По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

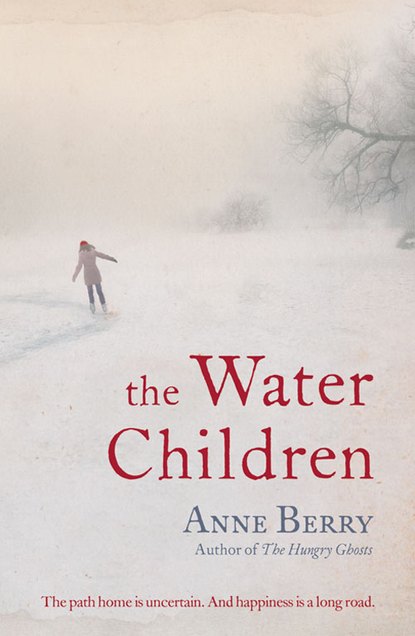

The Water Children

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

People come and crowd about them. Someone shouts that they have called an ambulance. His mother rocks to-and-fro, and eerie noises emanate from the abyss inside her, making Owen want to block his ears. The surfer keeps trying, he keeps trying to raise Lazarus; right up to the moment the medics arrive with a stretcher he is trying. Then they try too, and afterwards they put Sarah on the stretcher and hurry off to the ambulance, to try some more, they say.

It is then, as they jog up the beach looking like something out of a Charlie Chaplin film, with his father stumbling behind them reaching for his car keys in the soggy envelopes of his pockets, that his mother collapses. She seems to be eating the sand where Sarah has lain, pasting it over her face and cramming it into her mouth. And the noise that comes from her then is an inhuman roar. It commands a sea of tears to cascade from Owen’s eyes. The wind harvests them and sews them like seed diamonds in the sand. People bend over his mother and help her up as if she is an invalid. Propped between a tall man and a short woman, his rag-doll mother is dragged after his father and the ambulance men, and the stretcher with Sarah lying white as a cuttlefish and very still upon it.

The onlookers start to drift off, muttering in low voices to one another. He hears an elderly man say that he thinks they are too late, that the little girl is dead. No one seems to notice Owen. He stoops to extract Sarah’s comfort blanket from the sand, presses it to his nose and breathes through it. And there is the scent of his sister, lemony sweet and warm and sleepy. With her filling him up, he stumbles after them.

***

For Owen the best moment of the day was the very first, the glow of consciousness before he opened his eyes, before the images and sensations assailed him. But the trouble with the glow was that it ended almost before it had begun. And his bedroom was soon so crowded that there was hardly any room in it for him. It was like being on a film set, only not having a named role, just being an extra, a walk on, a bit part, absorbing the atmosphere, being careful not to upstage the real stars.

Sounds. The neat, brisk tap-tapping of footsteps in the hospital corridor, fast approaching. The pop of air rushing out of his mother when they told her. The grinding of his father’s teeth that came again and again, as if he was trying to file them down into stumps. And the shout of silence from the empty back seat as they drove home in the Hillman Husky, the silence imploring them to go back, reminding them that they had forgotten something, that they had left someone behind.

Smells. The stink of the sea, salt and mineral and washed-up dead things slowly rotting. The bitter, mothball odour of his mother’s breath for weeks afterwards, the air seeping stale and stagnant from the bleakness inside her. The fading scent of Sarah in every room of the house reminding him that she was gone, like a receding echo. The rich, heavy, fertile fragrance unleashed, of crumbling earth teeming with worms and maggots, undoing creation, as the open grave reached for his sister.

Sights. Her blithely ignorant clothes busy preparing themselves for her return, swirling around in the belly of the washing machine, waving merrily at him from the washing line, piled patiently in the ironing basket. His mother’s insistence that they be laundered, pressed, hung in her cupboard, folded neatly in her drawer. For what purpose? That they remain in readiness for Sarah’s second coming? And toys looking all lost and forlorn, as if they were clockwork and their keys were missing. Her drawing of the family taped to the kitchen cupboard, a stick daddy and mummy and Owen and Sarah, all standing in front of a square house, with the sun sending its rays in straight, uncomplicated lines to illuminate all their days. A tiny, white coffin with a brass plaque on the lid that caught the light as they lowered it into the ground, and him imagining that it was Sarah’s golden soul, that they were burying the dazzling hummingbird of Sarah’s spirit, consigning it to eternal darkness. It did not seem much bigger than the shoebox he had buried his hamster in at the beginning of the Christmas holidays, the coffin that held the remains of Sarah.

