По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

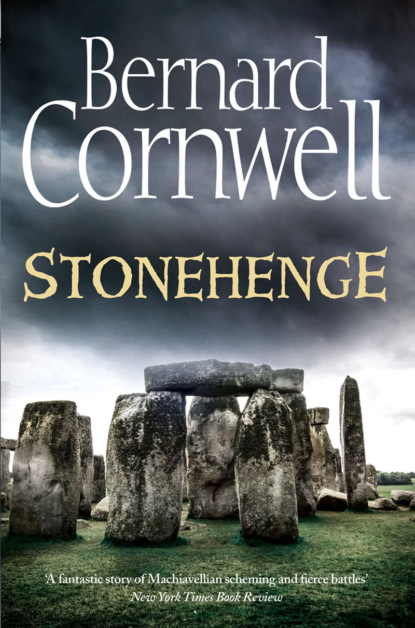

Stonehenge: A Novel of 2000 BC

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘It does look beautiful,’ Galeth agreed. It was Galeth, practical, strong and efficient, who would have to raise the stones, and he tried to imagine how the eight great boulders would look in that clean setting of grass and chalk. ‘Slaol will be pleased,’ he decided.

There was thunder that night, but no rain. Just thunder, far off, and in the darkness two of the tribe’s children died. Both had been sick, though no one had thought they would die. But in the morning the sun rose to make the newly cleared chalk-ring shine, and the gods, folk reckoned, were once again smiling on Ratharryn.

Derrewyn was not yet a woman, but it was a custom in both Ratharryn and Cathallo that betrothed girls would live with their prospective husband’s family, so Derrewyn came to Ratharryn to live in the hut of Hengall’s oldest surviving wife.

Her arrival disturbed the tribe. She might be a year from womanhood, but her beauty had blossomed early and the young warriors of Ratharryn stared at her with undisguised yearning, for Derrewyn of Cathallo was a girl to stir men’s dreams. Her black hair hung below her waist and her long legs were tanned dark by the sun. About her ankles and her neck she wore delicate chains of pure white sea-shells, all the shells alike and of a size. Her eyes were dark, her face was slender and high-boned, and her spirit as quick as a kingfisher’s flight. The young warriors of Hengall’s tribe noted her, watched her, and reckoned she was too good for Saban who was still only a child. Hengall, seeing their desire, ordered Gilan to work a protective charm on the girl, so the high priest placed a human skull on the roof of Derrewyn’s hut and beside it he put a phallus of unfired clay and every man who saw the charm understood its threat. Touch Derrewyn without permission, the skull and phallus said, and you will die, and from that time the men looked, but did nothing more.

Saban also looked and yearned, and some in the tribe noted how Derrewyn gazed back at Saban, for he was promising to be a handsome man. He was still growing, but already he was as tall as his father and he had all Lengar’s quickness of eye and hand. He was accurate with a yew bow, was one of the fastest runners in the tribe and yet was modest, calm-tempered and well liked in Ratharryn. He promised to be a good man, but if he failed his ordeals he would never be reckoned an adult, so, in the months after his first meeting with Derrewyn, he was kept busy learning the secrets of the woods and the ways of the beasts. He watched the stags fighting and rutting, found where the otters had their dens and learned how to steal honey from irate bees. He was not allowed to sleep in the woods for he was still a child, but he killed his first wolf in early winter, felling it with a well-aimed arrow and ending the wounded beast’s life with a blow of a stone axe. Galeth’s woman, Lidda, pierced the wolf’s claws and threaded them on a sinew, then gave the necklace to Saban.

Saban might have been the son of the chief, but he was expected to work like everyone else. ‘A man who does nothing,’ Hengall liked to say, ‘eats nothing.’ Galeth was the tribe’s best woodworker, and for seven years Saban had been learning his uncle’s trade. He had learned all the names of the tree gods and how to placate them before an axe was laid to a trunk, and he had learned how to shape oak and ash into beams, posts and rafters. Galeth taught him how to make an adze blade from flint, and how to tie it to the haft with wet oxhide strips that shrank tight so that the head did not loosen during work. Saban was allowed to use flint tools, but neither he nor Galeth’s son, who had been born to Galeth’s first wife, were ever permitted to touch the two precious bronze axes that had been carried long distances across the land and had cost Galeth dearly in pigs and cattle.

Saban learned to carve beechwood into bowls and willow into paddles. He learned how to whittle a branch of stone-hard yew wood into a deer-killing bow. He learned to joint wood, and how to auger it with spikes of flint, bone or holly. He learned how to take an elm trunk and shape it into a hollow boat that could float all the way down the river to the sea and bring back bags of salt, shells and dried fish. He learned how to peg green oak so that it shrank into place, and he learned well, for in the winter before Saban’s ordeals Galeth trusted him to raise a new roof on the hut where Derrewyn slept.

