По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

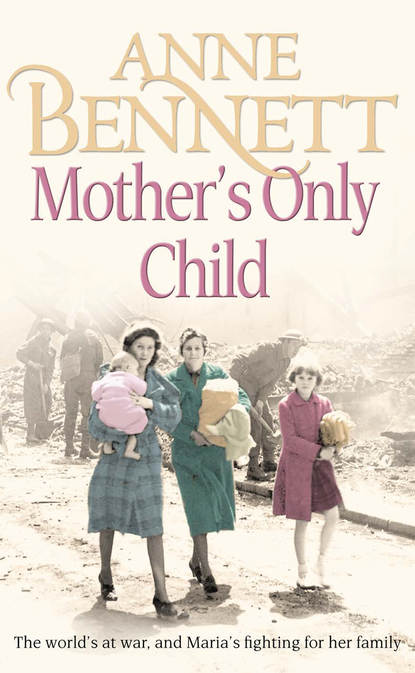

Mother’s Only Child

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Chapter Twenty-six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About The Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Other Books By (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_a70f3d2d-cf66-59e9-bd8a-de4738990c44)

Maria Foley almost ran across The Square that day in late July 1941. The faint summer breeze riffled through her long wavy hair, tied back loosely with a ribbon the same green as her eyes. Bella McFee, catching sight of the girl, stepped out of the post office-cum-grocery shop when she saw the envelope in Maria’s hand.

‘It’s come then?’

‘Aye,’ Maria said. She tried to keep the elation out of her voice. ‘I’ve passed.’

She saw Bella’s lips purse in disapproval and, for a moment, Maria was resentful. She’d worked for Bella in the shop for two years. Couldn’t she just say she was the tiniest bit pleased? Congratulate her even?

Her mother, Sarah, had said the right words—‘Congratulations. You’ve done well’—but in a flat, expressionless and totally insincere tone. However, what Bella did say was, ‘I’m away to see your mother. She’ll likely be feeling low after this. Mammy will mind the shop. And where are you off to in such a tear? You’re not due in till nine.’

‘The boatyard,’ Maria said. ‘I want to see Willie.’

‘Oh, he’d like to know right enough,’ Bella said. ‘But you, Maria, aren’t you the tiniest bit ashamed, wanting to go to some fancy academy in Dublin just now, when you could be a help and support to your mother? Have you no thought for her, and you an only one too?’

Immediately, guilt settled between Maria’s shoulder blades. It isn’t my fault I’m the only one, she wanted to cry. That was the main problem, of course. If her mother had had a houseful of children, she could have taken pride in the fact that her eldest daughter had won a scholarship to the Grafton Academy in Dublin to study Dress and Fabric Design for two years.

But Sarah’s fall down the stairs when Maria had been just eighteen months old had killed the child she was carrying and assured there would be no more either. It had also, so it was said, given her ‘bad nerves’. Maria hadn’t known what ‘bad nerves’ were then, of course, although she knew her father was never willing to upset her mother and strongly discouraged Maria from saying or doing anything that might disturb her at all. She was well aware that the news that morning would have disturbed her greatly, and yet she couldn’t help being pleased and, yes, proud of herself. She knew Willie would congratulate her warmly and, oh God, how she needed someone on her side for once.

‘Mammy should never have let me go in for the exam if she can’t take any joy in the fact that I have passed it,’ Maria said.

‘You don’t understand anything yet, girl,’ Bella said sharply.

Maria flushed at the sharp tone and then tossed her head a little defiantly and said, ‘I have to go, or I’ll be late getting to the shop.’

Before Bella could say another word, Maria gave her a desultory wave and ran over the green to the coastal path, which ran to Greencastle, the next village up Inishowen Peninsular. It was the path her father used to take every day bar Sunday, when he’d owned a boatyard in the small village. Now he worked at the Derry docks, and Willie Brannigan was put in charge of the Greencastle boatyard. He’d known Maria since the day of her birth and she knew he’d wish her well.

She paused on the banks of Lough Foyle, the sun, warm on her back from a cloudless sky, glittering on the water. Well, what could be seen of the water. The lough was so filled with naval craft, she could barely see Milligan’s Point on the further side, the side the British still owned. She couldn’t see the airports at Limavady and Eglinton either, but she knew they were there. It was a fine sight to see the aircraft flying above the flotilla of naval vessels on convoy duty. Her father said they were more effective at sinking German U-boats than the ships. The British-owned six counties had been dragged into the war along with Britain, but the Free State, Maria’s side of the border, had declared itself neutral and Maria knew there were soldiers from the Irish Army stationed at Buncrana, which was the other side of the peninsular, to try to ensure the Germans respected that neutrality

She gave a sigh and made her way to the boatyard. For a moment she wished Greg Hopkins was just a couple of miles away on his father’s farm and she could rush to him with her news, for he was another one who believed she was doing the right thing. He was in the army now and, though she was proud of him, she missed him sorely. Letters couldn’t make up for his absence.

It was strange how she and Greg had always been such friends, because Greg hadn’t been born in Inishowen at all, but in Birmingham, England, where his father came from, though his mother was from Moville.