Touch. The grip of his father’s fingers digging into his shoulders at the funeral, the nails feeling like thumbtacks being driven into his flesh, the pain that made him want to be one never-ending scream. The fineness of the hairs he pulled from her brush and tucked in the pages of his bus-spotting journal, the sensation of rolling them gently between his fingers, and recalling the crowded touch of them against his bare chest that last day on the beach, almost a year ago. And the guilt, the great collar of guilt that he was yoked to, from the second he woke, with its load growing steadily heavier and heavier, until by the evening he felt like an old man who hardly had the strength to straighten up.

But today was different. He could tell straight away that he had not wet his bed, and surely this was a good sign. Just to make sure, he propped himself up on an elbow and explored under the covers with his free hand. Dry. He was dry. Perhaps today his mother would not suddenly cave in mid-sentence, imploding, deflating as if she was a punctured balloon, and groaning, that growling groan that he knew carried the cadence of death.

And all told it was not a bad day, that Saturday, not as bad as some that had gone before it. The groan did not crawl out of his mother’s gaping mouth, not in his earshot anyway. His father took the afternoon off and helped Owen to make his model Airfix Spitfire. They sat at the dining-room table with layers of newspaper spread out before them. They did not talk, except to mutter the name of the next piece they would be assembling. The newspaper crackled quietly as they went methodically about their allotted tasks. They did not touch, except once when their fingers met, sliding the tube of glue between them. They focused all their attention on the fighter plane. Owen looked forward to painting it. When it was complete he had already decided to buy another one. He had been saving up his pocket money.

His father came to tuck him in at night now. His mother only put her head round the door and blew him a kiss. She shied away from physical interaction with her son, much as his father did, but for very different reasons, Owen thought. She was scared that she might show her revulsion for the stupid boy who left Sarah alone to drown.

But then all was ruined, for that night the Merfolk came again for him. He woke and saw that his bed had become a raft, rapidly shrinking on a rough sea. He gripped the sheets, his palms damp with sweat, and felt his small craft pitch and toss under him. In his struggle there were times when the deck seemed virtually perpendicular, and he was fighting with all his might not to slide off the wall of it. At first he only glimpsed them, caught a flash of dishwater-grey, a sudden splash, the sound of hollow laughter rising like streams of bursting bubbles. He drew up his knees and pushed his face into the mattress. But even in the blackness their lantern eyes found him. When, panting for breath, he reared up and gulped in air, their webbed hands shot out of the water and grabbed at him. He gazed in horror as their spangled bodies humped and wheeled. It was as if a huge serpent was writhing about his boat bed. He peered into the depths and saw their merlocks waving like rubbery weeds in the murky swill. The water’s surface was eaten up with their scissoring fish mouths, the worm stretch of their glistening lips, the precise bite of their piranha teeth.

‘Tacka-tacka,’ they went, ‘tacka-tacka.’ And they tempted him with their honeyed promises. ‘Owen, come with us. We will teach you to swim. Ride us like sea horses. Gallop with us through an underwater world of neon blues and greens. We will juggle with sea anemones and starfish. We will dig in the silver sand for huge crabs, and trap barnacled lobsters in their lairs. We will net all day for fish and shrimp, and tie knots in the tails of slimy eels. We will surf the bow waves of blowing whales. And we will build coral castles, and play tag in gardens of kite-tailed kelp. Only, only . . . come with us.’

And he stuffed his fingers in his ears and hid under the covers, refusing to listen to any more of their lies. They did not fool him. They forgot, he already knew they had stolen his sister, drawn the shining soul out of her limp body and kept it to light the black depths they skulked in. Would they never go? Would they haunt him forever? He turned on his bedside lamp and prayed, soaked in sweat, for the visions to fade. He did not call his father to witness his shameful cowardice. He did not call his mother, because she was no longer there. But he did look at the photograph in the ebony frame that stood on his bedside table.

