По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

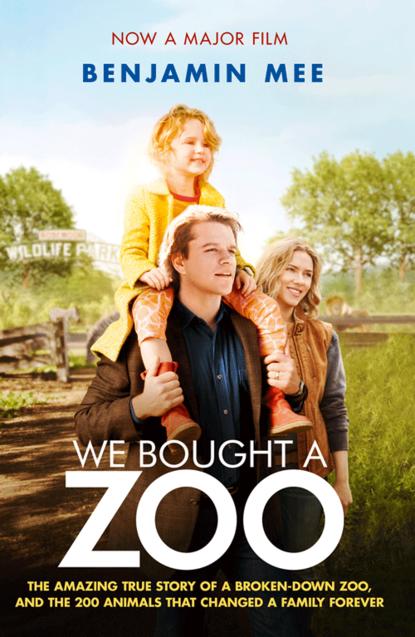

We Bought a Zoo

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

So when Katherine started getting migraines and staring into the middle distance instead of being her usual tornado of admin-crunching, packing, sorting and labelling efficiency, I put it down to stress. ‘Go to the doctor’s, or go to your parents if you’re not going to be any help,’ I said, sympathetically. I should have known it was serious when she pulled out of a shopping trip (one of her favourite activities) to buy furniture for the children’s room, and we both experienced a frisson of anxiety when she slurred her words in the car on the way back from that trip. But a few phone calls to migraine-suffering friends assured us that this was well within the normal range of symptoms for this often stressrelated phenomenon.

Eventually she went to the doctor and I waited at home for her to return with some migraine-specific pain relief. Instead I got a phone call to say that the doctor wanted her to go for a brain scan, immediately, that night. At this stage I still wasn’t particularly anxious as the French are renowned hypochondriacs. If you go to the surgery with a runny nose the doctor will prescribe a carrier bag full of pharmaceuticals, usually involving suppositories. A brain scan seemed like a typical French overreaction; inconvenient, but it had to be done.

Katherine arranged for our friend Georgia to take her to the local hospital about twenty miles away, and I settled down again to wait for her to come back. And then I got the phone call no one ever expects. Georgia, sobbing, telling me it was serious. ‘They’ve found something,’ she kept saying. ‘You have to come down.’ At first I thought it must be a bad-taste joke, but the emotion in her voice was real.

In a daze I organized a neighbour to look after the children while I borrowed her unbelievably dilapidated Honda Civic and set off on the unfamiliar journey through the dark country roads. With one headlight working, no third or reverse gear and very poor brakes, I was conscious that it was possible to crash and injure myself badly if I wasn’t careful. I overshot one turning and had to get out and push the car back down the road, but I made it safely to the hospital and abandoned the decrepit vehicle in the empty car park.

Inside I relieved a tearful Georgia and did my best to reassure a pale and shocked Katherine. I was still hoping that there was some mistake, that there was a simple explanation which had been overlooked which would account for everything. But when I asked to see the scan, there indeed was a golf-ball-sized black lump nestling ominously in her left parietal lobe. A long time ago I did a degree in psychology, so the MRI images were not entirely alien to me, and my head reeled as I desperately tried to find some explanation which could account for this anomaly. But there wasn’t one.

We spent the night at the hospital bucking up each other’s morale. In the morning a helicopter took Katherine to Montpellier, our local (and probably the best) neuro unit in France. After our cosy night together, the reality of seeing her airlifted as an emergency patient to a distant neurological ward hit home hard. As I chased the copter down the autoroute the shock really began kicking in. I found my mind was ranging around, trying to get to grips with the situation so that I could barely make myself concentrate properly on driving. I slowed right down, and arrived an hour later at the car park for the enormous Gui de Chaulliac hospital complex to find there were no spaces. I ended up parking creatively, French style, along a sliver of kerb. A porter wagged a disapproving finger at me but I strode past him, by now in an unstoppable frame of mind, desperate to find Katherine. If he’d tried to stop me at that moment I think I would have broken his arm and directed him to X-ray. I was going to Neuro Urgence, fifth floor, and nothing was going to get in my way. It made me appreciate in that instant that you should never underestimate the emotional turmoil of people visiting hospitals. Normal rules did not apply as my priorities were completely refocused on finding Katherine and understanding what was going to happen next.

