По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

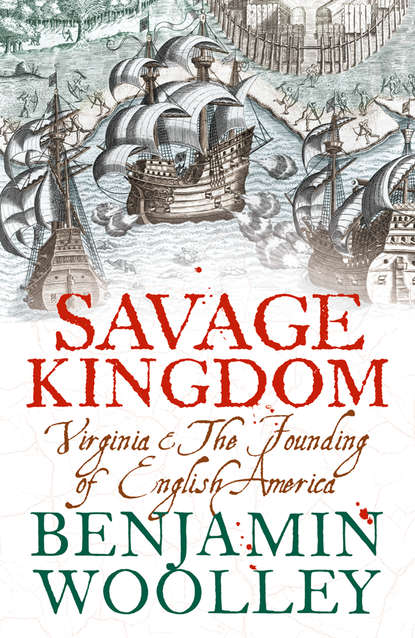

Savage Kingdom: Virginia and The Founding of English America

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

(#litres_trial_promo)

As for deciding the location of the settlement, Hakluyt recalled the experience of the Huguenots at Fort Caroline. The settlers must find ‘the Strongest most Fertile and wholesome place’ far enough upriver ‘to the end that you be not surprised as the French were in Florida’. They should also ‘in no Case Suffer any of the natural people of the Country to inhabit between You and the Sea Coast’, which might cut off their means of escape in the event of hostilities.

The settlement should be located away from heavily wooded areas, because the trees would provide cover for enemies, and they did not have the resources to clear large swathes of land (‘You shall not be able to Cleanse twenty acres in a Year’). They should also avoid a ‘low and moist place because it will prove unhealthful’. It was suggested that the best way of finding a suitably wholesome site was to look at the people who lived nearby. If they were ‘blear Eyed and with Swollen bellies and Legs’, then it was best to steer clear; if ‘Strong and Clean’ it would be a ‘true sign of a wholesome Soil’.

Once a base had been found, they were to erect a ‘little sconce’ or lookout post at the mouth of the river. The one hundred and twenty settlers were then to be split up into four groups: forty to build a fortified settlement, thirty to prepare the ground for growing ‘corn and roots’, ten to man the sconce. The remaining forty were to make up exploration parties. Gosnold was to take half of them into the interior, equipped with a compass and ‘half a Dozen pickaxes to try if they can find any mineral’. The others were to explore the river to its source, scoring the bark of trees on the river side as they went, to help search parties retrace their route should they go missing. The instructions did not specify who was to lead this mission.

Those left to construct the settlement were advised to lay out streets of ‘good breadth’ which converged on a central square or marketplace. A cannon was then to be placed in the centre, which could ‘command’ any street in the event of attack. Before setting up housing, the carpenters and ‘other suchlike workmen’ were to work on the public amenities, such as a secure storehouse and assembly room.

As for the Indians, they were recognized to be vital to the settlement’s success. ‘You must have great care not to offend the naturals if you can eschew it and employ some few of your company to trade with them for corn and all other lasting victuals.’ ‘Above all things, do not advertise the killing of any of your men’, and avoid revealing signs of sickness, in case the ‘country people’ realize the settlers are ‘but Common men’.

Trade was both crucial to survival and fraught with difficulties. The settlers should first ensure that the crews of the ships that brought them (which would soon be sailing back to England) should be prevented from having contact with local tribes, ‘for, those that mind not to inhabit [the colony], for a Little Gain will Debase the Estimation of Exchange and hinder the trade’. Before the Indians realize that the settlers mean to stay, special representatives should be appointed to barter with them for sufficient ‘Corn and all Other lasting Victuals’ to last through the first year, the settlers’ own crop to be put in store ‘to avoid the Danger of famine’.

‘The way to prosper and to Obtain Good Success’, Hakluyt concluded, ‘is to make yourselves all of one mind for the Good of your Country & your own’. Every one of them must ‘Serve & fear God the Giver of all Goodness’. They must shun corrupt or antisocial behaviour, as ‘every Plantation which our heavenly father hath not planted shall be rooted out’. Finally, they were ordered to keep all matters relating to Virginia secret, and prevent the publication of any material which did not have the Royal Council’s prior approval.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Having given their solemn oaths to abide by these orders and instructions, the three leaders of the expedition went to Blackwall to inspect the company that was to be carried across the Atlantic, and settled in the New World.

