По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

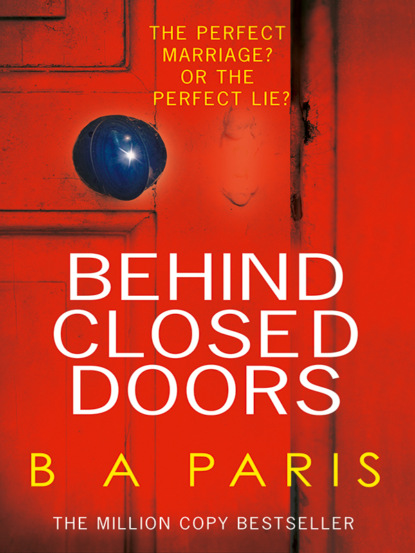

Behind Closed Doors: The gripping psychological thriller everyone is raving about

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Millie, bored with our conversation, tugged at my arm. ‘Drink, Grace. And ice cream. I hot.’

I smiled apologetically at Jack. ‘I’m afraid I have to go. Thank you again for dancing with Millie.’

‘Perhaps you would let me take you and Millie to tea?’ He leant forward so that he could see Millie sitting on the other side of me. ‘What do you think, Millie? Would you like some tea?’

‘Juice,’ Millie said, beaming at him. ‘Juice, not tea. Don’t like tea.’

‘Juice it is, then,’ he said, standing up. ‘Shall we go?’

‘No, really,’ I protested. ‘You’ve been too kind already.’

‘Please. I’d like to.’ He turned to Millie. ‘Do you like cakes, Millie?’

Millie nodded enthusiastically. ‘Yes, love cake.’

‘That’s decided then.’

We walked across the park to the restaurant, Millie and I arm in arm and Jack walking alongside us. By the time we parted company an hour later, I had agreed to meet him the following Thursday evening for dinner, and he quickly became a permanent fixture in my life. It wasn’t hard to fall in love with him; there was something old-fashioned about him that I found refreshing—he opened doors for me, helped me on with my coat and sent me flowers. He made me feel special, cherished and, best of all, he adored Millie.

When we were about three months into our relationship, he asked if I would introduce him to my parents. I was a little taken aback as I’d already told him that I didn’t have a close relationship with them. I had lied to Esther. My parents hadn’t wanted another child and, when Millie arrived, they definitely hadn’t wanted her. As a child, I had pestered my parents so much for a brother or sister that one day they had sat me down and told me, quite bluntly, that they hadn’t really wanted any children at all. So when, some ten years later, my mother discovered she was pregnant, she was horrified. It was only when I overheard her discussing the risks of a late abortion with my father that I realised she was expecting a baby and I was outraged that they were thinking of getting rid of the little brother or sister I’d always wanted.

We argued back and forth; they pointed out that because my mother was already forty-six, a pregnancy at that age was risky; I pointed out that because she was already five months pregnant, an abortion at that age was illegal—and a mortal sin, because they were both Catholics. With guilt and God on my side, I won and my mother went reluctantly ahead with the pregnancy.

When Millie was born and was found to have Down’s—as well as other difficulties—I couldn’t understand my parents’ rejection of her. I fell in love with her at once and saw her as no different from any other baby, so when my mother became severely depressed I took over Millie’s general day-to-day care, feeding her and changing her nappy before I went to school and coming back at lunchtime to repeat the process all over again. When she was three months old, my parents told me that they were putting her up for adoption and moving to New Zealand, where my maternal grandparents lived, something they had always said they would do. I screamed the place down, telling them that they couldn’t put her up for adoption, that I would stay at home and look after her instead of going to university, but they refused to listen and, as the adoption procedure got underway, I took an overdose. It was a stupid thing to do, a childish attempt to get them to realise how serious I was, but for some reason it worked. I was already eighteen so with the help of various social workers, it was agreed that I would be Millie’s principal carer and would effectively bring her up, with my parents providing financial support.

I took one step at a time. When a place was found for Millie at a local nursery, I began working part-time. My first job was working for a supermarket chain, in their fruit-buying department. At eleven years old, Millie was offered a place at a school I considered no better than an institution and, appalled, I told my parents that I would find somewhere more suitable. I had spent hours and hours with her, teaching her an independence I’m not sure she would have otherwise obtained, and I felt it was her lack of language skills rather than intelligence that made it difficult for her to integrate into society as well as she might have.

It was a long, hard battle to find a mainstream school willing to take Millie on and the only reason I managed was because the headmistress of the school I eventually found was a forward-thinking, open-minded woman who happened to have a younger brother with Down’s. The private girls’ boarding school she ran was perfect for Millie, but expensive, and, as my parents couldn’t afford to pay for it, I told them I would. I sent my CV to several companies, with a letter explaining exactly why I needed a good, well-paid job, and was eventually taken on by Harrods.

When travelling became part of my job—something I jumped at the chance to do, because of the associated freedom—my parents didn’t feel able to have Millie home for the weekends without me there. But they would visit her at school and Janice, Millie’s carer, looked after her for the rest of the time. When the next problem—where Millie would go once she left school—began to loom on the horizon, I promised my parents that I would have her to live with me so that they could finally emigrate to New Zealand. And ever since, they’d been counting the days. I didn’t blame them; in their own way they were fond of me and Millie, and we were of them. But they were the sort of people who weren’t suited to having children at all.