I found Katherine sitting up on a trolley bed, dressed in a yellow hospital gown, looking bewildered and confused. She looked so vulnerable, but noble, stoically cooperating with whatever was asked of her. Eventually we were told that an operation was scheduled for a few days’ time, during which high doses of steroids would reduce the inflammation around the tumour so that it could be taken out more easily.

Watching her being wheeled around the corridors, sitting up in her backless gown, looking around with quiet confused dignity, was probably the worst time. The logistics were over, we were in the right place, the children were being taken care of, and now we had to wait for three days and adjust to this new reality. I spent most of that time at the hospital with Katherine, or on the phone in the lobby dropping the bombshell on friends and family. The phone-calls all took a similar shape; breezy disbelief, followed by shock and often tears. After three days I was an old hand, and guided people through their stages as I broke the news.

Finally Friday arrived, and Katherine was prepared for theatre. I was allowed to accompany her to a waiting area outside the theatre. Typically French, it was beautiful with sunlight streaming into a modern atrium planted with trees whose red and brown leaves picked up the light and shone like stained glass. There was not much we could say to each other, and I kissed her goodbye not really knowing whether I would see her again, or if I did, how badly she might be affected by the operation.

At the last minute I asked the surgeon if I could watch the operation. As a former health writer I had been in operating theatres before, and I just wanted to understand exactly what was happening to her. Far from being perplexed, the surgeon was delighted. One of the best neurosurgeons in France, I am reasonably convinced that he had high-functioning Asperger’s Syndrome. For the first and last time in our conversations, he looked me in the eye and smiled, as if to say, ‘So you like tumours too?’, and excitedly introduced me to his team. The anaesthetist was much less impressed with the idea and looked visibly alarmed, so I immediately backed out, as I didn’t want anyone involved underperforming for any reason. The surgeon’s shoulders slumped, and he resumed his unsmiling efficiency.

In fact the operation was a complete success, and when I found Katherine in the high-dependency unit a few hours later she was conscious and smiling. But the surgeon told me immediately afterwards that he hadn’t liked the look of the tissue he’d removed. ‘It will come back,’ he warned. By then I was so relieved that she’d simply survived the operation that I let this information sit at the back of my head while I dealt with the aftermath of family, chemotherapy and radiotherapy for Katherine. Katherine received visitors, including the children, on the immaculate lawns studded with palm and pine trees outside her ward building. At first in a wheelchair, but then perched on the grass in dappled sunshine, her head bandages wrapped in a muted silk scarf, looking as beautiful and relaxed as ever, like the hostess of a rolling picnic. Our good friends Phil and Karen were holidaying in Bergerac, a seven-hour drive to the north, but they made the trip down to see us and it was very emotional to see our children playing with theirs as if nothing was happening in these otherwise idyllic surroundings.

After a few numbing days on the internet the inevitability of the tumour’s return was clear. The British and the American Medical Associations, and every global cancer research organization, and indeed every other organization I contacted, had the same message for someone with a diagnosis of a Grade 4 Glioblastoma: ‘I’m so sorry.’

I trawled my health contacts for good news about Katherine’s condition which hadn’t yet made the literature, but there wasn’t any. Median survival – the most statistically frequent survival time – is nine to ten months from diagnosis. The average is slightly different, but 50 per cent survive one year. 3 per cent of people diagnosed with Grade 4 tumours are alive after three years. It wasn’t looking good. This was heavy information, particularly as Katherine was bouncing back so well from her craniotomy to remove the tumour (given a rare 100 per cent excision rating), and the excellent French medical system was fast forwarding her onto its state-of-the-art radio therapy and chemotherapy programmes. The people who survived the longest with this condition are young healthy women with active minds – Katherine to a tee. And, despite the doom and gloom, there were several promising avenues of research, which could possibly come online within the timeframe of the next recurrence.

