По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

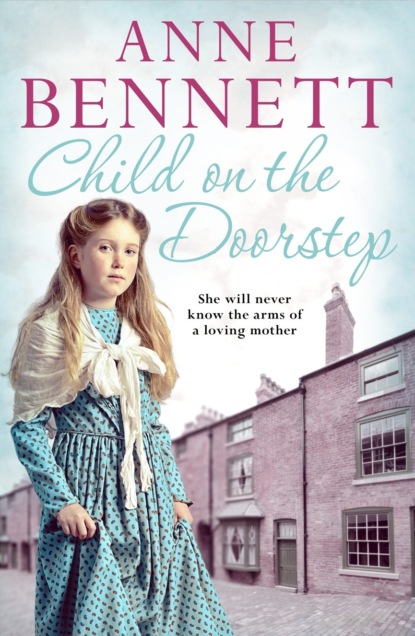

Child on the Doorstep

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Connie too had begun to rethink her life. She was coming up to thirteen now and in the senior school, and couldn’t miss the reports of the miners’ General Strike.

Now that the coal exports had fallen since the Great War, the miners’ wages were reduced from £6.00 to £3.90. The government also wanted them to work longer hours for that, and a phrase was coined that was printed in the papers:

Not a penny off the pay and not a minute on the day.

No buses, trams or trains ran anywhere, no newspapers were printed or goods unloaded from the docks, the drop forges and foundries grew silent, no coal was mined and, much to the delight of many children, schools were closed. The strike finished after nine days but little had changed and though the miners tried to hang on longer they were forced to capitulate in the end.

‘It is so sad really,’ Angela said, reading it out to her daughter from the newly printed newspaper. ‘We should be thankful we are so much better off than many.’

‘We could be better off still if you would let me leave school next year when I am fourteen and get a job like Sarah intends.’

‘Connie, we have been through all this.’

‘No, we haven’t really done that at all,’ Connie said. ‘You’ve told me what you want me to do with my life, that’s all.’

Angela frowned, for this wasn’t the way her compliant daughter usually behaved.

‘You know that going on to take your School Certificate and going on to college or university is what I’ve been saving for. What’s got into you?’

‘Nothing,’ Connie said. ‘It’s just that … Look, Mammy, if you hadn’t me to look after you would have more money. You could stop worrying about money, wipe the frown from your brow.’

‘If I’ve got a frown on my brow,’ Angela said testily, ‘it’s because I cannot understand the ungratefulness of a girl being handed the chance of a better future on a plate, which many would give their eye teeth for, and rejecting it in that cavalier way and without a word of thanks for the sacrifices I’ve made for you.’

Connie felt immediately contrite.

‘I’m sorry, Mammy,’ she said. ‘I do appreciate all you do for me and I am grateful, truly I am.’

‘I sense a “but” coming.’

‘It’s just that if I go on to matriculate I won’t fit in with the others, maybe even Sarah will think I am getting too big for my boots and …’

‘Connie, this is what your father wanted,’ Angela said and Connie knew she had lost. ‘He paid the ultimate price and fought and died to make the world a safer place for you. He wanted the best for you in all things, including education. Are you going to let him down?’

How could Connie answer that? There was only one way.

‘Of course not, Mammy. If it means so much to you and meant so much to my father, then I will do my level best to make you proud of me when I matriculate. Maybe Daddy will be looking down on me and be proud too.’

Angela gave Connie a kiss. ‘I’m sure he is, my darling girl, and I’m glad you have seen sense and we won’t have to speak of this again.’

Connie hid her sigh of exasperation and thought, as she wasn’t going to be leaving school any time soon, it was about time she started making herself more useful. She decided she would take care of her grandmother, rather than the other way round, and help her mother around the house far more.

So the next morning she slipped out of the bed she shared with Mary in the attic and, while her mother set off for work, made a pan of porridge and a pot of tea and had them waiting for Mary when she had eased her creaking body from the bed, dressed with care and stumbled stiff-legged down the stairs. She also filled a bucket with water from the tap in the yard and the scuttle with coal from the cellar and told her grandmother she would do the same every morning.

