По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

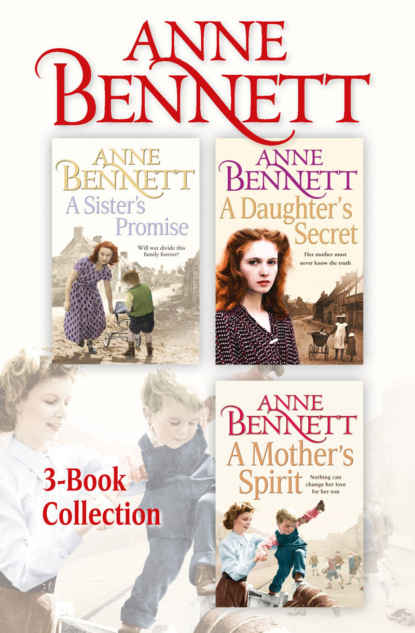

Anne Bennett 3-Book Collection: A Sister’s Promise, A Daughter’s Secret, A Mother’s Spirit

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Molly was so scared her insides were jumping about and her heart was thumping against her ribs. She knew she was going to catch it and there wasn’t anything she could do about it. She tried protesting, however. ‘I didn’t. I swear I didn’t. The priest asked me. He said—’

‘Liar!’ The punch that accompanied the word, landed square between Molly’s eyes. It knocked her from the chair on to the floor, and for a second or two she thought she had been blinded. And then she screamed as her grandmother yanked her to her feet by her hair and pounded into her again and again. Molly’s knees had buckled beneath her, but her grandmother had Molly’s hair twisted around her fingers and was holding her up as she laid into her.

A white hot fury had taken hold of Biddy and in the forefront of her mind was the picture of her husband lying dead on the floor. Each punch she levelled at Molly was because she was the daughter of the one who had caused that death and because she had gone whining to the priest. So out of control was Biddy that she wouldn’t really have cared if she killed Molly. She pummelled her face and body, ignoring her gasps of pain, the screams and cries, and eventually Molly sagged unconscious. Biddy let her fall to the floor just as Tom came in the door.

‘What have you done to her now?’ he demanded, falling to his knees by Molly’s side. It was only too obvious what had been done to her, and he could barely look down on that face as he reached across to her neck for the pulse. He sighed in relief when he felt it throbbing beneath his fingers.

But she had been so badly beaten her face was just a pulpy and bloodied mess and her eyes mere slits. Tom looked from his niece to his mother almost in disbelief. He castigated himself for leaving Molly at all to accompany the priest and then to stand chatting with him as if neither had a care in the world, while this carnage, this brutality was going on just a few yards away.

It was not the first time his mother had behaved like an untamed, out-of-control animal. His childhood had been a harsh one anyway, but there were times when his mother seemed to lose all self-control, as if a form of madness had taken over. Tom had suffered from this more than either of his brothers, and it was only the intervention of his father, often alerted by one of the others, that had sometimes prevented his mother flaying the skin from his body with the bamboo cane.

‘You deserve to be locked up, you bloody maniac,’ he ground out as he lifted Molly in his arms. ‘And it may come to that yet.’

‘Don’t you—’

‘Don’t even try talking to me,’ Tom said. ‘There are no words you could say I would want to hear. Do you know, I regret even breathing the same air as you and suggest you get to your bed and quickly, before I forget that I am your son and am tempted to give you a taste of your own medicine.’

The look in Tom’s eyes was one that Biddy had never seen before, and she decided that she might be better in bed after all. Tom lifted Molly into his arms, laid her gently on her bed, and took off her boots. His hands were tender as he bathed her face gently. But her eyes remained closed, even as he eased her dungarees from her, though he left her shirt on. Then he settled himself in the chair beside the bed for the long night ahead, determined not to leave her, lest she need something.

He watched her laboured breathing and resolved to get the doctor in if she had not recovered consciousness by the morning. His mother would kick up, but what odds whatever she did now? God Almighty, she had nearly killed the girl, and showed not a hint of remorse at what she had done. By Christ, if there was any repeat of this, or anything remotely like it, he would kill the woman with his own hands.

When Molly woke up, she felt as if she was in the pit of hell, only she couldn’t wake up, not properly, because she couldn’t open her eyes fully. Her head was pounding. She remembered the events of the evening before, and she gingerly touched her face with her fingers, feeling the cuts, grazes and bruises.

She had the acrid taste of blood in her mouth and her probing tongue found her split lips, lacerated cheeks and torn gums. She groaned and the slight sound disturbed Tom, who was in a light and uncomfortable slumber in the chair with all his clothes but his jacket still on.

‘Molly,’ he whispered, gazing at her in the light of the lamp he had left on all night. ‘How are you feeling?’

Molly shook her head and then gasped, for even such a slight movement hurt her almost unbearably and her words sounded muffled and indistinct through her damaged mouth and thick lips. ‘I hurt.’

‘Oh God,’ Tom cried. ‘I am sick to the very soul of me that this has happened to you. Sorry seems so inadequate, but I am sorry – more sorry than there are words for.’

‘I am afraid,’ Molly said.

She had been wary of her grandmother before and of the clouts, punches and slaps she would dish out, usually where Tom wouldn’t see, confident that Molly would say nothing, but the attack the previous evening had been savage. Molly had felt deep and primeval fear, for she had truly believed that Biddy had wanted to kill her, was trying to kill her.

‘Don’t be,’ Tom said. ‘Please don’t, because I promise she’ll never lay a hand on you again.’