When Katherine came out of hospital, it was to a Tardislike, empty house in an incredibly supportive village. Her parents and brothers and sister were there, and on her first day back there was a knock at the window. It was Pascal, our neighbour, who unceremoniously passed through the window a dining-room table and six chairs, followed by a casserole dish with a hot meal in it. We tried to get back to normal, setting up an office in the dusty attic, working out the treatment regimes Katherine would have to follow, and working on the book of my DIY columns which Katherine was determined to continue designing. Meanwhile, a hundred yards up the road were our barns, an open-ended dream renovation project which could easily occupy us for the next decade, if we chose. All we lacked was the small detail of the money to restore them, but frankly at that time I was more concerned with giving Katherine the best possible quality of life, to make use of what the medical profession assured me was likely to be a short time. I tried not to believe it, and we lived month by month between MRI scans and blood tests, our confidence growing gingerly with each negative result.

Katherine was happiest working, and knowing the children were happy. With her brisk efficiency she set up her own office and began designing and pasting up layouts, colour samples and illustrations around her office, one floor down from mine. She also ran our French affairs, took the children to school, and kept in touch with the stream of well-wishers who contacted us and occasionally came to stay. I carried on with my columns and researching my animal book, which was often painfully slow over a rickety dial-up internet connection held together with gaffer tape, and subject to the vagaries of France Telecom’s ‘service’, which, with the largest corporate debt in Europe, makes British Telecom seem user friendly and efficient.

The children loved the barns, and we resolved to inhabit them in whatever way possible as soon as we could, so set about investing the last of our savings in building a small wooden chalet – still bigger than our former London flat – in the back of the capacious hanger. This was way beyond my meagre knowledge of DIY, and difficult for the amiable lunch-addicted French locals to understand, so we called for special help in the form of Karsan, an Anglo-Indian builder friend from London. Karsan is a jack of all trades and master of them all as well. As soon as he arrived he began pacing out the ground and demanded to be taken to the timber yard. Working solidly for 30 days straight, Karsan erected a viable two-bedroom dwelling complete with running water, a proper bathroom with a flushing toilet, and mains electricity, while I got in his way.

With some building-site experience, and four years as a writer on DIY, I was sure Karsan would be impressed with my wide knowledge, work ethic and broad selection of tools. But he wasn’t. ‘All your tools are unused,’ he observed. ‘Well, lightly used,’ I countered. ‘If someone came to work for me with these tools I would send them away,’ he said. ‘I am working all alone. Is there anyone in the village who can help me?’ he complained. ‘Er, I’m helping you Karsan,’ I said, and I was there every day lifting wood, cutting things to order, and doing my best to learn from this multi-skilled whirlwind master builder. Admittedly, I sometimes had to take a few hours in the day to keep the plates in the air with my writing work – national newspapers are extremely unsympathetic to delays in sending copy, and excuses like ‘I had to borrow a cement mixer from Monsieur Roget and translate for Karsan at the builder’s merchants’ just don’t cut it, I found. ‘I’m all alone,’ Karsan continued to lament, and so just before the month was out I finally managed to persuade a local French builder to help, who, three-hour lunch breaks and other commitments permitting, did work hard in the final fortnight. Our glamorous friend Georgia, one of the circle of English mums we tapped into after we arrived, also helped a lot, and much impressed Karsan with her genuine knowledge of plumbing, high heels and low-cut tops. They became best buddies, and Karsan began talking of setting up locally, ‘where you can drive like in India’, with Georgia doing his admin and translation. Somehow this idea was vetoed by Karsan’s wife.

When the wooden house was finished, the locals could not believe it. One even said ‘Sacré bleu.’ Some had been working for years on their own houses on patches of land around the village, which the new generation was expanding into. Rarely were any actually finished, however, apart from holiday homes commissioned by the Dutch, German and English expats, who often used outside labour or micromanaged the local masons to within an inch of their sanity until the job was actually done. This life/work balance with the emphasis firmly on life was one of the most enjoyable parts of living in the region, and perfectly suited my inner potterer, but it was also satisfying to show them a completed project built in the English way, in back-to-back 14-hour days with a quick cheese sandwich and a cup of tea for lunch.