His father had taken it last Christmas. It was a picture of him and his mother and the snowman they had made. His mother had her arms wrapped about him and he was holding a carrot to his nose, in a fair imitation of Pinocchio. Beside them was the most magnificent snowman Owen thought he had ever seen. His chest swelled with pride knowing they had built it together, just the two of them, his mother and him. As he stared at it, his memory fast forwarded a few days, and he saw himself looking at the same snowman, tears spilling from his eyes. The sun had come out, the barometer in the porch was reading ‘Fair’, and the snow was melting. Their snowman that they had worked so hard to build, was vanishing. Then his mother was beside him, asking him what was the matter. And when he told her she said an amazing thing to him. Not only did it stop him crying, but it also made him smile. And as he remembered her words, they made him smile again. She told him that locked in the big frozen body was a child, a child made out of water, a child who pined to be free. Only when the snowman melted was the Water Child freed.

Owen’s heart was still banging like a drum and his hands were still trembling. So he closed his eyes and began to paint the melting snowman in his head. He screwed up his face with effort. He concentrated until it ached, and at last he saw him, a cymbal crash of silver light as the snowmelt dripped into the puddle. And that is when he was born, a child cut from shivering silver light, a child his mother had breathed life into, the Water Child. When Owen opened his eyes he could see him clearly, a skipping luminescence on his bedroom walls. The Merfolk, who had risen up from the sludge at the bottom of the world, who came from the heavy mud of nightmares, from the nocturnal realm of monsters too hideous to face, melted away in his presence, just as the snowman had done months ago. And although Owen’s lips remained too stiff to bend into a smile, his heart did slow and his hands became steady enough to build a model plane. And so at last he slept.

Owen didn’t want to learn to swim any more. He didn’t want his father to teach him. Swimming pools and lakes became lucid blue ogres waiting to ensnare him. As for the sea, it was a mighty pewter giant that feasted on children who wandered too near to its grimacing waves. The doctor gave a name to Owen’s terror. He told his mother that her son was an aquaphobic. ‘It is probably the result of some childhood trauma, a bad experience with the sea, perhaps? I shouldn’t press him to conquer his fear just now. In time he’s bound to grow out of it. The important thing is that there’s nothing physically wrong with him. In the meantime, I’ll write to his school asking that Owen be excused swimming lessons, for medical reasons.’ Glancing up from his notes, he gave Owen his most reassuring smile. ‘Plenty of opportunity to learn how to swim later, eh lad?’

Chapter 2

1963

A 1940s house in Kingston, South-West London, its frontage pimpled with pebbledash and painted cream. Upstairs. The smallest bedroom of three. 7 a.m. Catherine has been awake for some time. She heard the milk float and the chink of bottles on the doorstep. It is the 17th of September, her ninth birthday, and she has a plan. She stayed up late the previous night working out the details. Now her tummy is alive with thumbnail butterflies. She pictures them fluttering about in there in jerky, bright colours. Light fingers its way doggedly through the gaps in the curtains. In their bedroom across the landing she can hear her parents stirring, her mother’s high croaky voice, her father’s acquiescent teddy bear growls.

Her plan begins with a prayer. Catherine has never been very good at praying, she admits to herself now. When she goes to church with her parents, she pretends. She moves her lips in a kind of mumble and counts things in her head. How many people wearing hats? How many lighted candles? How many empty pews? In any case, she knows her mother isn’t praying properly either, she is far too preoccupied studying what the other women are wearing, making sure that she has outdone them all in, say, her new custard-yellow Orlon sweater dress, cinched in at the waist with a wide black belt, plus her matching kitten heels with the fashionable almond toes.

Deep down Catherine isn’t really sure about God, about whether he truly exists. And if, just say he does, he is really bothered with her birthday. She has her doubts, grave doubts. She thinks about all the awful things that happen in the world, like murders and aeroplane crashes, and famines with thousands of babies swelling up like plums, and terrible storms that wash away whole towns. He doesn’t do anything about them, does he? So why should he intervene on Catherine’s behalf to ensure that her day goes smoothly? If he can’t be bothered to sort out the most ghastly of life-and-death catastrophes, why on earth should he trouble himself with one girl, a shop-bought cake and a few games?

Still, she presumes that it is worth a try anyway, and it certainly won’t hurt. So she takes a deep breath, and trying to be absolutely truthful, puts real words to her prayer. She feels a bit shy (although it is only her and God, and even he might not really be present at all), so she slides down under the sheet and blankets. She clasps her hands together in the fuzzy greyness, then begins to whisper:

‘Dear God, please let today be exactly as I have imagined it. Don’t let the bad thoughts ruin it. Let Mother come into my room in a minute with a real smile on her face, not the one she usually glues there, the one that looks fixed, like a painting. And don’t let her lose her temper with me, or Father either, and shout out in that screech of hers that makes me jump inside. And don’t let him shuffle about looking all lost, making me feel embarrassed in front of my friends. Please make sure that Stephen doesn’t forget about the motorbike ride. And also, could you see to it that I get all the presents I want, and that they let me win one turn of pass the parcel, and that Penny Rainbird is so jealous of me that her face goes all red and blotchy. Amen.’