Saban stripped the rotting thatch, but first handed the skull down to Derrewyn who, knowing that it protected her, kissed its forehead and then looked up at Saban. ‘And the rest,’ she said, smiling.

‘The rest?’

‘The clay,’ she said. The unfired clay phallus had crumbled in the weather, but Saban collected what he could from among the rotting thatch and gave it to her. She grimaced at the dirty scraps of clay, but found one fragment that was cleaner than the rest and reached up to give it back to Saban. ‘Swallow it,’ she ordered him.

‘Swallow it?’

‘Do it!’ she insisted, then laughed at his expression as he forced the lump down his throat.

‘Why did I do that?’ Saban asked her, but she just laughed and then the laugh faded as Jegar came round the hut’s corner.

Jegar was now the tribe’s best hunter. He went into the forest for days, leading a band of young men who brought back carcasses and tusks. There were some in the tribe who believed Jegar should succeed Hengall, for it was plain the gods favoured him, though if Jegar shared that opinion he showed no sign of it. Instead he was respectful to Hengall and took care to offer the chief the best cuts of meat from his kill and Hengall, in turn, dealt cautiously with the man who had once been Lengar’s closest companion.

Jegar now stared at Derrewyn. Like the other men of the tribe he had been deterred by the skull on her roof, but he could not hide his longing for her, nor his jealousy of Saban. In the new year, when Saban undertook the ordeals of manhood, he would be hunted in the deep forest and all the tribe knew that Jegar and his hounds would be on Saban’s trail. And if Saban failed, then Saban could not marry.

Jegar smiled at Derrewyn who clutched the skull to her breasts and spat. Jegar laughed, then licked his spear blade and pointed it at Saban. ‘Next year, little one,’ he said, ‘we shall meet in the trees. You, me, my hunting companions and my hounds.’

‘You need friends and hounds to beat me?’ Saban asked. Derrewyn was watching him and her gaze made him reckless. ‘Tell me about next year, Jegar,’ he said. He knew it was dangerously foolish to taunt Jegar, but he feared Derrewyn would despise him if he meekly allowed Jegar to bully him. ‘What will you do if you catch me in the forest?’ he demanded, jumping down to the ground.

‘Thrash you, little one,’ Jegar said.

‘You don’t have the strength,’ Saban said, and he picked up a long ash pole that was used to measure the lengths of the replacement rafters. He was taller than Jegar, and he also knew that Jegar would not dare kill him here in the settlement where so many were watching, but he was still risking a painful beating. ‘You couldn’t thrash a kitten,’ he added scornfully.

‘Go back to work, boy,’ Jegar said, but Saban just slashed the pole at him, making the smaller man step back. Saban slashed again, and the clumsy weapon whipped past Jegar’s face. This time the hunter snarled and levelled his spear. ‘Careful,’ he said.

‘Why should I be careful of you?’ Saban asked. Fear and exhilaration were competing in him. He knew this was stupidity, but Derrewyn’s presence had driven him to it and his own pride would not let him back down. ‘You’re a bully, Jegar,’ he said, drawing back the pole, ‘and I’ll thrash you bloody.’

‘You child!’ Jegar said, and ran at Saban, but Saban had guessed what Jegar would do and he let the pole’s tip fall so that it tangled Jegar’s legs, and then he twisted the pole, tripping Jegar, and as Jegar fell Saban jumped on him and beat his enemy’s head with his fists. He landed two hard blows before Jegar managed to twist round and lash back. Jegar could not use his spear for Saban was on top of him, so first he tried to punch the boy away, then he clawed at Saban’s eyes. Saban bit one of the probing fingers and tasted blood, then hands seized and dragged him off Jegar. Other hands pulled Jegar away.

It was Galeth who had hauled Saban away. ‘You fool!’ Galeth said. ‘You want to die?’

‘I was beating him!’

‘He’s a man. You’re a boy! And you’re going to have a black eye.’ Galeth pushed Saban away, then turned on Jegar. ‘Leave him alone,’ he ordered. ‘Your chance comes next year.’

‘He attacked me!’ Jegar said. His hand was bleeding where Saban had bitten it. He sucked at the blood, then picked up his spear. There was rage in his eyes, for he knew he had been humiliated. ‘A boy who attacks a man has to be punished,’ he insisted.