We bade a fond farewell to Karsan and moved in to our new home, in the back of a big open barn, looking out over another, in a walled garden where the children could play with their dog, Leon, and their cats in safety, and where the back wall was a full adult’s Frisbee throw away. It was our first proper home since before the children were born, and we relished the space, and the chance to be working on our own home at last. Everywhere the eye fell there was a pressing amount to be done, however, and over the next summer we clad the house with insulation and installed broadband internet, and Katherine began her own vegetable garden, yielding succulent cherry tomatoes and raspberries. Figs dripped off our neighbour’s tree into our garden, wild garlic grew in the hedgerows around the vineyards, and melons lay in the fields often uncollected, creating a seemingly endless supply of luscious local produce. Walking the sun-baked dusty paths through the landscape ringing with cicadas with Leon every day brought back childhood memories of Corfu where our family spent several summers. Twisted olive trees appeared in planted rows, rather than the haphazard groves of Greece, but the lifestyle was the same, although now I was a grown-up with a family of my own. It was surreal, given the backdrop of Katherine’s illness, that everything was so perfect just as it went so horribly wrong.

We threw ourselves into enjoying life, and for me this meant exploring the local wildlife with the children. Most obviously different from the UK were the birds, brightly coloured and clearly used to spending more time in North Africa than their dowdy UK counterparts, whose plumage seems more adapted to perpetual autumn rather than the vivid colours of Marrakesh.

Twenty minutes away was the Camargue, whose rice paddies and salt flats are warm enough to sustain a year-round population of flamingoes, but I was determined not to get interested in birds. I once went on a ‘nature tour’ of Mull which turned out to be a twitchers’ tour. Frolicking otters were ignored in favour of surrounding a bush waiting for something called a redstart, an apparently unseasonal visiting reddish sparrow. That way madness lies.

Far more compelling, and often unavoidable, was the insect population, which hopped, crawled and reproduced all over the place. Crickets the size of mice sprang through the long grass entertaining the cats and the children who caught them for opposing reasons, the latter to try to feed, the former to eat. At night exotic-looking, and endangered, rhinoceros beetles lumbered across my path like little prehistoric tanks, fiercely brandishing their utterly useless horns, resembling more a triceratops than the relatively svelte rhinoceros. These entertaining beasts would stay with us for a few days, rattling around in a glass bowl containing soil, wood chips, and usually dandelion leaves, to see if we could mimic their natural habitat. But they did not make good pets, and invariably I released them in the night to the safety of the vineyards.

Other nighttime catches included big fat toads, always released on to a raft in the river in what became a formalized ceremony after school, and a hedgehog carried between two sticks and housed in a tin bath and fed on worms, until his escape into the compound three days later. It was only then I discovered that these amiable but flea-ridden and stinking creatures can carry rabies. But perhaps the most dramatic catch was an unknown snake, nearly a metre long, also transported using the stick method, and housed overnight in a suspended bowl in the sitting room, lidded, with holes for air. ‘What do you think of the snake?’ I asked Katherine proudly the next morning. ‘What snake?’ she replied. The bowl was empty. The snake had crawled out through a hole and dropped to the floor right next to where we were sleeping (on the sofa bed at that time) before sliding out under the door. I hoped. Katherine was not amused, and I resolved to be more careful about what I brought into the house.

Not all the local wildlife was harmless here. Adders (lesvipères) are rife, and the brief is to call the fire brigade, or pompiers, who come ‘and dance around like little girls waving at it with sticks until it escapes’, according to Georgia who has witnessed this procedure. I once saw a vipère under a stone in the garden, and wore thick gloves and gingerly tapped every stone I ever moved afterwards. Killer hornets also occasionally buzzed into our lives like malevolent helicopter gunships, with the locals all agreeing that three stings would kill a man. My increasingly well-thumbed animal and insect encyclopedia revealed only that they were ‘potentially dangerous to humans’. Either way, whenever I saw one I adopted the full pompier procedure diligently.