Molly shut her eyes then, so that Tom shouldn’t see the disbelief in them and be upset, for she knew, with the best will in the world, he was no protection if his mother was bent on destroying her. He couldn’t guard her twenty-four hours a day.

The tears seeped from her eyes because she felt so helpless. Tom patted her hand, but said nothing, for he couldn’t think of any words to say that would help.

TWELVE (#ulink_662073cc-4120-5b66-93d4-3c2581cabd13)

Molly stayed in bed for four full days and Tom tended to her every need. During that time she never saw her grandmother at all, but she knew that that way of life could not continue for ever and so the fifth day, though her face still bore evidence of the attack and her body was painful and stiff, she got out of bed and was dressed when Tom came in to see how she was.

He was pleased, taking it as evidence of her improvement, though he did urge her to take it easy.

Molly shook her head. ‘It’s not the workload that worries me, Tom. It is coming face to face with your mother, but I know that it’s got to be done. I know that I can’t skulk in my room for the rest of my life.’

‘You’re right, Molly,’ Tom said. ‘And once more I admire your courage. And I’ll be right behind you, remember that.’

The knowledge should have made Molly feel better, but it didn’t and she was full of trepidation. Her mouth so dry she could barely swallow when she stepped into that room. She knew that the only way to deal with her grandmother was to stand up to her, but she didn’t know if she had the courage this time.

When she saw Biddy’s eyes slide over her face, she felt her whole body start to quiver, especially when she saw her eyes held no remorse; rather they had a gloating look about them. Biddy wasn’t sorry, not even one bit. She had felt sure that once she had the girl in Ireland she would soon lick her into shape, show her who was master, as she had her own children.

However, Molly had upended the whole house, and in her defiance and insolence had not only got Tom’s support, but the McEvoys’ and now even the priest’s. It was not to be borne. But Biddy knew this time she had thoroughly frightened the girl and she was still so full of fear that Biddy could almost smell it emanating from her.

Tom watched Molly’s reaction to his mother with worried eyes. He could well understand it. It had been that same fear that had dogged his own life and made him the soft, malleable man he was. From the arrival of Molly, his life had begun to change. For her sake he had to speak out, learn to criticise and even defy his mother sometimes and stand on his own feet more.

Molly’s tenacity had astonished him at times, yet he acknowledged this latest vicious attack had really seemed to unnerve her. Maybe it was down to him this time and so he said, ‘Haven’t you something to say to Molly, Mammy?’

Biddy’s eyes slid to those of her son. ‘I don’t think so,’ she said.

‘I was thinking of an apology, at least.’

‘There will be no apology. The girl asked for everything she got.’

‘No I did not,’ Molly yelled, sudden anger replacing her fear. ‘You hit me because you wanted to and kept on hitting me, even when I couldn’t feel it any more. You are not even human, because it isn’t normal to go on the way you did.

‘Now you listen to this,’ she went on, ‘my face is a mess and my body a mass of bruises, but they will heal, but your mind I doubt will ever be right. Next time you hit me, because the notion takes you, I just might feel like hitting you back, so I should consider that, if I were you. And you can bring the priest, bring the goddamned bishop for all I care, and I will tell them what you did to me and that it was no cold kept me from Mass and the McEvoys, which is what I gather you told them. And at least now I know exactly where I stand.’

She walked across the floor as she spoke and took her coat from the peg behind the door.

‘Where are you off to?’ Tom asked.

Molly answered, ‘I don’t really know. Just somewhere out of this house, where the air is cleaner.’

Molly followed Tom to the cowshed that evening because she refused to be left in the house with his mother, but Tom said she was to sit on the stool and watch and she was still so full of pain she was glad to do so.

He had had no chance to talk to Molly alone all day, and they had barely closed the door, when he said, ‘I couldn’t believe it the way that you stood up to Mammy today. You must have nerves of steel. You looked scared to death when you first went into that room. I thought I would have to be the one to fight for you.’

‘In my rational moments I am still scared,’ Molly said. ‘But what she said was so unjust I was incensed and that sort of overrode the fear. I never complained to the priest, Uncle Tom. He asked me all the questions and when he said he would come and talk it over with my grandmother, I was pleased. No one could have predicted that she would go off her head the way she did. I honestly didn’t know what she is capable of, how brutal she can be.’

‘The point is,’ Tom said, ‘what are we going to do about it, because there will be occasions when you are in the house together and I am nowhere around?’

‘My father said fear had to be faced head on,’ Molly said. ‘He told me that everyone is scared at some time in their lives and if you don’t learn to cope with it, then it will control you. He freely admitted he had been terrified that day he had crawled out to reach Paul Simmons. I know he would agree with my stand against your mother because she is a bully and he was always adamant that no one should let a bully win.’

‘That is all well and good, Molly, but—’

‘You are always complaining that I am too fond of that word, “but”,’ Molly said with a smile. ‘I really think your mother is not right in the head and I will never let myself be such a victim again. I imagine I could give a good account of myself if I had to.’

‘And no one would blame you,’ Tom said. ‘God! When I saw what she had done to you, I wanted to kill her. If she hadn’t got out of my sight, I really think I would have hit her and that would have been the first and only time, and changed something between us for ever.’

‘Maybe it needs changing.’

Tom shook his head. ‘Not in that way. God, I would feel even less of a man than I do already if I raised my hand to any woman, let alone my mother.’

‘I can understand that,’ Molly said. ‘Just don’t expect me to feel the same.’