Because Jack was adamant that he wanted to meet them, I phoned my mother and asked her if we could go down the following Sunday. It was nearing the end of November and we took Millie with us. Although they didn’t exactly throw their arms around us, I could see that my mother was impressed by Jack’s impeccable manners and my father was pleased that Jack had taken an interest in his collection of first editions. We left soon after lunch and, by the time we dropped Millie back at her school, it was late afternoon. I had intended to head home, because I had a busy couple of days before leaving for Argentina later that week, but when Jack suggested a walk in Regent’s Park I readily agreed, even though it was already dark. I wasn’t looking forward to going away again; since meeting Jack I had become disenchanted with the amount of travelling my job required me to do as I had the impression that we hardly spent any time together. And when we did, it was often with a group of friends, or Millie, in tow.

‘What did you think of my parents?’ I asked when we had been walking a while.

‘They were perfect,’ he smiled.

I found myself frowning over his choice of words. ‘What do you mean?’

‘Just that they were everything I hoped they would be.’

I glanced at him, wondering if he was being ironic, as my parents had hardly gone out of their way for us. But then I remembered him telling me that his own parents, who had died some years before, had been extremely distant, and decided it was why he had appreciated my parents’ lukewarm welcome so much.

We walked a little further and, when we arrived at the bandstand where he had danced with Millie, he drew me to a stop.

‘Grace, will you do me the honour of marrying me?’ he asked.

His proposal was so unexpected that my first reaction was to think he was joking. Although I’d harboured a secret hope that our relationship would one day lead to marriage, I’d imagined it happening a year or two down the line. Perhaps sensing my hesitation, he drew me into his arms.

‘I knew from the minute I saw you sitting on the grass over there with Millie that you were the woman I’d been waiting for all my life. I don’t want to have to wait any longer to make you my wife. The reason I asked to meet your parents was so that I could ask your father for his blessing. I’m glad to say he gave it happily.’

I couldn’t help feeling amused that my father had so readily agreed to me marrying someone he had only just met and knew nothing about. But as I stood there in Jack’s arms, I was dismayed that the elation I felt at his proposal was tempered by a niggling anxiety, and just as I’d worked out it was because of Millie, Jack spoke again. ‘Before you give me your answer, Grace, there’s something I want to tell you.’ He sounded so serious that I thought he was going to confess to an ex-wife, or a child, or a terrible illness. ‘I just want you to know that wherever we live, there will always be a place for Millie.’

‘You don’t know how much it means to me to hear you say that,’ I told him tearfully. ‘Thank you.’

‘So will you marry me?’ he asked.

‘Yes, of course I will.’

He drew a ring from his pocket and, taking my hand in his, slipped it on my finger. ‘How soon?’ he murmured.

‘As soon as you like.’ I looked down at the solitaire diamond. ‘Jack, it’s beautiful!’

‘I’m glad you like it. So, how about sometime in March?’

I burst out laughing. ‘March! How will we be able to organise a wedding in such a short time?’

‘It won’t be that difficult. I already have somewhere in mind for the reception, Cranleigh Park in Hecclescombe. It’s a private country house and belongs to a friend of mine. Normally, he only holds wedding receptions for family members but I know it won’t be a problem.’

‘It sounds wonderful,’ I said happily.

‘As long as you don’t want to invite too many people.’

‘No, just my parents and a few friends.’

‘That’s settled then.’

Later, as he drove me back home, he asked if we could have a drink together the following evening as there were a couple of things he wanted to discuss with me before I left for Argentina on Wednesday.

‘You could come in now, if you like,’ I offered.

‘I’m afraid I really need to be getting back. I have an early start tomorrow.’ I couldn’t help feeling disappointed. ‘I’d like nothing more than to come in and stay the night with you,’ he said, noticing, ‘but I have some files I need to look over tonight.’

‘I can’t believe I’ve agreed to marry someone I haven’t even slept with yet,’ I grumbled.

‘Then how about we go away for a couple of days, the weekend after you get back from Argentina? We’ll take Millie out to lunch and after we’ve dropped her back at school, we’ll visit Cranleigh Park and find a hotel somewhere in the country for the night. Would that do?’

‘Yes.’ I nodded gratefully. ‘Where shall I meet you tomorrow evening?’

‘How about the bar at the Connaught?’

‘If I come straight from work, I can be there around seven.’

‘Perfect.’

I spent most of the next day wondering what Jack wanted to discuss with me before I went to Argentina. It never occurred to me that he would ask me to give up my job or that he would want to move out of London. I had presumed that once we were married we would carry on much as we were, except that we would be living together in his flat, as it was more central. His propositions left me reeling. Seeing how shocked I was, he sought to explain, pointing out what had occurred to me the day before, that in the three months since we’d known each other, we’d hardly spent any time together.

‘What’s the point of getting married if we never see each other?’ he asked. ‘We can’t go on as we are and, more to the point, I don’t want to. Something has to give and as I hope we’ll be having children sooner rather than later …’ He stopped. ‘You do want children, don’t you?’