По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

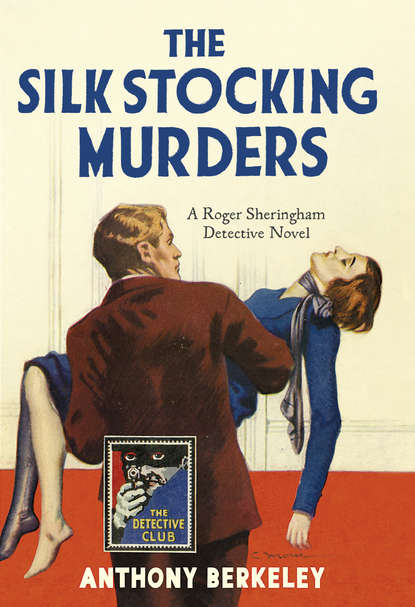

The Silk Stocking Murders

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I would,’ said Roger.

Obligingly Miss Carruthers ran off to fetch it. Returning, she opened the book at the fly-leaf and handed it to Roger. He read: ‘To my dear Janet, on her Confirmation, 14th March 1920. “Blessed are the pure in heart.”’ The writing was small and crabbed.

‘I see,’ Roger said, and took a later opportunity of slipping the book into his pocket. Miss Carruthers had definitely established the main point, at any rate.

He directed his questions elsewhere. Like Miss Carruthers, Roger had been struck with the idea that there might be a man behind things. He dredged assiduously in his informant’s mind for any clue as to his possible identity. But here Miss Carruthers was unable to help. Uny, it appeared, hadn’t cared for boys. She never went out with one alone, and would seldom consent to make up a foursome. She said frankly that boys bored her stiff. So far as Miss Carruthers knew, not only had she no particular boy, but not even any gentlemen-friends.

‘Humph!’ said Roger, abandoning that line of enquiry.

They sat and smoked in silence for a moment.

‘If you wanted to commit suicide, Miss Carruthers,’ Roger remarked abruptly, ‘would you hang yourself?’

Miss Carruthers shuddered delicately. ‘I would not. It’s the very last way I’d do it.’

‘Then why did Miss Ransome?’

‘Perhaps she didn’t realise what she’d look like,’ suggested Miss Carruthers, quite seriously.

‘Humph!’ said Roger, and they smoked again.

‘And with one of the stockings she was wearing,’ mused Miss Carruthers. ‘Funny, wasn’t it?’

Roger sat up. ‘What’s that? One of the stockings she was actually wearing?’

‘Yes. Didn’t you know?’

‘No, I didn’t see that mentioned. Do you mean,’ asked Roger incredulously, ‘that she actually took off one of the stockings she was wearing at the time, and hanged herself with it?’

Miss Carruthers nodded. ‘That’s right. A stocking on one leg, she had, and the other bare. I thought it was funny at the time. On that very door, it was; and you can still see the screw-mark the other side. The screw I took out, of course. I couldn’t have borne to look at it every time I came into the room.’

‘What screw?’ asked Roger, at sea.

‘Why, the screw on the other side of the door, that she fastened the loop to.’

‘I don’t know anything about this. I took it for granted that she’d done it on a clothes’-hook, or something like that.’

‘Well, I wondered about that,’ said Miss Carruthers, ‘but I expect it was because the hook in the bedroom was too low. And a stocking’d give a good bit, wouldn’t it?’

Roger was already out of his chair and examining the door. ‘Tell me exactly how you found her, will you?’ he said.

With many shudders, some of which may have been quite real, Miss Carruthers did so. Janet, it appeared, had been hanging on the inside of the sitting-room door, from a small hook on the other side, which had been screwed in at the right angle to withstand the strain. The stocking round her neck had been knotted together tightly at the extreme ends. As far as one could gather, she must have placed it like that loosely round her neck, then twisted the slack two or three times, and slipped a tiny loop on to the hook on the further side of the door, over the top. She had been standing on a chair to do this, and she must have kicked the chair violently away when her preparations were complete, with such force as to slam the door to, leaving herself suspended by the little hook that was now completely out of her reach, so that she could not rescue herself even had she wished. This was an obvious reconstruction on the two facts that Miss Carruthers had found the door shut when she arrived, and an overturned chair on the floor at least six feet away.

‘Good God!’ said Roger, shocked at this evidence of such cold-blooded determination on the part of the unfortunate girl to deprive herself of life. But he realised at once that this version did not square with his theory of panic-stricken impulse. Panic-stricken people do not waste time adjusting things to such a nicety, screwing in hooks at just the right height and leaving every trace of thoughtful deliberation; they simply throw themselves, as hurriedly as possible, out of the nearest window.

‘Didn’t the police think all this very odd?’ he queried thoughtfully.

‘No-o, I don’t think they did. They seemed to take it all for granted. And after all, as Uny did kill herself, it doesn’t matter much how, does it?’

Roger was forced to agree that it didn’t. But when he took his leave a few minutes later, to write that letter to Dorsetshire which must now put things beyond all hope, he was more than ever convinced that there was very, very much more in all this than had so far met the eye. And he was more than ever determined to find out just exactly what it might be.

The thought of that happy, laughing kid of the snapshot being driven into panic-stricken suicide had inexpressibly shocked him before. The thought of her now, driven into a deadly slow suicide, prepared with such tragic method and care, was infinitely more horrible. Somebody, Roger was sure, had driven that poor child into killing herself; and that somebody, he was equally sure, was going to be made to pay for it.