But the creature that made the biggest impression early on was the scorpion. One appeared in my office on the wall one night, prompting levels of adrenaline and panic I thought only possible in the jungle. Was nowhere safe? How many of these things were there? Were they in the kids’ room now? An internet trawl revealed that 57 people have been killed in Algeria by scorpions in the last decade. Algeria is a former French colony. It’s nearby. But luckily this scorpion – dark brown and the size of the end of a man’s thumb – was not the culprit, and actually had a sting more like a bee. This jolt, that I was definitely not in London and had brought my family to a potentially dangerous situation, prompted my first (and last) poem for about twenty years, unfortunately too expletive ridden to reproduce here.

And then there was the wild boar. Not to be outdone by mere insects, reptiles and arthropods, the mammalian order laid on a special treat one night when I was walking the dog. Unusually I was out for a run, a bit ahead of Leon, so I was surprised to see him up ahead about 25 metres into the vines. As I got closer I was also surprised that he seemed jet black in the moonlight, whereas when I’d last seen him he was his usual tawny self. Also, although Leon is a hefty 8 stone of shaggy mountain dog, this animal seemed heavier, more barrel-shaped. And it was grunting, like a great big pig. I began to conclude that this was not Leon, but a sanglier, or wild boar, known to roam the vineyards at night and able to make a boar-shaped hole in a chain-link fence without slowing down. I was armed with a dog lead, a propelling pencil (in case of inspiration) and a head torch, turned off. As it faced me and started stamping the ground, I felt I had to decide quickly whether or not to turn on the head torch. It would either definitely charge at it or it would find it aversive. As the light snapped on, the grunting monster slowly wheeled round and trotted into the vines, more in irritation than fear. And then Leon arrived, late and inadequate cavalry, and shot off into the vineyards after it. Normally Leon will chase imaginary rabbits relentlessly for many minutes at a time at the merest hint of a rustle in the undergrowth, but on this occasion he shot back immediately professing total ignorance of anything amiss, and stayed very close by my side on the way back. Very wise.

The next day I took the children to track the boar, and they were wide eyed as we found and photographed the trotter prints in the loose grey earth, and had them verified by the salty farmers in the Café of the Universe in the village. ‘Il etait gros,’ they concluded, belly laughing and filling the air with clouds of pastis, when I mimicked my fear.

So, serpents included, this life was as much like Eden as I felt it was possible to get. With the broadband finally installed, and bats flying around my makeshift office in the empty barn, the book I had come to write was finally seriously under way, and Katherine’s treatment and environment seemed as good as could reasonably be hoped for. What could possibly tempt us away from this hard-won, almost heavenly niche? My family decided to buy a zoo, of course.

Chapter Two (#uc4429c63-23ed-5267-92b4-4d12985d3019)

The Adventure Begins (#uc4429c63-23ed-5267-92b4-4d12985d3019)

It was in the spring of 2005 that it landed on our doorstep: the brochure that would change our lives for ever. Like any other brochure from a residential estate agent, at first we dismissed it. But, unlike any other brochure from a residential estate agent, here we saw Dartmoor Wildlife Park advertised for the first time. My sister Melissa sent me a copy in France, with a note attached; ‘Your dream scenario.’ I had to agree with her that although I thought I was already living in my dream scenario, this odd offer of a country house with zoo attached seemed even better – if we could get it, which seemed unlikely. And if there was nothing wrong with it, which also seemed unlikely. There must be some serious structural problems in the house, or the grounds or enclosures, or some fundamental flaw with the business which was impossible to rectify. But even with this near certainty of eventual failure, the entire family was sufficiently intrigued to investigate further. A flight of fancy? Perhaps so, but it was one for which, we decided, we could restructure our entire lives.

My father, Ben Harry Mee, had died a few months before, and mum was going to have to sell the family home where they had lived for the last twenty years, a five-bedroom house in Surrey set in two acres which had just been valued at £1.2 million. This astonishing amount simply reflected the pleasant surroundings, but most importantly, its proximity to London, comfortably within the economic security cordon of the M25. Twenty-five minutes by train from London Bridge, this was the stockbroker belt, an enviable position on the property ladder achieved by my father, who, as the son of an enlightened Doncaster miner, had worked hard and invested shrewdly on behalf of his offspring all his life.

