По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

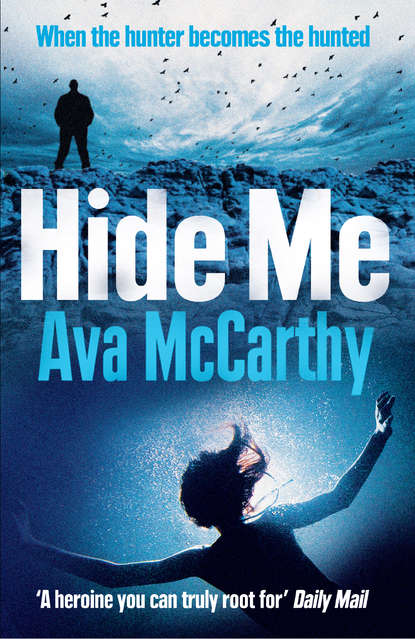

Hide Me

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Her father’s knowledge of his own ancestors was infuriatingly sketchy. He’d only lived in San Sebastián until he was ten, at which point his mother, Clara, a robust and cheerful Dubliner, had insisted on moving home in order to give her sons an Irish education.

‘At least, that’s the excuse she gave,’ Harry’s father had said, when they’d talked in Dublin a few weeks earlier. ‘If you ask me, she just wanted to escape her Basque mother-in-law.’ He’d winked at her, smiling. ‘My grandmother was a formidable woman. Aginaga, her name was. Cristos and I used to call her Dragonaga. She tried to prevent us from leaving San Sebastián, but my mother got her way in the end.’

Harry found their names on the headstone: Clara Martinez and her husband, Ramiro. Both had died before Harry was born. Far below them, she found Aginaga, who’d died at the age of ninety-four. Harry blinked. If she was reading the names and dates right, the old lady had outlived all five of her offspring. Harry felt an ache of compassion for her formidable great-grandmother. What use was longevity if it meant you saw your children die?

The only other ancestor her father remembered was his own great-grandmother, Irune. ‘She was Dragonaga’s mother-in-law. I was six when she died, and all I remember is feeling very relieved. She was terrifying. Even Dragonaga was afraid of her.’

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: