По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

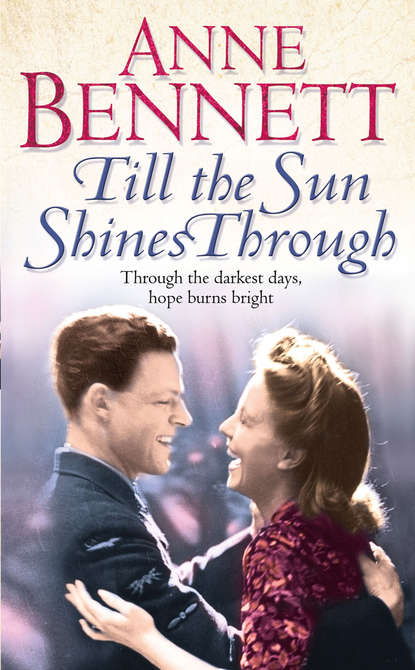

Till the Sun Shines Through

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

There were four hard-boiled eggs, slices of ham and others of cheese, and slices of thickly buttered soda bread, large pieces of barn brack and half a dozen scones. ‘I have milk too,’ Tom said, producing the bottle. ‘My mother insisted on lacing it with whisky “to keep the cold from my bones” she said.’

Bridie had never drunk laced milk before; she’d never tasted whisky at all. But she found it was very pleasant indeed and considered Tom’s mother a wise woman for thinking of it for it certainly warmed her up. The food also put new heart into her and made her more hopeful about the future, whatever it held.

When this was all over, she thought, maybe she could make it up to her mother and father for running away and certainly beg their forgiveness. Surely to God they wouldn’t hate her for ever?

‘I’m glad you have someone to lodge with,’ Tom said suddenly, breaking in on her thoughts. ‘Birmingham, like most cities, is a depressed place. The people back home seem to think you can peel the gold from the city’s streets.’

‘But how would they know how it is?’ Bridie said. ‘Many of our neighbours have travelled nowhere all the days of their life except into town on a Fair Day.’

‘Yes, you’re right,’ Tom agreed. ‘Still you have someone anyway. Where’s your sister meeting you?’

‘At New Street Station,’ Bridie said. ‘At least … I must send her a telegram to tell her the times of the trains.’

‘There’ll be plenty of time when we get to Liverpool for that, I should think,’ Tom said. ‘I lived there for some time, so I know my way about.’

‘Did you? Why did you leave?’

‘Oh, there were reasons,’ Tom said. That was his cue to tell Bridie all about himself, but he said nothing and instead changed the subject. Though Bridie chatted easily enough, she parried all his questions about her home or family, knowing it would never do for him to guess where she lived and how far she’d come. Instead, she asked Tom questions about himself and was particularly interested in anything he could tell her about Birmingham.

‘But you know it already, surely?’ Tom said. ‘Didn’t you tell me you were over before?’

‘Aye, but I was a child just,’ Bridie said, ‘and my sister was expecting so we didn’t stray far from the house. I went to the cinema a few times, though, to the Broadway near to where they live. That was truly amazing to me, and my cousin Rosalyn was green with envy when I described it. We went to a place called the Bull Ring a time or two as well, though never at night, although Mary said there was great entertainment to be had there on a Saturday. She used to get tired in the evenings, though, and she wasn’t up to long jaunts.’

‘Oh, you missed a treat all right,’ Tom said. ‘The Bull Ring is like a fairyland lit up with gas flares and the place to be on a Saturday evening, if you can shut your eyes to the poverty all around. You must make sure you pay a visit this time and see it for yourself.’

‘I will,’ Bridie promised.

‘There are cinemas too of course,’ Tom said, ‘like the Broadway picture house you mentioned, but I really like the music hall and that’s what I spend my spare money on.’

‘Music hall?’

‘Now there’s a treat if you like,’ Tom said. ‘The city centre is full of theatres and they put on variety shows and some do pantomimes. Have you ever seen a pantomime?’

Bridie shook her head.

‘I didn’t see one myself until I came to live in Birmingham,’ Tom said. ‘But they are very funny, well worth a visit. There was a moment’s pause and then Tom suddenly asked, ‘Do you dance, Bridie?’

‘Dance?’

‘Everywhere you go there are dances being held,’ Tom told her. ‘There are proper places of course, like Tony’s Ballroom and the Locarno, but they’re also held round and about the city centre in church halls and social clubs. There’s often a dance hall above picture houses and even on wooden boards laid across empty swimming baths.’

‘I can’t dance at all,’ Bridie said. ‘Not like that. I know Irish dancing, I mean I can do a jig or reel or hornpipe with the best of them, but I don’t know a thing about other types of dancing.’

‘Well, if you have a mind to learn, there are schools about ready to teach you,’ Tom told her. ‘And sometimes only for coppers.’

‘It sounds such an exciting place to live in, I saw less than half the place last time. I know nothing about these other things,’ Bridie exclaimed.