‘No one attacked anyone,’ Galeth said. He was huge, and his anger was frightening. ‘Nothing happened here. You hear me? Nothing happened!’ He drove Jegar back. ‘Nothing happened!’ He turned on Derrewyn who had watched the fight with wide eyes. ‘Be about your work, girl,’ he ordered, then pushed Saban back to the roof. ‘And you’ve got work to do, so do it.’

Hengall chuckled when he heard about the fight. ‘Was he really winning?’ he asked Galeth.

‘He wouldn’t have lasted,’ Galeth said, ‘but yes, he was winning.’

‘He’s a good boy,’ Hengall said approvingly, ‘a good boy!’

‘But Jegar will try to stop him passing the ordeals,’ Galeth warned.

Hengall dismissed his younger brother’s fears. ‘If Saban is to be chief,’ he said, ‘then he must be able to deal with men like Jegar.’ He chuckled again, delighted that Saban had shown such courage. ‘You’ll keep an eye on the boy through the winter?’ he asked. ‘He deserves better than to be speared in the back.’

‘I shall watch him,’ Galeth promised grimly.

It proved a cruelly hard winter, and the only good news of that cold season was that the warriors of Cathallo abandoned their raids on Hengall’s land. The peace, which would be sealed by Saban’s marriage, was holding, though some folk reckoned Cathallo was just waiting for Hengall’s death before snapping up Ratharryn as they had conquered Maden. Others reckoned that it was the weather that kept Kital’s men at bay, for the snow lay thick for days and the river froze so that the women had to break the ice to fetch their daily water. There were days when the snow on the hills blew from the low crests like smoke, when the fires seemed to give no warmth and the ice-bound huts crouched in a grey-white land that offered no hope of warmth or life. The weak of the tribe, the old, the young, the sick and the cursed, died. There was hunger, but the warriors of the tribe hunted in the forests. None rivalled Jegar and his band who, day after day, brought back carcasses that were butchered outside the settlement where the guts steamed in the cold air as the tribe’s dogs circled in hope of spoil. The hunters gave the stags’ skulls to women who fed their cooking fires with wood till they burned fierce, then held the roots of the antlers in the flames so that they would snap clean from the bone. There would be work to be done on the Old Temple in the spring, and the tribe would need scores of antler picks to make holes for the new stones that were to be fetched from Cathallo.

That winter never seemed to end. Wolves were seen by the river, but Gilan assured the tribe that all would be well when the new temple was made. This winter is the last of our woes, the high priest said, the last ill fortune before the new temple changes Ratharryn’s fate. There would be life again, and love, and warmth and happiness, and all things, Gilan assured the tribe, would be good.

Camaban had gone to Cathallo to learn. He had been alone for years, scavenging a thin living beyond Ratharryn’s embankment, and in those years he had listened to the voices in his head and he had thought about what they told him. Now he wanted to test that knowledge against the world’s other wisdom, and no one was wiser than Sannas, sorceress of Cathallo, and so Camaban listened.

In the beginning, Sannas said, Slaol and Lahanna had been lovers. They had circled the world in an endless dance, the one ever close to the other, but then Slaol had glimpsed Garlanna, the goddess of the earth who was Lahanna’s daughter, and he had fallen in love with Garlanna and rejected Lahanna.

So Lahanna had lost her brightness, and thus night came to the world.

But Garlanna, Sannas insisted, stayed loyal to her mother by refusing to join Slaol’s dance and so the sun god sulked and winter came to the earth. And Slaol still sulked, and would not listen to the folk on earth, for they reminded him of Garlanna. Which is why, Sannas insisted, Lahanna should be worshipped above all other gods because she alone had the power to protect the world from Slaol’s petulance.

Camaban listened, just as he listened to Morthor, Derrewyn’s father, who was high priest at Cathallo, and Morthor told a similar tale, though in his telling it was Lahanna who sulked and who hid her face in shame because she had tried and failed to dim her lover’s brightness. She still tried to diminish Slaol, and those were fearful times when Lahanna slid herself in front of Slaol to bring night in the daytime. Morthor claimed that Lahanna was the petulant goddess, and though he was Sannas’s grandson and though the two disagreed, they did not fight. ‘The gods must be balanced,’ Morthor claimed. ‘Lahanna might try to punish us because we live on Garlanna’s earth, but she is still powerful and must be placated.’

‘Men won’t condemn Slaol,’ Sannas told Camaban, ‘for they see nothing wrong with him loving a mother and her daughter.’ She spat. ‘Men are like pigs rolling in their own dung.’

‘If you visit a strange tribe,’ Morthor said, ‘to whom do you go? Its chief! So we must worship Slaol above all the gods.’