Instead of the one hundred and twenty envisaged by Hakluyt, they found around one hundred men and boys, plus a few dogs, brought for hunting and as pets.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Thirty-six of the company were identified as ‘gentlemen’, many of them the footloose younger sons of distinguished families. Anthony Gosnold was Bartholomew’s younger brother. Thomas Sandys was the younger brother of the prominent MP Edwin Sandys.

(#litres_trial_promo) Thomas Studley, the man selected to act as ‘cape merchant’ (in charge of supplies) and an enthusiastic chronicler of the coming adventure, may have come from a line of prolific writers.

(#litres_trial_promo) Kellam or Kenelm Throgmorton was probably related to Bess, the wife of Sir Walter Raleigh.

Other gentleman members of the expedition were from more obscure and modest backgrounds. Nothing is known about the origins of Robert Tyndall, the expedition navigator, beyond the fact that he was the gunner of Prince Henry, James I’s son and heir. He may have been the son of John Tyndall, who wrote in 1602 to his ‘kinsman’ Michael Hicks, Cecil’s close friend, ‘recommending him to his favour,’ but this cannot be verified.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The remainder of the company was made up of an assortment of tradesmen, labourers and young boys. While most of these ‘common sort’ were being shipped out by their masters, those with a trade or skill were contracted directly by the Virginia Company, to work for a specified period without charge, in return for their transport, tools and maintenance. The surly blacksmith James Read, and a professional mariner, Jonas Profit, probably signed up on such terms, as did Thomas Couper, a barber, Edward Brinto the stonemason, William Love the tailor, and Nicholas Skot, a drummer.

All that is known about the boys is their names: Samuel Collier, Nathaniel Pecock, James Brumfield and Richard Mutton.

(#litres_trial_promo) Some of the labourers and boys were likely to have been ‘pressed’ into service, an order from the Royal Council providing Newport with the authority to round up suitable candidates from taverns and playhouses, or buy them off gang-masters.

The fleet set sail on Saturday 20 December 1606.

(#litres_trial_promo) It was by design a low-key event. None of the government figures concerned with the venture was apparently in attendance, and whereas Elizabeth had waved off previous missions with a salute of cannon, James did not lift a hand for this departure, nor even seek to be informed.

A few days later, the ships reached the ‘Downs’, a well-known anchorage off the forelands north-east of Dover, where they awaited a favourable wind.

For weeks the fleet bobbed on the waves, while a relentless westerly whipped up the Channel, spitting sea spray and rain into the faces of the impatient captains. Every so often, a violent winter storm would throw up waves that threatened to overwhelm the ships, or drag their anchors, but, as George Percy, who was aboard the Susan Constant, loyally noted, ‘by the skilfulness of the captain [Newport] we suffered no great loss or danger’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The ships might have been unscathed, but passengers, strangers to each other’s company and many to the sea, were proving to be less resilient. Boredom and frustration soon crept into the makeshift cabins and cramped quarters. The Susan Constant, under 100 foot long and 20 foot wide, was built as a merchantman to carry cargo, not people, so her fifty or so passengers were forced either to bide their time on the freezing, gale-swept decks, or endure the claustrophobia of the airless holds below. The Godspeed, about 70 foot long and 16 foot wide, and the Discovery, 50 or so foot long and 11 foot wide, were marginally more accommodating, as both had fewer crew and proportionately more space for the passengers, but being smaller, their hulls were jolted even more violently by the churning seas.

(#litres_trial_promo)

For a month the fleet was held in this state of agitated immobility, and boredom began to breed division and distrust among the restless passengers. In particular, Edward Maria Wingfield and George Percy, who found themselves much in each other’s company, began to detect in those around them the suggestion of a religious plot, to which Robert Hunt, the mission’s chaplain, was somehow connected.

When recruiting for the voyage, Wingfield had visited the Archbishop of Canterbury on behalf of Hunt, to vouch that the cleric suited the role of vicar of Virginia as he was neither ‘touched with the rebellious humours of a popish spirit’ – a Catholic, in other words, who might be acting for the Spanish – ‘nor blemished with the least suspicion of a factious schismatic’, a religious independent, who might be tempted so far from his homeland to flout the authority of the Church of England, the bishops and the King.

(#litres_trial_promo) Now, Wingfield began to doubt his own words. Something someone had said, some slight or chance remark, suggested to him and Percy that the vicar might be blemished with a suspicion of factious schismatism after all, which threatened to defile the entire venture.

