По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

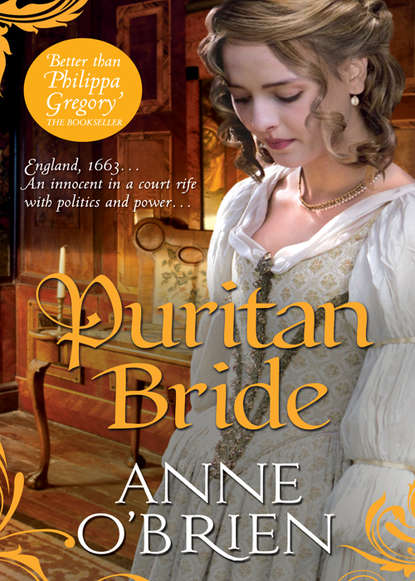

Puritan Bride

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I have to admit that the lack of candles—in the interest of economy, I presume—and the growing dusk made it difficult to pick out anything but a general impression. But she has a good figure and holds herself well. And she has a cloud of dark hair. I told her she was pretty, at any event. I am not sure that she believed me. Her opinion of me did not appear to be overly complimentary!’ He grinned at the memory of Mistress Harley’s barbed comments.

‘Oh, Marcus! You are very like your father.’

‘But is that for better or worse, my lady?’

‘I will leave that decision to you! And did you overawe the poor girl, in spite of my excellent advice, with full Court rig—nothing less than lace, velvets and those appalling shoes with red heels?’ She cast an appreciative eye over his more restrained jacket and breeches, more suitable to a country gentleman than the excesses of French fashion. The shoes in question had been abandoned for serviceable black boots.

‘My dear Mother, you could not expect me to pay my respects to my future wife in anything less.’

‘And will you go ahead with the marriage, now that you have seen Sir Henry?’

‘Why not? He is willing enough, no matter Mistress Harley’s sentiments. It brings my claim all the advantages of legitimacy. And she did not seem totally unwilling.’ He did not seem too convinced, but shrugged his shoulders. ‘I expect we shall brush along fairly well.’

Elizabeth chose not to comment, once again effectively hiding her concern on this sensitive subject. She changed tack again as Felicity, unbidden and always solicitous, poured and served small ale in pewter goblets. It sounded a bleak prospect, although Marlbrooke, lounging in an armchair before the fire, boots propped comfortably on a fire dog, appeared to be unaware.

‘Mistress Neale has told me of the occurrence last night. About the young girl you found on the road.’

Marlbrooke looked up from his contemplation of the flames. ‘Of course. I had momentarily forgotten. I am sure Mistress Neale has furnished you with all the details. You had retired when I arrived home. When I realised that she was a girl and not the young man she wished to be taken for, I asked for Mistress Neale’s help.’

‘That was very considerate of you! I believe that many would not expect it, Marcus, if gossip speaks true.’ There was a degree of disapproval in her voice.

‘My delicacy and thoughtfulness can be relied upon on such occasions.’ The gleam in his eye held a degree of cynicism not lost on his mother.

‘You could have fetched me, dear Marcus,’ Felicity interrupted with a fluttering of hands and an avid gleam in her eyes, always receptive of gossip and intrigue. ‘I believe that I was still sorting dearest Elizabeth’s embroidery silks in the small parlour. I could have come to your aid.’ Her voice was as thin and dry as her appearance. ‘There was no need for you to be concerned with some runaway girl—so indelicate, do you not think?’

‘Thank you, Felicity. I know. I suppose I did not think of it.’ And I certainly did not want you prosing in my ear about the morality of modern youth.

‘A most unsavoury circumstance, I am sure. Doubtless the girl will be recovered and well enough to leave today.’

‘Mistress Neale suggested that her head wound was quite unpleasant. And a damaged wrist, I think.’ Elizabeth closed her mind to her cousin’s perpetually querulous voice, sipped her ale thoughtfully, and directed her comment towards her son.

‘I suggest it was merely a ruse to get herself into this house,’ Felicity continued, impervious to the lack of response. ‘That type of female might sink to any level to gain the interest of her betters.’

Elizabeth sighed. ‘Are you suggesting that we should lock up the silver? I think not. If you please, Felicity, I find it rather cool in this room. Please would you be so good as to fetch me my quilted wrap from my bedchamber? I am sorry to put you out.’

‘Of course, dear Elizabeth. It is always my pleasure to be of service to you.’

‘She is so judgmental!’ Elizabeth regarded the retreating figure with disfavour. ‘And always so obsequious towards me. Sometimes I find myself wishing that she would curse me so that I could curse her back! But she never would, of course. She is far too grateful.’

‘I do not know how you tolerate her day after day. All her petty criticisms and ill wishes. Does she ever say anything pleasant about anyone?’

‘Rarely! But she helps me with all the intimate tasks that I can no longer do for myself! So I have to be grateful and tolerant.’ There was an astringent quality to her reply that her son could not ignore.

‘I know. Forgive me for my lamentable insensitivity.’

‘Besides, she has nowhere else to live. I try not to pity her or patronise her.’

‘You have more goodness than I have.’

‘So, what of the girl?’ Elizabeth asked somewhat impatiently. ‘Could she have come from the village?’

‘I think not. My impression is that she is of good family—her clothes, if a little unconventional, her hands, her features, all speak of money and breeding.’