Not bad for her first real prayer, is her assessment, not bad at all. And God really seems to listen because the day gets off to a very promising start. When Catherine comes down for breakfast, her hair brushed and her mouth tingling with toothpaste, there are two parcels waiting for her on the dining table, both with cards sitting on top of them. And there are other cards too that have arrived in the post, one all the way from America that she bets is from her cousins.

‘Here she is, the birthday girl,’ her father, Keith Hoyle, says, getting up from his seat to give her a kiss on the cheek.

‘Hello, darling. Many happy returns of the day,’ her mother chimes in perfunctorily, stooping to kiss a spot in the air somewhere past her head.

‘Now, where to start, that’s the dilemma,’ he continues kindly, a twinkle in his faded blue eyes.

As he retakes his seat and Catherine sits down opposite him, her mother floats by. She is distracted by her reflection in the oval mirror. It is suspended from the picture rail above the sideboard by a brass chain. She pats her curls, then peers closer at her image, worrying that she may have spotted a couple of grey hairs tucked in among the red. Catherine, oblivious to her mother’s preening, considers grabbing the packages and ripping them open, careless of ruining the paper. But that will be wasteful and probably earn me a scolding, she cautions herself.

It is good manners to open the cards first, and besides she can’t wait to read what Uncle Christopher and Aunt Amy have to say. She has heard whispers that the American Hoyles may be coming to spend Christmas in England. The idea of seeing Rosalyn again is so exciting that she is petrified to dwell on it, in case, like a wriggling fish, it slips away. She has a presentiment that if anyone realizes how much it means to her, even God, they will maliciously sabotage the trip.

She hasn’t seen Rosalyn for, well . . . almost a year. She may have picked up an American accent by now. She wonders how they talk in Boston. And she wonders if they will recognize each other, or if they both will have altered too radically. She suspects that she is much the same. Grape-green eyes, an oval face, fine Titian hair cut short, worn with a side parting and secured with several grips. Will Rosalyn like her as much as she used to, or will a year living in America have changed her mind about her cousin, Catherine? She may find her dull now, or worse, annoying. Oh, but to spend Christmas with Rosalyn, to go to sleep with her on Christmas Eve and wake up with her on Christmas morning. She dares to believe that it is possible in a miraculous kind of way. There has definitely been talk about her family joining them, the English Hoyles joining the American Hoyles in the house they are considering renting in Sussex. To open their stockings together, and pull crackers and read the silly riddles to each other, and to sneak out for long walks, and share the secrets they have collected in the months they have been apart. Actually, Catherine can’t remember any on the spot, but given time she’s bound to come up with some. And if she does have to invent a few, Rosalyn will understand, she is certain of it.

She loves to listen to Rosalyn talk. She has a voice that is clear as glass, a voice which tings the way her mother’s best crystal tumblers do when she flicks them with her long nails. She doesn’t apologize for herself when she speaks. She isn’t at all hesitant, or ready to concede the floor if no one wants to listen. She is accustomed to people paying attention. She has a confident air that clings to her, the way clouds do to mountain peaks. And she tells wonderful stories with beautiful descriptive words, draws them with the words, and then holds up the sketches with a smile that makes Catherine melt like butter on a hot crumpet. But this is too bad, she is already letting herself think about it as if it is as good as arranged. The consequence of this sort of thing will, of course, be that it is cancelled. So she pushes it out of her head with the brute force of her own will. As a penance she will open the other cards first, make herself wait to hear the news from America. Her father clears his throat and she looks up to see his expectant face, at least, is on her.