Ben did in fact work at the stock exchange for the last 15 years of his career, but not as a broker, a position which he felt could be morally dubious. Dad was Administration Controller, running the admin for the London Stock Exchange, and for the exchanges in Manchester, Dublin and Liverpool, plus a total of 11 regional and Irish amalgamated buildings. (At a similar stage in my life I was having trouble running the admin of a single self-employed journalist.) So as a family we were relatively well off, though not actually rich, and with no liquid assets to support any whimsical ventures. In 2005, the Halifax estimated that there were 67,000 such properties valued over £1,000,000 in the UK, but we seemed to be the only family who decided to cash it all in and a have a crack at buying a zoo.

It seemed like a lost cause from the beginning, but one which we knew we’d regret if we didn’t pursue. We had a plan, of sorts. Mum had been going to sell the house and downsize to something smaller and more manageable like a two- or three-bedroom cottage, then live in peace and security with a buffer of cash, but with space for only one or two offspring to visit with their various broods, at any time. The problem was, and what we all worried about, was that this isolation in old age could be the waiting room for a gradual deterioration (and, as she saw it, inevitable dementia), and death.

The new plan was to upsize the family assets and mum’s home to a 12-bedroom house surrounded by a stagnated business about which we knew nothing, but I would abandon France altogether and put my book on hold, Duncan would stop working in London, and we would then live together and run the zoo full time. Mum would be spared the daily concerns of running the zoo, but would benefit from the stimulating environment and having her family around in an exciting new life looking after 200 exotic animals. What could possibly go wrong? Come on mum … it’ll be fine.

In fact, it was a surprisingly easy sell. Mum has always been adventurous, and she likes big cats. When she was 73 I took her to a lion sanctuary where you could walk in the bush with lions, and stroke them in their enclosures, many captive bred, descended from lions rescued from being shot by farmers. I was awestruck by the lions’ size and frankly terrified, never quite able to let go of the idea that I wasn’t meant to be this close to these predators. Every whisker twitch triggered in me a jolt of adrenaline which was translated into an involuntary spasming flinch. Mum just tickled them under the chin and said, ‘Ooh, aren’t they lovely?’ The next year this adventurous lady tried skiing for the first time. So the concept of buying a zoo was not immediately dismissed out of hand.

None of us liked the idea of mum being on her own, so we were already looking at her living with one or other of us, perhaps in a larger property with pooled resources. Which is how the details of Dartmoor Wildlife Park, courtesy of Knight Frank, a normal residential estate agents in the south of England, happened to drop through mum’s letterbox. My sister Melissa was the most excited, ordering several copies of the details and sending them out to all her four brothers: the oldest Vincent, Henry, Duncan and myself. I was in France, and received my copy with the ‘Your dream scenario’ note. I had to admit it looked good, but quickly tossed it onto my teetering, soon-to-be-sorted pile. This was already carpeted in dust from the Mistral, that magnificent southern French wind which periodically blasts down the channel in south-west France created by the mountains surrounding the rivers Rhone and Soane. And then it comes right through the ancient lime mortar of my north-facing barn-office wall, redistributing the powdery mortar as a minor sandstorm of dust evenly scattered throughout the office over a period of about four days at a time. Small rippled dunes of mortar-dust appeared on top of the brochure, then other documents appeared on top of the dunes, and then more small dunes.

But Melissa wouldn’t let it lie. She wouldn’t let it lie because she thought it was possible, and had her house valued, and kept dragging any conversation you had with her back to the zoo. Duncan was quickly enthused. Having spent a short stint as a reptile keeper at London Zoo, he was the closest thing we had to a zoo professional. Now an experienced business manager in London, he was also the prime candidate for overall manager of the project, if he, and almost certainly others, chose to trade their present lifestyles for an entirely different existence.

Melissa set up a viewing for the family, minus Henry and Vincent, who had other engagements but were in favour of exploration. So it was agreed, and ‘Grandma’ Amelia, and a good proportion of her brood over three generations, arrived in a small country hotel in the South Hams district of Devon. There was a wedding going on, steeping the place in bonhomie, and the gardens, chilly in the early spring night air, occasionally echoed to stilettos on gravel as underdressed young ladies hurried to their hatchbacks and back for some essential commodity missing from the revelry inside.