Meanwhile, another of the passengers, Captain John Smith, had formed an attachment to Hunt, nursing him through a bout of seasickness so severe that, according to Smith, ‘few expected his recovery’. During this time, the captain and the cleric fell into conversation about religious matters, and Smith found himself in close accord with Hunt’s evangelical leanings, judging him to be ‘an honest, religious, and courageous divine’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

It was at this point that Wingfield and Percy decided to confront Hunt with their suspicions. Smith, whose choleric temperament made him as quick to argue as to judge, sprang violently to his new friend’s defence, accusing these two ‘Tuftaffaty humourists’ of trying to hide their own irreligiousness.

(#litres_trial_promo)

During the ensuing row, certain rumours about Hunt’s past began to surface, like corpses from the deep. Hunt was by no means the Puritan in his own behaviour as he was now suspected of being in his religious beliefs. Three years before, he had been brought before the court of the archdeaconry of Lewes, the regional administrative body for Heathfield, to answer charges of ‘immorality’ with his servant, Thomasina Plumber. He was at the same time proceeded against for absenteeism, and there were accusations that he had neglected his congregation, leaving his friend Noah Taylor, ‘aquaebajulus’ (water bailiff or customs collector), to perform his duties.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Smith refused to believe such allegations. How could these men, ‘of the greatest rank amongst us’, circulate such ‘scandalous imputations,’ he wanted to know. They were ‘little better than Atheists’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Other passengers joined the fray, with at least three gentlemen lining up behind Smith.

(#litres_trial_promo) The argument escalated between these nascent factions until, on 12 February, it was interrupted by a change in the weather. That night, several passengers, Percy among them, clambered up to the deck to gaze into a sky that for the first time in weeks was cloudless. Percy spotted in the glistening firmament a ‘blazing star’ or comet.

The appearance of such a spectacle over the ship’s swinging mast, above a fleet trapped between deliverance into a new world and damnation in the old, was auspicious. The wind turned, and in a flurry of activity, anchors were raised, tillers spun and sails unfurled to catch it. Released from their cyclonic trap, the ships raced across the freezing waters towards the Atlantic. Within a day or so they had reached the Bay of Biscay, and soon after closed on the Canary Islands, off the coast of Morocco.

The six-week delay in the Downs had meant their provisions for the voyage had already been used up, forcing them to break into supplies set aside for their first months in America. So they decided to stop at the Canaries and spend what money they could to make up the deficit.

As soon as the ships dropped anchor, the rows resumed. According to one report, some of the passengers, including one Stephen Calthorp, a gentleman from a prominent Norfolk family, now joined Smith in threatening mutiny.

(#litres_trial_promo) At this point, Newport lost patience, and ordered the ringleader Smith to be ‘committed a prisoner’ in the belly of the Susan Constant, Smith’s furious indignation muffled by the heaps of bulging sacks that furnished his cell, and the layers of sturdy oak decking that would wall him in for the coming weeks.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Picking up the trade winds, the fleet headed off into the Atlantic, covering over 3,000 miles in six weeks. The freezing temperatures of a European winter melted into the sultry warmth of the tropics, providing Percy with some hope of respite from his attacks of epilepsy.

On 23 March, they had their first sight of the West Indies, passing Martinique before reaching Dominica, ‘a very fair island, the trees full of sweet and good smells’. The island was inhabited by ‘many savage Indians’, who at first kept their distance. As soon as they realized that the European visitors were not Spanish, the mood changed, and ‘there came many to our ships with their canoes, bringing us many kinds of sundry fruits, as pines [pineapples], potatoes, plantains, tobacco, and other fruits’. After weeks of dried biscuits and salted meat, the men consumed the gifts greedily. They also happily accepted an ‘abundance’ of fine French linen, which the Indians had salvaged from Spanish ships that had been wrecked on the island.

The English gave the Indians knives and hatchets, ‘which they much esteemed’, and beads, copper and jewels, ‘which they hang through their nostrils, ears, and lips – very strange to behold’. During the transactions, the English learned that the natives had suffered a ‘great overthrow’ at the hands of the Spanish, which explained their initial wariness and subsequent generosity.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The encounter provided a useful introduction to developing relations with locals, and confirmed English assumptions of Spanish barbarism – the infamous ‘Black Legend’ or leyenda negra. The legend had its origins in A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies, a furious indictment of Spanish imperialism written by a Spanish bishop, Bartolomé de las Casas. It had been translated into English in 1583 ‘to serve as a precedent and warning to the twelve provinces of the Low Countries’.