The whole family had arrived in 1934 when Greg’s mother inherited a farm from an uncle. Maria had only been nine, and Greg thirteen, but she remembered the lost and unhappy boy he was then, who made no effort to make friends. He was like a fish out of water, her mother would say.

‘But, why come here?’ Maria had asked him one day, when he had been there more than a year and was ready to leave school. ‘It seems such an odd thing to do, when you were not born and bred for it.’

Greg had shrugged. ‘Dad hadn’t worked for two years when we came here. He wasn’t the only one, or owt. Many like him were hit by the slump. We were on our beam ends, nearly starving, and when we got the news about the farm out of blue, Dad said it was like a miracle. He’s pulled the farm round and it’s doing all right. At least we all get enough to eat.’

‘Do you like farm work?’

‘I hate it,’ Greg had said fiercely. ‘And I hate this little village—in fact, the whole of Inishowen—and one day I’ll go back to Birmingham. I know I’ll have to wait a while; Phil is only just ten, Billy two years younger still—the girls don’t count—and they wouldn’t be able to be much of a hand to our dad. Anyway, there’s no work for anyone much in Birmingham at the moment, but I don’t intend to stop here all the days of my life.’

But, while Greg had waited, he found Maria to be a fine distraction, especially as she grew and began attending the socials held for the young people at the church. There he danced with her many times, often walked her home and sought her company after Mass.

‘You have an admirer,’ Sarah said. She knew nothing of Greg’s restlessness. All she saw was that Greg was the eldest son and set to inherit the farm, and the family were respectable and God-fearing. If her daughter was to marry Greg Hopkins, Maria would live not far from her parents at all, and that would fulfil Sarah’s dream.

Maria wasn’t ready for any sort of relationship. ‘Don’t be silly, Mammy, he’s just being kind,’ she said. ‘He’s the same with everyone.’

That morning, though, she so wished he was there to tell her news to.

There was another person she wished was still in Moville. Philomena Clarke had been the tutor at the evening classes for dressmaking who had recognised Maria’s quite exceptional talent and knew that she had the chance of winning a scholarship to the Academy. They had gone together to the college in Derry for Maria to take the exam in May, and she had even promised she would travel down to Dublin with her and settle her in.

However, life had a hammer blow waiting to hit Philomena, for the day after the exam she had a telegram from New York from the husband of her twin sister, who had been badly injured in a car accident and was asking for her. Philomena was gone within days and a little after she had left, Maria had a letter from her. Her sister had died, leaving the husband distraught, and she had decided to stay to help him rear his three small children, who were devastated and traumatised by the tragedy.

Maria was touched that even in the middle of that appalling upheaval and upset, while still grieving for her sister, she still had a thought in her head for Maria.

‘Please write and tell me as soon as you get news from the college,’ she had pleaded in her first letter to Maria. ‘I will be on tenterhooks until I hear from you.’

Maria would write to both Greg and Philomena that very night, she decided, and she walked on, composing the letters in her head as she went.

Bella found Sarah in the scullery, washing the breakfast dishes, her red-rimmed eyes betraying the tears she’d shed. Visibly she tried to take a grip on herself when she saw Bella.

‘Shall I make a cup of tea?’ she said. ‘Have you time?’

‘Aye, Mammy’s seeing to the place and Maria will be there at nine.’

‘Maria!’ Sarah said plaintively. ‘What will I do when she leaves, Bella? I’ll be destroyed.’

‘No, you won’t!’ Bella said emphatically. ‘I’ll see you’re not.’

Bella remembered the time Sam Foley had brought his young wife back into the village to live. She’d been only young herself then, and, though married for eight years, she was still childless. Her frustrated maternal instinct was stirred by Sarah, who was only seventeen and looked such a frail and delicate wee thing, with her blonde hair and big blue eyes. The two became good friends.

‘Tom Tall and Butter Ball,’ Bella used to call the two of them, for though Sarah wasn’t that tall, her slenderness made her appear so. Bella was, like her mother, under five foot and ‘as wide and she was high’, she was fond of saying. That wasn’t strictly speaking true, but she was plump and her mother, Dora Carmody, stouter still. Everything about them was round, but their faces were open and friendly and their brown eyes kindly looking. Bella had once had dark blonde hair, but now it was as grey as her mother’s and, like hers, fastened into a bun.

Sam Foley, being the third son, had never thought to inherit the boatyard in Greencastle, nor the family house in nearby Moville. Knowing there would be no opening for him in the family business, his father had apprenticed him to a carpenter friend, who ran his business from a small town called Belleek, in the neighbouring county of Fermanagh, when Sam had been twelve years old.

Sarah Tierney’s family lived not far from the village, on a thriving farm in Derrygonnelly on the banks of the huge Lough Erne, and Sarah often shopped in Belleek with her sisters, Peggy and Mary.

There she met and fell in love with Sam, and he with her. No obstacles were put in the way of her marrying him, for everyone liked the man and knew he was set to inherit the carpentry business, so it was generally thought that Sarah had done well for herself.

Sam’s family had come down for the wedding, and there Sam’s two brothers sought him out and told him they were off to seek their fortune in America as soon as it could be arranged. The boatyard was all his if he wanted it.