‘Men can worship whatever they want,’ Sannas said, ‘but it is a woman’s prayer that is heard, and women pray to Lahanna.’

On one thing, though, both Sannas and Morthor agreed: that the grief of this world had come when Slaol and Lahanna parted, and that ever since the tribes of men had striven to balance their worship of the two jealous gods. It was the same belief that Hirac had held, a belief that gripped the heartland tribes and forced them to be cautious of all the gods.

Camaban heard all this, and he asked questions, but kept his own opinions silent. He had come to learn, not to argue, and Sannas had much to teach him. She was the most famous healer in the land and folk came to her from a dozen tribes. She used herbs, fungi, fire, bone, blood, pelts and charms. Barren women would walk for days to beg her help, and each morning would find a desperate collection of the sick, the crippled, the lame and the sad waiting at the shrine’s northern entrance. Camaban collected Sannas’s herbs, picked mushrooms and cut fungi from decaying trees. He dried the medicines in nets over the fire, he sliced them, infused them and learned the names that Sannas gave them. He listened as the folk described their ills and he watched what Sannas gave them, then marked their progress to health or to death. Many came complaining of pain, just pain, and as often as not they would rub their bellies and Sannas would give them slices of fungi to chew, or else made them drink a thick mixture of herbs, fungus and fresh blood. Almost as many complained of pain in their joints, a fierce pain that doubled them over and made it hard for a man to till a field or for a woman to grind a quern stone, and if the pain was truly crippling Sannas would lay the sufferer between two fires, then take a newly chipped flint knife and drag it across the painful joint. Back and forth she would cut, slicing deep so that the blood welled up, then Camaban would rub dried herbs into the wounds and place more of the dried herbs over the fresh cuts until the blood no longer seeped and Sannas would set fire to the herbs and the flames would hiss and smoke and the hut would fill with the smell of burning flesh.

One man went mad in that hard wintertime, beating his wife until she died, then hurling his youngest child onto his hut fire and Sannas decreed that the man had been possessed of an evil spirit. He was brought to her, then pinioned between two warriors as Sannas cut open his scalp, peeled back the flesh, and chipped a hole in his skull with a small stone maul and a thin flint blade. She levered out a whole circle of bone, then spat onto his brain and demanded that the evil thing come out. The man lived, though in such misery it would have been better had he died.

Camaban learned to set bones, to fill wounds with moss and spider web, and to make the potions that give men dreams. He carried those potions to Cathallo’s priests who treated him with awe because he had been chosen by Sannas. He learned to make the glutinous poison that warriors smeared on their arrow-heads when they hunted Outfolk in the wide forests north of Cathallo. The poison was made from a mixture of urine, faeces and the juice of a flowering herb that Sannas prized as a killer. He made Sannas’s food, grinding it to a paste because, only having the one tooth, she could not chew. He learned her spells, learned her chants, learned the names of a thousand gods, and when he was not learning from Sannas he listened to the traders when they returned with strange tales from their long journeys. He listened to everything, forgot nothing and kept his opinions locked inside his head. Those opinions had not changed. The voices that had spoken in his head still echoed there, still woke him at night, still filled him with wonder. He had learned how to heal and how to frighten and how to twist the world to the gods’ wishes, but he had not changed. The world’s wisdom had left his own untouched.

In the winter’s heart, when Slaol was at his weakest and Lahanna was shining brightly on Cathallo’s shrine to touch the boulders with a sheen of glistening cold light, Sannas brought two warriors to the temple. ‘It is time,’ she told Camaban.

The warriors laid Camaban on his back beside one of the temple’s taller stones. One man held Camaban’s shoulders, while the other held the crippled foot towards the full moon. ‘I will either kill you,’ Sannas said, ‘or cure you.’ She held a maul of stone and a blade that had been made from the scapula of a dead man and she laid the bone blade on the grotesquely curled ball of Camaban’s foot. ‘It will hurt,’ she said, then laughed as if Camaban’s pain would give her pleasure.

The warrior holding the foot flinched as the maul hammered on the bone. Sannas hammered again, showing a remarkable strength for such an old woman. Blood, black in the moonlight, was pouring from the foot, soaking the warrior’s hands and running down Camaban’s leg. Sannas beat the maul on the blade again, then wrenched the scapula free and gritted her teeth as she forced the curl of Camaban’s clenched foot outwards. ‘You have toes!’ she marvelled, and the two warriors shuddered and turned away as they heard the cracking of cartilage, the splintering of bone and the grating of the broken being straightened. ‘Lahanna!’ Sannas cried, and hammered the blade into Camaban’s foot again, forcing its sharpened edge into another tight part of the bulbous flesh and fused bone.