Grandma Stubbings has sent a crisp ten-shilling note, and a card that is really too young for her, with a picture of Miss Muffet on it and a big hairy spider. And there are a couple of other cards as well, one from the godmother who hasn’t forgotten her. She has opened a savings account for Catherine and keeps telling her on birthdays and at Christmas time, that she has put in another pound. But Catherine thinks, although generous, that this is very wearisome, because she can’t take any money out until she is eighteen, which is a lifetime away. And there is a book token from her godfather who lives in Wales, and a prayer card from the lady who runs the Sunday school. Then at last she opens the one with the American stamp on it. Her Uncle Christopher and her Aunt Amy, and her cousins Rosalyn and Simon, have sent a postal order for one pound and ten shillings. Aunt Amy has written a note on the side of the card that doesn’t have a printed message on it. Catherine reads it and her heart thumps loudly in her chest.

‘Thirty shillings. That’s generous of my brother. Isn’t that kind of Christopher and Amy, Dinah?’

‘Mm . . . very generous, I’m sure. We’ll have to match it for Simon and Rosalyn, though,’ remarks Catherine’s mother, sounding less than pleased. Her brow scrunched, she picks at her hairs rather like a monkey.

‘What do they say, Catherine?’ Her father slips out his pipe to make room for the words, then plugs it back in and puffs contentedly. He will have to extinguish it in a minute, but he may as well enjoy it while this rare reprieve continues.

‘That they haven’t decided about Christmas yet. Uncle Christopher may not be able to take the time off with all the seasonal flights.’ Her father wags his head to either side in that accepting way of his. But Catherine wants to scream, to beg him, no, to beseech him on her bended knees to force his brother to come, to make a long-distance ’phone call right now and insist on it. Even if it means cancelling all the flights, then that’s what he should tell Uncle Christopher to do. Because otherwise she will die, she will simply curl up and die. But she mustn’t say that, mustn’t let on how vital it is, because then it will all be over. There won’t be one grain of hope left in the empty sack of her life. Yet, yet . . . that is the word she must hold onto. They haven’t decided yet.

With grim determination she swallows back her dismay. She will act like Elizabeth Taylor in National Velvet. She gathers up her money and postal orders now and makes a fan of them in her hand. She flutters them and pulls her lips into a smile. She is overwhelmed by her sudden wealth, but when her father questions her she has no clue what she will spend it all on. Such unexpected largesse and all those things in the shops to choose from. Her parents have given her one of the new Sindy dolls, with curly blonde hair and bold chalk-blue eyes. She is dressed in navy jeans and a red, white and blue stripy sweater. And she has two extra outfits, a glamorous pink dress for her dream dates, and an emergency ward nurse’s uniform.

‘Like it?’ her father asks. Catherine nods. She would have preferred a bike, but she hooks up the corners of her smile valiantly. Keith Hoyle glances surreptitiously at his wife, then relights his pipe which has gone out, with the mother-of-pearl lighter he always keeps in his pocket. He settles back in his chair as if he is not in any hurry at all. ‘Let’s see her done up in all her glad rags then,’ he requests. So, face radiant, Catherine dresses Sindy up in her party outfit and trots her round the crockery.

‘She’s really swinging now,’ he says, when Sindy finally stops jigging by the sugar bowl. Truly he makes Catherine want to laugh. She lets her mind run on him for a while. It is inconceivable that her father will ever be really swinging. He is thin as a beanpole, with a mournful, equine, lined face that appears sun-tanned. This is a bit of a conundrum because he is never in the sun long enough to catch its rays. His hair is very fine, the colour of a silver birch tree, clipped close around his ears and neck, parted to one side like Catherine’s. He massages brilliantine into it before combing it down, which makes it appear as if there is even less of it. It has a funny whiff about it too, rather like an old tweed coat. Her father doesn’t talk a lot either, but it isn’t noticeable because her mother prattles enough for both of them.

Stephen, Catherine’s older brother, has promised that he will call in later on, after the party. He has a job in a garage not far away. The owner lets him stay in one of the spare rooms above the business, so he returns home infrequently, and only to bring his washing or have a hot meal. Catherine thinks he resembles James Dean with his red BSA Bantam motorbike. He is saving for a Triumph Bonneville, and when he finally has enough money to buy it, he has said he will take her all the way to Brighton on it. But today, as it is her birthday, he has promised her a ride to Bushy Park and back instead. Honestly, she is more excited about this than her party, which she feels sure is bound to be a disaster.