And she did and Angela was pleased at her thoughtfulness. On Monday morning Connie began rising even earlier to try to be the first one to fill the copper in the brew house with water from the tap in the yard, light the gas under it and sprinkle the water with soap suds as it heated. Then she would carry all the whites down to boil up while Angela made porridge for them all before she left for work. By the time Connie had eaten breakfast and seen to her grandmother, the whites were boiling in the copper and she would ladle the washing out with the wooden tongs into one of the sinks and empty the copper for others to use. That was as much as she could manage on school days and her mother would deal with everything else after she had finished at the pub, for lateness at school was not tolerated and all latecomers were caned.

In the holidays Connie would help her mother pound the other clothes in the maiding tub with the poss stick, or rub at persistent dirt with soap and the wash board. Then whites were put in a sink with Beckit’s Blue added, and sometimes another with starch, before everything was rinsed well, put through the mangle and pegged on lines lifted to the sky with long, long props to flap dry in the sooty air.

For all they were such a small household, it took most of the day to do the washing and most of Tuesday to do the ironing, unless of course it had rained on the Monday, in which case the damp washing would probably still be draped around the room on Tuesday, cutting off much of the heat from the fire and filling the air with steam. Connie never moaned about this because she knew it was far worse for many bigger families, like the Maguires for instance. She could only imagine the amount of clothes and bedding, towels and clothes they went through in a week, though Sarah said that was another thing that had become easier since her sisters had left home.

‘I can’t wait to do that myself either,’ Sarah said.

‘What?’

‘Leave home,’ said Sarah. ‘Siobhan and Kathy are going to keep an eye out for a job at their place and as soon as I am fourteen I’m off.’

‘Does your mother know that?’

‘Course. Only what she expected,’ Sarah said. Then she looked at Connie and said, ‘Your mammy wants you to take your School Certificate exam and go to college, don’t she?’

Angela nodded her head.

‘Do you want to?’ Sarah asked

‘No,’ Angela said. ‘I want to get out and work. All my life Mammy has worked and provided for me and Granny and I want her to take life easy for a change. If I am earning she will be able to do that. But …’ she gave a shrug, ‘she has her heart set on it. She has been to see the teacher and she says I am one of the children that could really benefit from a secondary education and so that is what she is determined I will have.’

‘How will she afford it?’

‘I asked my granny that when she first said it and Granny said all through the war when Mammy was earning good money in the munitions, every spare penny was saved for that very purpose. She said there is a tidy sum in the post office now.’

‘Is your granny for it too then?’

Angela shook her head. ‘Granny thinks no good comes of stepping out of your class.’

‘Yeah, my mother thinks that too,’ Sarah said. ‘I mean, we live here in a back-to-back house and when we marry it will likely be to someone from round here. And, as my mother says, where will your fine education get you then? And my father says there’s little point in teaching girls any more than the basics because they only get married. He said they should spend less time at school and more with their mothers learning to keep house and cook and rear babies.’

‘I can see that those things might be useful,’ Connie said. ‘But we sort of learn to do those things anyway, don’t we? And I like school.’

‘I know you do,’ Sarah said. ‘Everyone thinks you’re crazy, especially the boys.’

‘Huh, as if anyone gives a jot about what boys think or say.’

‘One day we might care a great deal,’ Sarah said, smiling broadly.

‘Maybe we will, but we’ll be older then and so will they, so it might make better sense,’ Connie said. ‘But for now I wouldn’t give tuppence for their opinion.’

‘All right but your opinion should matter,’ Sarah said. ‘Tell your mother how you feel.’

‘I can’t,’ Connie said. ‘She’d be so upset.’

She remembered how her grandmother told her how her mother would go to put more money in the post office.

‘It was all she thought about. Granny said she was even worse when she found out about the death of Barry. Mammy said the physical loss of him was one thing but she would make sure his daughter did not suffer educationally. She said she owed it to Barry to give me the best start she could. What the teacher said cemented that feeling really.’

How then could Connie throw all the plans she had made in her face? Connie was well aware of the special place she had in her mother’s heart and for that reason she couldn’t bear to hurt her. She knew she had a special place in her grandmother’s heart too and it pained her to see her growing frailer with every passing month.

‘I really don’t know what I’ll do when she’s not there any more,’ she confided to Sarah one day as they walked home from school together.

It was mid-June and the days were becoming warmer and Sarah said, ‘She is bound to rally a little now the summer is here. The winter was a long one and a bone-chilling one and, as my mother says, enough to put years on anyone.’