CHAPTER IV (#ulink_d9c3fe21-8d24-5293-8051-ba04b7118024)

TWO DEATHS AND A JOURNEY (#ulink_d9c3fe21-8d24-5293-8051-ba04b7118024)

NEVERTHELESS, during the next few days the case against the unknown made little progress. Roger received a reply to his letter from Dorsetshire which served to inflame his anxiety to get to the bottom of the affair, but his efforts in that direction seemed to be beating upon an impassable barrier. Try as he might, he could not connect Unity Ransome with any man.

He tried the theatre. Of any girl who had been at all friendly with her he asked long strings of questions, the eager Miss Carruthers constantly at his elbow. Under her protecting wing he interviewed stage-doorkeepers, stage-managers, managers, producers, stars, their male equivalents, and everybody else he could think of, till he had acquired enough theatrical copy to last him the rest of his life. But all to no purpose. Nobody could remember having seen Unity Ransome with the same man more than once or twice; to nobody had she ever mentioned the name of a male acquaintance in anything but a joking way.

He cast his net further afield. Armed with half-a-dozen pictures of Janet, enlarged from the groups outside the theatre, he sought out the restaurant-managers, waiters, tea-shop waitresses and hotel-keepers, whose various establishments Janet might have patronised. Here and there she was recognised, but it never went beyond that. Roger was discouraged.

One fact however, although it had no bearing on the subject of his search, did emerge during this busy week. Miss Carruthers having firmly appointed herself his theatrical guide and dramatic friend, Roger got into the habit of dropping in every other day or so at tea-time to report his lack of progress. The little creature with her preposterous name (she had confided by this time that her real one was Sally Briggs, ‘and what the hell,’ she asked wistfully, ‘is the use of that to me?’) both amused and interested him. It was a perpetual joy to him to watch how even in her most real moments she could not help being consciously dramatic: with genuine tears for her friend’s fate streaming down her cheeks she would yet hold them up for the admiration of an invisible gallery. In fact, Roger reflected, watching her, when she was at her most genuine, she was most artificial.

On one of these occasions he took advantage of her absence in the kitchen to study with minute care the fatal door. What he saw there upset him considerably. For it was obvious that, however anxious she might have been beforehand, when it actually came to the point Janet had not at all wanted to die. At the bottom of the door, only a few inches off the ground, was a maze of deep scratches in the paintwork, such as might have been made by a pair of high heels trying desperately to find some sort of foothold, however minute, by which to stave off eternity.

Roger’s imagination was a vivid one. He felt rather sick.

‘But why,’ he asked himself, frowning, ‘didn’t she grip the stocking above her neck and pull on that, at any rate for a few minutes? She could have been saved if she had. But I suppose there wasn’t enough of it to grip on.’

He turned his attention to the top of the door. There at the sides, and some little way down as well, were other scratches, fainter, but not to be mistaken. He walked out into the kitchen.

‘Moira,’ he said abruptly, ‘what were Unity’s nails like? Do you happen to remember?’

‘Yes,’ said Miss Carruthers, with a little shiver. ‘All broken and filled with paint and stuff.’

‘Ah!’ said Roger.

‘And she used to keep them so nice,’ said Miss Carruthers.

London having thus proved blank, Roger determined to try the country. He felt a little diffident about intruding upon the grief-stricken family, and uncertain whether to acquaint the vicar with his suspicions or not. In the end he decided not to do so until he had more evidence to support them; what he possessed already would merely add to the old man’s distress without effecting anything helpful. He trusted to his usual luck to acquire the information he wanted (if it was to be acquired) by some other means.

Having made up his mind, Roger acted with his usual impulsiveness. If he were to go at all, he would go the next day. But the next day was a Friday, and Tuesdays and Fridays were the days on which he spent the morning at The Courier offices. Very well, then; he would write his article that evening, merely call in at The Courier building to leave it and collect his post, and so catch an early train down to Dorsetshire. Excellent.

To turn out two articles a week for several months on the subject of sudden death is not, after the sixth month or so, an easy task. Having exhausted most of the topics on which he had wanted to spread himself, Roger was beginning to find the search for fresh ones getting rather too arduous. And now that he was anxious to polish one off in a hurry, of course no subject would present itself. After nibbling the end of his fountain-pen for half-an-hour, Roger ran down into the street to buy an evening paper. When inspiration fails, a newspaper will sometimes work wonders.

This one certainly came up to expectations. On the front page, in gently leaded type to show that, while startling, it could hardly be considered important, were the following headlines:

LONDON FLAT TRAGEDY

GIRL HANGS HERSELF WITH OWN STOCKING

PATHETIC LETTER

Roger was able to write a very informative article indeed, all about mass-suggestion, neurotic types, predisposition to suicide and how it is stimulated by example, and the lack of originality in most of us. ‘Within a few weeks of the first genius discovering that he could end his life by lying with his head in a gas-oven,’ wrote Roger, ‘more than a dozen had followed his lead.’ And he went on to prove that a novel method of ending life, whether one’s own or another’s, acts in such a way upon a certain type of mind that it constitutes a veritable stimulus to death. He instanced Dr Palmer and Dr Dove, Patrick Mahon and Norman Thorne, and, of course, the twin stocking tragedies. Altogether the article was in Roger’s best vein, and he was not a little pleased with it.

The next day he set off for Dorsetshire.