Later, as Catherine trails through to the sitting-room to arrange her cards on the mantelpiece over the tiled fireplace, she considers her Uncle Christopher. He is a pilot, which is just about the most romantic thing in the world, she believes. He is handsome in a chiselled kind of way, while Aunt Amy has the grace of a model about her, with her wavy blonde hair, her clear skin, and her calm, low voice. There isn’t a huge gap between Rosalyn and Simon either, not like her and Stephen. Rosalyn is ten and Simon is twelve. And they talk to each other about shared interests, and watch the same programmes on the television sitting side by side. In a way Catherine is a bit frightened of Stephen. After all, he is pretty nearly an adult, and besides there is a strong scent that hangs about him, under the smell of leather and oil. It makes her feel very shy, especially on the rare occasions when she is on his bike with her arms folded about his waist, and the thrumming, dizzying whizz of the machine between her legs.

As she starts up the stairs with her presents, her mother appears in the kitchen doorway, a cigarette in her mouth, a lighter halfway to her lips. Seeing her daughter, she slips it out and wafts it in her direction. ‘You aren’t wearing that dress for the party?’ she calls after her. ‘I told you that the pale pink velvet is best. It’s hanging in the airing cupboard.’

As Catherine lifts it out, despising the fussy, lace neckline, she imagines what it must be like to be a pilot. Her father works in the city. He is a commuter with a hat, not a bowler hat but a hat anyway, and a briefcase. He trudges off to work in creased suits looking exhausted before he’s even left. And he returns grey and even more exhausted, often long after dark. Sometimes when he blows his nose black stuff comes out, which Catherine thinks is revolting, as if he isn’t just black on the outside but is slowly turning black on the inside too. He makes her think of Tom, the chimney sweep, in the book The Water Babies, as if he needs a good scrub to get the engrained dirt out of his pores. But Uncle Christopher goes to work in a smart uniform, one fit for a general or a commander or a president. They are in the back of her mind all day, her aunt, her uncle, Simon, but mostly Rosalyn, though she is determined to make the best of her party.

***

It was Christmas. They were staying in the house in Sussex with the American Hoyles. And it was every bit as amazing as she had imagined it would be. The house was huge, nearly as tall as a castle, redbrick, rectangular and solid, with lots of windows that gleamed like dozens of golden, unblinking eyes in the winter sunshine. And there was a fire-engine red front door that had a brass knocker in the shape of a face with swept-back, wild hair. When you lifted it and banged it down a couple of times it boomed satisfyingly, like a cannon firing. There were lots of bedrooms upstairs and none of them were pokey like Catherine’s. And there was an attic floor that had been converted into yet more rooms. The kitchen was massive, dominated by a milky blue Aga that crunched up scuttles full of coal every morning, while spewing out gusty exhalations of glistening dust.

The lounge was twice the size of theirs. It had wall-to-wall carpet, not just a lino floor with a rug thrown over it. There was a baronial fireplace, in which a real fire crackled and spat and hissed in the grate. It permeated the room with a homely, spicy fragrance, because of the pine logs they fed it, her uncle said. Even her mother, in a rare moment of enthusiasm engendered by the festive season, remarked that it was all rather jolly. Though she added that their built-in bar fire was definitely much cleaner, and probably a lot more efficient – cheaper too, when you con sidered the outrageous cost of fuel.

It was called ‘Wood End’, the stately house, the name painted on a sign at the bottom of the drive. Catherine’s mother admitted grudgingly that it was a suitable name, because the property actually did back onto woods. Another bonus, woods to explore and have adventures in. When they had first approached it in the grey Ford Anglia, puttering along the meandering tree-lined drive, her mother kept reminding her father that the house was only rented, that anyone could afford a house like that for a few weeks.

The property stood in enormous gardens that ran all the way round the house, with no partition dividing the front from the back. There were sweeping lawns and clusters of shrubs and lots of trees. One of them, an ancient oak, with bark like deeply wrinkled skin, only crustier, had a magical tree-house wedged in its branches, with a ladder hanging down from it. There was a separate garage, with double doors, as large as an entire house all by itself, Catherine estimated. They had brought one of the suitcases they usually took on holiday with them, Catherine cleverly sandwiching jeans and jumpers in among the dresses she so hated wearing. She had been overcome with nerves by the time they arrived, she recalled. Dry-mouthed and feeling rather sick, she had climbed out of the car as the American Hoyles piled onto the porch to meet them. This was the moment fated to sully everything, the moment Rosalyn would materialize looking incredibly grown up and aloof, surveying her cousin Catherine with a head-to-toe sweep of her crystal-blue eyes, and turning away, pained.