По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

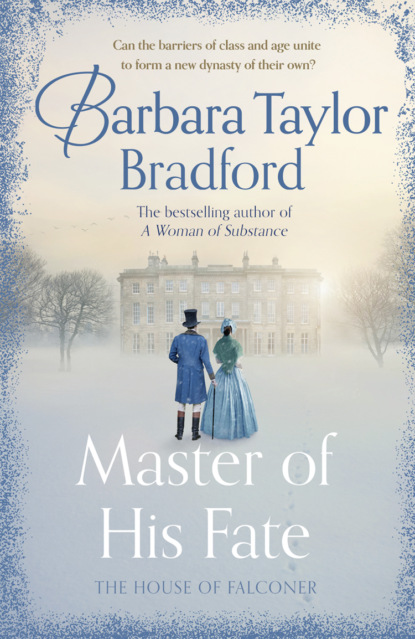

Master of His Fate: The gripping new Victorian epic from the author of A Woman of Substance

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘When you’re better, and not until then. I’ll be back in a few minutes, love.’ Esther hurried downstairs.

When she returned to the kitchen, she noticed that the bottle of raspberry vinegar and the jar of chicken soup were on the oak table. Everything else had been put away in the pantry.

‘Is Mother very ill?’ James asked, his worry obvious.

‘No, it’s just one of those bad chills, and she’s a bit chesty. But she’ll be fine. You can go up and see her if you want, or better still, you can take the drink up to her. It’ll only take a moment to boil.’

As she spoke, Esther crossed the room, picked up the bottle, and was back swiftly. Standing over a pan on the oven top, she stirred the raspberry vinegar. To this she added sugar and a large piece of butter, which James had brought to her from the pantry.

‘Is that all it is?’ James asked, sounding surprised, glancing at his grandmother. ‘Just those things boiled together?’

‘More or less,’ Esther nodded. ‘But I prepare the vinegar in a special way and put a few herbs into it as well.’

‘What are they?’

‘That’s a secret.’ Esther winked at him and poured the concoction into a cup. ‘Here it is, my lad. You can take it up to your mother. She must sip it slowly. It’s a bit hot.’

James did as he was told, and when he entered his parents’ bedroom he saw at once how poorly his mother looked. Carrying the cup carefully, he put it down on the bedside table.

Hearing the slight noise, Maude opened her eyes, and a smile surfaced when she saw her eldest son. ‘There you are, Jimmy.’

‘Grans said you’re to sip this slowly,’ he explained, reaching for the cup. ‘Be careful, Mum. ‘It’s very hot.’

Maude now pushed herself up in bed and took the cup from him. ‘I don’t know why but this is always helpful, really a good remedy for me.’

‘I think Grans put something special in it, but she wouldn’t tell me what. She said it’s a secret.’

Maude peered at him over the rim of the cup. ‘That’s strange. Your grandmother usually tells you everything.’

James chuckled. He settled back in the chair, his eyes focused on his mother. Although she looked tired and sick, he remembered his grandmother’s words that it probably was only a chill, nothing more serious. Comforted by the thought, he relaxed.

It had been a slow day at the stalls, and Matthew decided to leave early on this warm June afternoon. The market’s owner, Henry Malvern, wasn’t visiting until the next day; concern about his wife made Matthew hasten his departure, and propelled him down the Hampstead main road.

He didn’t even take the barrow with him to bring back goods tomorrow. They had plenty of stock and he had locked it away in the shed with the sawhorses and planks.

The road was full of men who were leaving the market hall and others who worked in companies or factories nearby. The road was filled to overflowing, which surprised him. It was only five o’clock. Most men worked until six or seven, some even later.

Perhaps it’s the nice weather after lots of rain, Matthew thought, as he strode out, moving at a steady pace, not wanting to start perspiring. We all want to sit in our back yards and read a newspaper, or go to the pub for a pint.

The pub. A lot of men he knew made a habit of going for a drink after work – many of them most nights of the week. He didn’t. He wanted to be in his home with his Maude and their children. They were his whole world. He wasn’t interested in swilling down beer in the taproom or playing darts, and he certainly didn’t want to listen to husbands grumbling about their wives, trying to unload their problems on him.