‘There’s grinding poverty here too,’ Tom reminded her. ‘Sometimes the bravery and stoicism of the average Brummie astounds me. Some families we help are so poor, so downtrodden, and yet they soldier on, their spark of humour still alive. Those lucky enough to be in work fare better, but the hours of work are often long and the jobs are heavy and I can’t blame them for seeking entertainment.’

‘You seem so settled in city life,’ Bridie said. ‘Don’t you miss Ireland?’

‘Not so much now,’ Tom said. ‘I did of course, but I’ve been away from it so long. I miss the peace of it sometimes, the tranquillity that you’d never find in a city, but I feel needed there like I never was on the farm.’

‘So you’d not ever go back to live there?’ Bridie asked.

Tom was a while answering. Eventually he said, ‘Ever is a long time, Bridie. Who knows what the future holds for any of us? But, for the moment at least, my place is there.’

And mine too, Bridie thought, but she didn’t share her thoughts with Tom. She didn’t know what the future held for her either and every time she thought of it, her stomach did a somersault.

Her silence went unnoticed, though, for the train was pulling into Derry and they began to collect their belongings together as they had to change to the normal gauge train for the short journey to Belfast and the ferries for England. Bridie tried to return Tom’s coat, but he refused to have it back and insisted she wrap it around herself, carrying her own sodden one over his arm.

It was on the train that Bridie saw Tom properly for the first time and, now that the light was better, she realised he was a very handsome man. His hair was very dark and a little curly and he had the kindest brown eyes ringed by really long lashes. His nose was slightly long and his mouth wide and turned up and it gave the impression he was constantly amused by something. The whole effect was one of gentleness, kindness, though his chin seemed determined enough.

And then, as if aware of her scrutiny, Tom smiled. It transformed his whole face and Bridie’s heart skipped a beat.

‘I’m glad we’re travelling together, aren’t you?’ Tom said.

Oh yes, Bridie was glad all right, but she thought it best not to say so and instead just smiled. She was not to know how expressive her eyes were, and that Tom was delighted she obviously liked his company, and they chatted together as if they’d known each other years as the train pounded its way towards Belfast.

‘I don’t remember being this sick last time I came,’ Bridie said, wiping her mouth.

‘Aye, but early December is not the ideal time to cross the Irish Sea,’ Tom said, and Bridie looked out at the churning grey water, at the huge rolling breakers crashing against the sides of the side in a froth of white suds.

But, Bridie thought, the extreme sickness might have been due partly to her pregnancy, for she’d been nauseous enough at times without the help of the turbulent sea, but that was a secret she could share with no one and so she kept quiet and tried to control her lurching stomach.

It was too cold and altogether too wet to stay on deck any longer than necessary, but inside the smell was appalling, although the ferry wasn’t so crowded. The place smelt of people and damp clothes and vomit from those who’d not made it outside in time. But prevailing it all was the stink of cigarette smoke that lay like a blue fog in the air and the smell of Guinness.

It gagged in Bridie’s throat as Tom upended his case for her to sit on. ‘Sit there,’ he said. ‘I’ll get you something.’

‘Brandy!’ she said a few moments later. ‘I’ve never tasted brandy.’

Tom sat on his other case beside Bridie and said, ‘Then you’ve not lived. Get it down you. It will settle your stomach.’

‘First laced milk, now brandy,’ Bridie said with a smile. ‘And at this hour of the morning. Dear God, this is terrible.’

‘Aye,’ said Tom, catching her mood. ‘Here’s the two of us turning into lushes. Now drink it down and you’ll feel better.’

‘Oh God!’ Bridie cried with a shiver and a grimace at the first taste of it. ‘It burns. It’s horrible!’

‘Think of it as medicine,’ Tom said, and Bridie held her nose, for even the smell made her feel ill, and swallowed the brandy in one gulp, which left her coughing till her eyes streamed. ‘Maybe the cure is worse than the disease,’ she said eventually, when she had breath to do so.

Tom watched Bridie with a smile on his face, but his thoughts were churning. He’d never much bothered with girls before. In truth, maybe never allowed himself to be attracted to any. He knew all about girls though, hadn’t he got three sisters? But this girl he’d just met was affecting him strangely. It wasn’t her beauty alone, though that was startling enough, especially her enormous brown eyes with just a hint of sadness or worry behind them and her creamy skin. It was much more. She was small and fragile-looking for a start and had such an air of vulnerability.

Tom couldn’t understand how she’d affected him so. Just looking at her, he’d felt a stirring in his loins that was so pleasurable, it was bound to be sinful and his heart thudded against his chest. He wanted to hold her close and protect her against anything that might possibly hurt her or upset her.

Bridie, with no inkling of Tom’s thoughts about her, suddenly yawned in utter weariness. She’d had little sleep except for the bit she’d snatched in Strabane. Her smarting eyes felt very heavy and she closed them for a while to rest them.

But she swayed on the case as sleep almost overcame her and she jerked herself awake again. ‘Are you tired?’ Tom asked, and at Bridie’s brief nod, he went on, ‘Lean against me if you want, I won’t let you fall.’