A full, or even reasonably comprehensive, family gathering outside Christmas or a wedding was getting unusual, and we were on a minor mission rather than a holiday, yet accompanied by a gaggle of children of assorted ages. Our party was definitely towards the comprehensive end of the spectrum, with all that that entails. Vomiting babies, pregnant people, toddlers at Head Smash age and children accidentally ripping curtains from the wall trying to impersonate Darth Vader. The night before the viewing, we were upbeat, but realistic. We were serious contenders, but probably all convinced that we were giving it our best shot and that somebody with more money, or experience, or probably both, would come along and take it away.

We arrived at the park on a crisp April morning in 2005, and met Ellis Daw for the first time. An energetic man in his late seventies with a full white beard, and a beanie hat which he never removed, Ellis took us round the park and the house like a pro on autopilot. He’d clearly done this tour a few times before. On our quick trip around the labyrinthine 13-bedroom mansion, we took in that the sitting room was half full of parrot cages, the general decor had about three decades of catching up to do, and the plumbing and electrics looked like they could absorb a few tens of thousands of pounds to put right.

Out in the park we were all blown away by the animals, and Ellis’s innovative enclosure designs. Tiger Mountain, so called because three Siberian tigers prowl around a manmade mountain at the centre of the park, was particularly impressive. Instead of chain link or wire mesh, Ellis had adopted a ha-ha system, which basically entails a deep ditch around the inside of the perimeter, surrounded by a wall more than six feet high on the animal side, but only three or four feet on the visitor side. This creates the impression of extreme proximity to these most spectacular cats, who pad about the enclosure like massive flame-clad versions of the domestic moggies we all know and love, making you completely reappraise your relationship with the diminutive predators many of us shelter indoors.

There were lions, behind wire, but as stunning as the tigers, roaring in defiance of any other animal to challenge them for their territory, particularly other lions, apparently. And it has to be said that these bellowing outputs, projected by their hugely powerful diaphragms for a good three miles across the valley, have over the years proved 100 per cent effective. Never once has this group of lions been challenged by any other group of lions, or anything else, for their turf. It’s easy to argue that this is due to lack of predators of this magnitude in the vicinity, but one lioness did apparently catch a heron at a reputed 15 feet off the ground a few years before, confirming that this territorial defensiveness was no bluff.

Peacocks strolled around the picnic area from where you could see a pack of wolves prowling through the trees behind a wire fence. Three big European bears looked up at us from their woodland enclosure, and three jaguars, two pumas, a lynx, some flamingos, porcupines, raccoons and a Brazilian tapir added to the eclectic mix of the collection.

We were awestruck by the animals, and surprisingly not daunted at all. Even to our untutored eyes there was clearly a lot of work to be done. Everything wooden, from picnic benches to enclosure posts and stand-off barriers, was covered in algae which had clearly been there for some time. Some of it, worryingly at the base of many of the enclosure posts, was obviously having a corrosive influence. We could see it needed work, but we could also see that it had until recently been a going concern, and one which would give us a unique opportunity to be near some of the most spectacular, and endangered, animals on the planet.

As part of our official viewing of the property we were asked by a film crew from Animal Planet to participate in a documentary about the sale. The journalist in me began to wonder whether this eccentric English venture might be sustainable through another source. Writing and the media had been my career for 15 years, and, while not providing a huge amount of money, had given me a tremendous quality of life. If I could write about the things I liked doing, I could generally do them as well, and I was sometimes able to boost the activity itself with the media light which shone on it. Perhaps here was a similar model. A once thriving project now on the edge of extinction, functioning perfectly well in its day, but now needing a little nudge from the outside world to survive …

Mum, Duncan and myself were asked for the camera to stand shoulder to shoulder amongst the parrots in the living room, to explain what we would do if we got the zoo. At the end of our burst of amateurish enthusiasm, the camera man spontaneously said, ‘I want you guys to get it.’ The other offers were from leisure industry professionals with a lot of money, against whom we felt we had an outside chance, but nothing more. My scepticism was still enormous, but I began to see a clear way through, if, somehow, chance delivered it to us. Though it still felt far-fetched, like looking round all those houses my parents seemed to drag us round when we were moving house as kids; don’t get too interested, because you know you will almost certainly not end up living there.

