По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

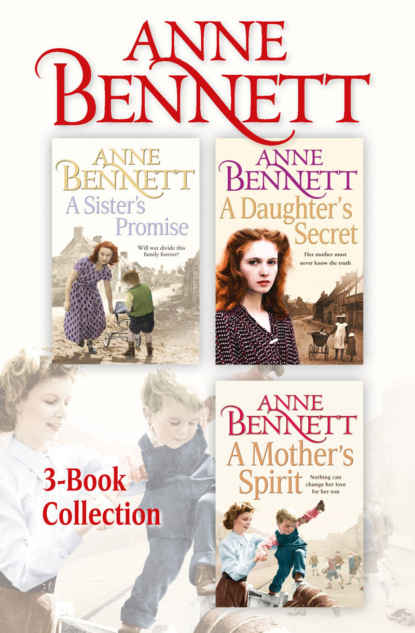

Anne Bennett 3-Book Collection: A Sister’s Promise, A Daughter’s Secret, A Mother’s Spirit

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Molly shook her head. ‘I couldn’t eat another thing. I am almost too full to move already.’

‘I hope you’re not,’ Cathy said. ‘I want to show you the town.’

‘Oh,’ Molly said, ‘I would like that, but shouldn’t we help with washing-up, first?’

‘Not today,’ Nellie said firmly as she began collecting the plates. ‘Maybe when you are a regular visitor here I will let you put your hands in the sink or wield a tea towel, but today make use of the fine evening.’

‘And try and work off that lovely tea.’

‘That as well,’ Nellie said with a smile.

The post office was situated almost at the top of a hill on a wide and straight street with the hills visible in the distance ahead. It was as they walked to the top of it that Molly saw the cinema and she exclaimed in amazement. It was a sizeable cinema too, made of honey-coloured brick with arched doors at the entrance.

‘Why the shock?’ Cathy asked. ‘I’m sure they have cinemas in Birmingham.’

Molly laughed. ‘Yes, of course. The Palace cinema was just up the road, on the High Street of Erdington and there were any number if you went as far as the town, and music halls and theatres, but somehow I thought—’

‘That backwards old Ireland couldn’t have such a thing; that we share our hovel with the pigs.’

‘Cathy, I never said such a thing, or thought it either.’

‘Good job too,’ Cathy said with a grin and added, ‘Some people do, you know – English people, of course. Actually, Buncrana is a thriving little place. We have factories and mills and all sorts. In fact,’ she went on, pointing down the other side of the hill to the large grey building at the bottom of it, ‘that’s the mill my father works at. We’ll go and take a look, if you like.’

‘Oh,’ Molly said as the two of them began walking down the hill past the numerous little cottages that opened on the street, ‘he doesn’t work in the post office then?’

Cathy laughed. ‘Daddy would be no great shakes in the post office; more a liability, I think, for he can’t reckon up to save his life. Mammy is going to train me up for it as soon as I am sixteen. Till then, once I leave school for good, I will man the sweet counter and deal with the papers and cigarettes. Mammy has someone to do this now but she is leaving to get married next year, which couldn’t be better timing.’

As they walked, they met others out, some standing on their doorsteps taking the air like themselves, or groups of children playing, and most had a cheery wave or greeting for the two girls. Molly felt happiness suddenly fill her being. It was the very first time she had felt this way since that dreadful day that the policeman had come to the door, and she gave a sudden sigh.

‘What’s up?’

‘Nothing, nothing at all,’ Molly said. ‘That’s why I am sighing.’

Cathy smiled at her and then said, without rancour, ‘You’re crackers, that’s what. Clean balmy.’

Molly nodded sagely. ‘I know it,’ she said. ‘It isn’t so bad if a person is aware of it.’

Cathy began to laugh, and her giggle was so infectious that Molly, who had once wondered if she would ever laugh again, joined in.

‘Did you see the faces of those we passed?’ Cathy said, when their hilarity was spent a little and she was dabbing at her damp eyes with a handkerchief. ‘If we are not careful, they will have the men with the white coats carry us away to the mental home in Derry.’

‘Rubbish,’ Molly said with a grin. ‘It made them smile too. Laughter is like that.’

‘My mammy always says it’s good for a body,’ Cathy agreed. ‘She says she had read somewhere that if you have a good belly laugh it can lengthen your life.’

‘Goodness!’ Molly said. ‘Can it really? I wonder by how much.’

