn’t bear the thought of watching the videos André was going to film of these virtual discussions. Today, when I watch them, I don’t see the pure and naïve Mélodie; for me, she isn’t the person I see smiling and impressed as she converses with Bilel. I see myself, Anna, dressed in black, sitting on my familiar couch, which I have come to hate. I’m the girl smiling. It isn’t Mélodie; she doesn’t exist. Should I feel ashamed for having taken part in this exercise? I’m a private person, and when I see these images of myself—playing a part, but it’s still me—I feel sick.

Mélodie replied using the same polite expression, but she didn’t finish her phrase. André distracted me by jumping around the sofa and waving his arms, careful not to enter the camera’s field of vision. In the heat of the action, I hadn’t replied correctly to Bilel’s question. The proper response to “salaam alaikum” is “walaikum salaam.” It was a beginner’s mistake, and I knew better. I wanted to laugh, and at the same time, I would’ve liked to see André in my shoes! But I couldn’t do anything; Bilel was hanging on Mélodie’s every word. He may have been in Syria, and I in France, but our faces were separated by mere millimeters. I had to be careful not to let my eyes wander from the screen. I was flooded with random thoughts. Ignoring André, who was still jumping around like a kangaroo, I choked when I heard Bilel’s first question.

“What’s new?”