Maude. The image of her face came into his head, and he smiled inwardly, suddenly thinking of the first time he had set eyes on her. Eighteen years ago now.

He had been nineteen and she had been seventeen, and they had bumped into each other in the back yard at Fountains Manor in Kent.

She had explained that she was delivering a blouse for Lady Agatha when she saw him glancing at the small suitcase she was holding. He had asked to carry it for her, and she had agreed. Then he had led her to the back door, ushered her into the kitchen, where his mother happened to be speaking with Cook.

His mother obviously knew the most beautiful girl he had ever seen, had greeted her warmly, and admired the rose-pink dress she was wearing. Within seconds, she had whisked her away, taking her to Lady Agatha in her boudoir.

The sense of disappointment he had felt that day rushed back to him as he increased his pace down the road, needing to get home to be there for Maude. He recalled how he had hung around the yard until the beautiful girl had finally emerged from the house. He had asked her if he could walk her to the main gates. She had looked at him intently, questioningly, and then she had smiled and he had smiled back, floored by her beauty. Those deep brown eyes, set wide apart, full of sparkle and life under perfectly arched brows, the burnished brown hair that fell in curls around her lovely, heart-shaped face, and the slender, lithe figure. She was breathtaking.

He was smitten. And so was she.

A year later they were married. And then came the children. They were happy, loving, devoted, and extremely close, and bonded with his parents and brothers to make a dependable family unit that gave them all a sense of security.

‘I’m hungry,’ Eddie wailed. ‘Why can’t I have a sausage roll? Now!’

Rossi looked across at him and explained gently, ‘Because we’re waiting for Father, and when he gets home we can sit down and have supper together.’

‘Will Mumma get up and come down?’ Eddie asked wistfully.

‘I don’t think so, lovey. It’s better she rests.’

Eddie jumped off the chair, and said, with sudden determination, ‘I’m going upstairs to see her. I want to give her a kiss to make her feel better.’

Rossi put the knives and forks she was holding down on the table, walked across to the pantry and went inside. ‘Just this once I’ll make an exception. Please bring me one of those plates, Eddie, and I’ll give you a sausage roll to keep you going.’

Running over to the oak table, Eddie took a plate to Rossi in the pantry, a beaming smile on his face. His sister placed the roll on it, then admonished, ‘Don’t gulp it down … eat it slowly.’

‘I will.’

‘And what else do you say?’ Rossi stared at her young brother.

‘Thank you,’ Eddie replied, and carried his plate to the end of the table, far away from where Rossi was setting the places for supper.

At this moment James came back into the room, carrying the cup. ‘Mum’s fallen asleep at last. The rest will do her good.’ He took the cup to the sink, and turned to his sister. ‘I see you gave in to Eddie’s nagging. But he probably is hungry, Rossi. It’s getting late.’

‘I know, but he has to learn to be patient.’

‘I don’t want to be a patient,’ Eddie cried. ‘Then I’d be in hospital.’

‘Patient also means being able to wait for something, without making a big fuss,’ James explained, and went to sit next to the nine-year-old. ‘I could eat one of those myself, but I’ll wait till Dad gets home.’

Eddie adored his older brother, and he looked up at him and smiled, offered him the sausage roll. ‘Have a bite. I don’t mind sharing it with you, Jimmy.’

Shaking his head, James put his arm around the younger boy’s shoulders. ‘Our grandmother brought us a cottage pie and chicken soup and, as soon as Dad arrives home, we’ll tuck into it.’

Rossi exclaimed, ‘Perhaps I’d better put the pie in the oven now, Jimmy, and the chicken soup in a pan on top of the range. What do you think?’

‘That’s a good idea. Shall I help you?’

‘I’ll help, too,’ Eddie volunteered, and took a bite of the sausage roll.

‘I can manage,’ their sister answered, finally finishing the last setting. Suddenly she began to laugh as she walked back to the pantry. ‘You and Grandma brought enough food to feed Nelson’s navy. There’s also a steak and kidney pie in here, and a hunk of boiled ham. Oh, and an apple pie. Not to mention the sausage rolls.’

James laughed with her. ‘Grans kept adding things once Grandpapa had insisted we come here in a hansom.’

‘I’ve never been in one,’ Eddie said, the wistful tone echoing yet again.