‘Is she seriously injured?’

‘It was difficult to tell when I left her in Mistress Neale’s capable hands. She was comfortable enough and Mistress Neale had bathed and cleaned the head wound but it was deep and her face is badly bruised. We must wait. She had hacked off all her hair,’ he added inconsequentially.

Elizabeth raised her fine brows. ‘Then she won’t be pretty enough for you to flirt with!’

‘Never fear! I am now betrothed to be married and so beyond the levities of youth. And, as you know, I never flirt!’

‘Well …!’ Lady Elizabeth’s views on handsome young men who were ruthless and arrogant enough to use flattery to gain their own ends would never be known for they were interrupted by a quiet knock quickly followed by the opening of the library door. Mistress Neale entered in her usual calm fashion, hands clasped before her over her enveloping apron, the jangle of keys at her waist marking her every step. She stopped inside the door.

‘Excuse me, my lord, my lady. I have brought the young lady. She says she is recovered sufficiently to rise from her bed—although I did tell her you would understand if she rested today, in the circumstances. In my opinion, she is far from well.’

Lady Elizabeth registered the faint expression—of what, anxiety or disapproval?—on her housekeeper’s homely features, but with a mental shrug presumed that it was merely concern for the health of their unexpected guest.

‘But yes, Mistress Neale. Please come in. Is she with you now?’

Mistress Neale turned, beckoned and ushered in the young woman who had been standing in the shadows in the hall. She paused, framed by the doorway, her own ruined and unsuitable clothing discarded, now clad in ill-fitting skirt and bodice, borrowed from Elspeth, tied and tucked to take into account her slender figure. Her harshly cropped hair was uncovered. The extensive bruising down one side of her face was shocking to see, but the wound in her hair, covered by some neat bandaging, appeared to be giving her few ill effects. She held one firmly bandaged wrist awkwardly at her side. Exhaustion was printed on her face, the pallor highlighted by the plain white collar, and there was a faint frown between her brows, but she waited with apparent composure for her hostess to make the first move.

‘Come in, my poor child. What an ordeal you have been through. Come and sit with me.’ Lady Elizabeth stretched out her hand in instant compassion.

Mistress Neale curtsied and left. The lady remained standing in the doorway as if she had not heard the invitation. Viscount Marlbrooke saw the instant bewilderment in her expression and so rose and walked across the room, to take her hand. It was icy cold. She did not resist as he led her further into the room but neither did she respond to her new surroundings. His eyes searched her face, but he could detect no emotion. Perhaps she was unaware that she grasped his hand hard as he led her into the room. He felt compelled by he knew not what impulse to raise her hand and brush his lips over her rigid fingers in a formal salute.

‘There is no need to be anxious,’ he reassured her in a gentle voice as he applied a comforting pressure to her fingers. ‘I was at the crossroads and brought you here last night after the accident with your horse. I am Marcus Oxenden. This is my mother, Lady Elizabeth. You are at Winteringham Priory. Perhaps you know of it?’

Her eyes flashed to his face as she shook her head, wincing at the sudden lance of pain. If anything she became even paler, the blood draining from beneath her skin.

‘Thank you. You are very kind.’ Her voice was clear and steady but toneless as if her mind was engaged elsewhere.

‘Forgive me that I do not rise.’ Elizabeth held out her hand and smiled in welcome. ‘I find the cold weather difficult. You must tell me where you were going. I am sure that we can help you reach your destination. You must have a family—and friends—who will be concerned for you, to whom we should send a message. What is your name, my dear girl?’

The result of the concerned enquiry was devastating. It was not composure that held the girl in its rigid grasp but naked fear born out of blind panic. She pulled her hand from Marlbrooke’s light clasp to cover her face, to suppress a sob of anguish.

‘But what is wrong?’ Elizabeth struggled to gain her feet, ignoring the discomfort, moved immeasurably by the plight before her. ‘I am sure that whatever distresses you so can soon be put right.’

‘No!’

‘But what is it that causes you such despair?’ Marlbrooke raised his brows, glancing hopefully towards Lady Elizabeth, but she merely shook her head. ‘Surely it can be remedied?’

The eyes that the lady raised to Marlbrooke’s face were wide, stark with terror. ‘I don’t know where I was going,’ she explained, her voice breaking on a sob. ‘I do not know who I am. I cannot even remember my own name!’

‘I cannot remember my name,’ the lady repeated the statement in barely a whisper. ‘I don’t remember anything before I opened my eyes here this morning.’

She looked at the two strangers before her, panic turning her blood to ice, freezing her ability to assess her position with any clarity. The lady with her faded beauty, kind smile but awkward limbs. The gentleman, eyes intent, dark haired, with a distinct air of authority. Both offering compassion and support, but both total strangers. How could she be so dependent on them? She shook her head, wincing again at the sharp consequence, unable to take in her surroundings or the enormity of her predicament. In response to the mute appeal in the girl’s face, her pale lips and cheeks, Elizabeth put a gentle arm around her shoulders and steered her towards the fire. She was trembling, but obeyed as in a trance and sank to the cushioned settle. Elizabeth sat beside her, keeping possession of her hand, stroking the soft skin in comfort.

‘You must not worry so. You have had the most traumatic of experiences. You must know that you were struck on the head when you fell from your horse. I am sure your loss of memory will be temporary and you will soon remember everything quite clearly.’