On our tour around the park itself Ellis finally switched out of his professional spiel and looked at me, my brother Duncan, and my brother-in-law Jim, all relatively strapping lads in our early to mid-forties, and said, ‘Well, you’re the right age for it anyway.’ This vote of confidence registered with us, as Ellis had clearly seen something in us that he liked. Our ambitions for the place were modest, which he also liked. He said he’d actually turned away several offers because they involved spending too much on the redevelopment. ‘What do you want to spend a million pounds on here?’ he asked us, somewhat rhetorically. ‘What’s wrong with it? On your bike, I said to them.’ I can imagine the colour draining from his bankers’ faces when they heard this good news. Luckily we didn’t have a million pounds to spend on redevelopment – or, at this stage, even on the zoo itself – so our modest, family-based plans seemed to strike a chord with Ellis.

At about three thirty in the afternoon our tour was over and we began to notice that the excited chattering of the adults in our group was fractured increasingly frequently by minor, slightly over-emotional outbursts from our children milling around us, like progressively more manic and fractious over-wound toys. In our enthusiasm for the park we had collectively made an elementary, rookie parenting mistake and missed lunch, leading to Parents’ Dread: low blood sugar in under-tens. We had to find food fast. We walked into the enormous Jaguar Restaurant built by Ellis in 1987 to seat 300 people. Then we walked out again. Rarely have I been in a working restaurant less conducive to the consumption of food. A thin film of grease from the prolific fat fryers in the kitchen coated the tired Formica table tops, arranged in canteen rows and illuminated by harsh fluorescent strips mounted in the swirling mess of the grease-yellowed artex ceiling. The heavy scent of chip fat gave a fairly accurate indication of the menu, and mingled with the smoke of roll-ups rising from the group of staff clad in grey kitchen whites sitting around the bar, eyeing their few customers with suspicion.

Even at the risk of total mass blood-sugar implosion, we were not eating there, and asked for directions to the nearest supermarket for emergency provisions. And then, for me, the final piece of the Dartmoor puzzle fell into place, for that was when we discovered: Tesco at Lee Mill. Seven minutes away by car was not just a supermarket, but an ubermarket. In Monty Python’s Holy Grail, at the climax of the film King Arthur finally reaches a rise which gives him a view of ‘Castle Aaargh’, thought to be the resting place of the Holy Grail, the culmination of his Quest. As Arthur and Sir Bedevere are drawn across the water towards the castle by the pilotless dragon-crested ship, music of Wagnerian epic proportions plays to indicate that they are arriving at a place of true significance. This music started spontaneously in my head as we rounded a corner at the top of a small hill, and looked down into a manmade basin filled with what looked almost like a giant space ship, secretly landed in this lush green landscape. It seemed the size of Stansted Airport, its lights beaconing out their message of industrial-scale consumerism into the rapidly descending twilight of the late spring afternoon. Hot chickens, fresh bread and salad, humous, batteries, children’s clothes, newspapers and many other provisions we were lacking were immediately provided. But more importantly, wandering around its cathedral-high aisles I was hugely reassured that, if necessary, I could find here a television, a camera, an iron, a kettle, stationery, a DVD or a child’s toy. And it was open 24 hours a day. As I watched the 37 checkouts humming their queues of punters through, my final fear about relocating to the area was laid to rest. A Londoner for twenty years I had become accustomed to the availability of things like flat-screen TVs, birthday cards or sprouts at any time of the day or night, and one of the biggest culture shocks of living in southern France for the last three years had been their totally different take on this. For them, global consumerism stopped at 8.00 pm, and if you needed something urgently after that you had to wait till the next day! This Tesco, for me, meant that the whole thing was doable, and we took our picnic to watch the sunset on a nearby beach in high spirits.