‘Maybe we should have a good laugh every five minutes and live for ever,’ Cathy suggested.

‘Now, who is the fool?’ Molly smiled.

Cathy didn’t have time to answer this, for then they passed under the bridge carrying the railway line and there was the mill in front of them.

It was built on three levels, the largest of these having a tall, high chimney reaching to the sky. It didn’t look a very inspiring place to work in, but Molly reminded herself there were probably worse places in Birmingham, and she supposed that if it was work there or starve to death, one place was as inviting as the next.

‘Awful, isn’t it?’ Cathy said. ‘Daddy always said he didn’t want any of his children near the place but my brothers, John and Pat, had to work there for a bit. Then the place went afire four years ago. No one knew for a while if anyone was going to bother rebuilding it, and anyway, the boys didn’t stay around to find out. They both took the emigrant ship to America from Moville and Daddy said he didn’t blame them. They are in a place called Detroit now and, according to their letters anyway, have good jobs there in the motor industry.’

‘Didn’t your mother mind them going so far away?’ Molly asked.

Cathy nodded. ‘It was worse, of course, when my sisters left just a year after the boys to work in hotels in England. They say it is great, the hotel provides the uniforms, a place to stay and all their food, and all they need to do with their money is spend it, though they do send some home, and the boys too. It’s not the same, though. It isn’t that Mammy isn’t grateful for the money, she just says it’s hard to scrimp and scrape, working fingers to the bone raising children only for them to leave as soon as possible. She was married at seventeen, you know?’

‘Was she?’ Molly said. ‘It seems awfully young.’

‘I’ll say,’ Cathy said with feeling. ‘I certainly don’t want to go down that road at such an early age. My sisters don’t either. They say they are having too good a time to tie themselves down with a husband and weans, and that is what happens, of course, as soon as you are married. I mean, Mammy had my eldest brother, John, just ten months after they were married and he’s twenty-six now.’ She smiled and went on, ‘Mammy was glad that it was ten months. She always said the most stupid people in all the towns and villages of Ireland have the ability to count to nine.’

‘You can say that again,’ Molly said, for the girls were well aware that to have a baby outside marriage was just about the worst thing a girl could do, and to have to get married was only slightly better.

‘Anyway, Mammy hates my sisters writing so glowingly about their lives in England,’ Cathy continued. ‘She’s thinking, I suppose, that I might be tempted to join them.’

‘And are you?’

‘Not at the moment, certainly,’ Cathy said. ‘I like it here and I am set to have a good solid job helping to run the post office and probably going to take it on in the end. I don’t want to throw that in the air now, do I?’

‘Only if you were stupid,’ Molly said. ‘I really envy you to have your life so mapped out. But I will not bide here for ever. I will leave here as soon as I am old enough and be reunited with my young brother. I really miss him.’

‘Well, there in front of us is the railway station you will have to start from,’ Cathy said. ‘But you probably know that already.’

‘No. Why would I know that?’

‘Didn’t you come in there on your way from Derry?’

‘No,’ Molly told her. ‘Uncle Tom brought us home in the cart.’

‘Oh, I didn’t know that,’ Cathy said. ‘It was probably just as well, for Derry is only six miles away from here, and the trains are far from reliable. They carry freight as well, with the passengers in a sort of brake thing behind them, and of course stop at every station to unload.’

‘I would have travelled in anything at that time,’ Molly said. ‘I was so worn out. We had been on and off trains and boats since early morning.’

‘Were you sick on the crossing?’

‘I’ll say.’ Molly added with a grin, ‘It was a bit of a waste too, because we had both had breakfast on the boat and we brought it back just minutes later and everything else that had the nerve to lie in our stomachs.’

Cathy nodded, ‘My sisters said they were the same, and my younger brother, Pat, was so ill, John thought he would die on him. I bet he was more than glad to reach land, because they were at sea for ten days.’

Molly gave a shiver. ‘Poor thing,’ she said. ‘I had three and a half hours of it and that was enough.’

‘I bet,’ Cathy said with feeling. ‘Well, this now is the station. The roof looks bigger than the building. And I know where you get the tickets, because I came to see my sisters off.’ She led the way to a two-storeyed, flat-roofed building housing the ticket office, adjoining the main body of the station, and then past that and on to the platform. Molly followed and looked about her with interest. She tried to imagine the time when she would board a train from there to take her home.

‘What’s that mass of green in front?’ she asked Cathy.