По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

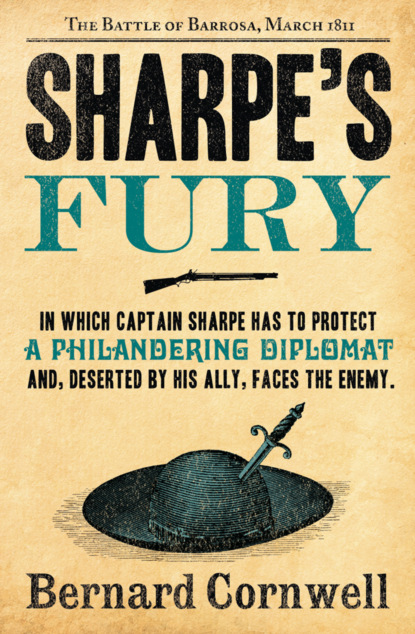

Sharpe’s Fury: The Battle of Barrosa, March 1811

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Sharpe thought for a second. ‘I doubt we can catch the others,’ he said, ‘so probably the best thing is to go downriver. Find a British ship on the coast. We’ll be in Lisbon in five days, and back with the battalion in six.’

‘Now that would be nice,’ Harper said fervently.

Sharpe smiled. ‘Joana?’ he asked. Joana was a Portuguese girl whom Harper had rescued in Coimbra and who now shared the sergeant’s quarters.

‘I’m fond of the girl,’ Harper admitted airily. ‘And she’s a good lass. She can cook, mend, works hard.’

‘Is that all she does?’ Sharpe asked.

‘She’s a good girl,’ Harper insisted.

‘You should marry her then,’ Sharpe said.

‘There’s no call for that, sir,’ Harper said, sounding alarmed.

‘I’ll ask Colonel Lawford when we’re back,’ Sharpe said. Officially only six wives were allowed with the men of each company, but the colonel could give permission to add another to the strength.

Harper looked at Sharpe for a long time, trying to work out whether he was being serious or not, but Sharpe’s face gave away nothing. ‘The colonel’s got enough to worry about, sir, so he does,’ Harper said.

‘What’s he got to worry about? We do all the work.’

‘But he’s a colonel, sir, he’s got to worry.’

‘And I worry about you, Pat. I worry that you’re a sinner. It worries me that you’ll be going to hell when you die.’

‘At least I can keep you company there, sir.’

Sharpe laughed at that. ‘That’s true, so maybe I won’t ask the colonel.’

‘You escaped, Sergeant,’ Slattery said, amused.

‘But it all depends on Moon, doesn’t it?’ Sharpe said. ‘If he wants to cross the river and try to catch the others, that’s what we’ll have to do. If he wants to go downriver we go downriver, but one way or another we should get you back to Joana in a week.’ He saw a horseman appear on the northern hill from which he had first glimpsed the house and town, and he took out his telescope, but by the time he had trained it the man had gone. Probably a hunter, he told himself. ‘So be ready to move, Pat. And you’ll have to fetch the brigadier. He’s got crutches now, but if the bloody Frogs show we’ll need to get him down to the river fast so you’ll have to carry him.’

‘There’s a wheelbarrow in the stable yard, sir,’ Hagman said. ‘A dung barrow.’

‘I’ll put it on the terrace,’ Sharpe said.

He found the barrow behind a heap of horse manure and wheeled it to the terrace and parked it beside the door. He had done all he could now. He had a boat, it was guarded, the men were ready, and all now depended on Moon giving the orders.

He sat outside the brigadier’s door and took off his hat so the winter sun could warm his face. He closed his eyes in tiredness and within seconds he was asleep, his head tipped back onto the house wall beside the door. He was dreaming, and he was aware it was a good dream, and then someone hit him hard across the head, and that was no dream. He scrambled sideways, reaching for his rifle, and was hit again. ‘Impudent puppy!’ a voice shrieked, and then she hit him again. She was an old woman, older than Sharpe could imagine, with a brown face like sun-dried mud, all cracks and wrinkles and malevolence and bitterness. She was dressed in black with a black widow’s veil pinned to her white hair. Sharpe stood up, rubbing his head where she had hit him with one of the brigadier’s borrowed crutches. ‘You dare attack one of my servants?’ she shrieked. ‘You insolent cur!’

‘Ma’am,’ Sharpe said for want of anything else to say.

‘You break into my boathouse!’ she said in a grating voice. ‘You assault my servant! If the world were respectable you would be whipped. My husband would have whipped you.’

‘Your husband, ma’am?’

‘He was the Marquis de Cardenas and he had the misfortune to be ambassador to the Court of St James for eleven sad years. We lived in London. A horrid city. A vile city. Why did you attack my gardener?’

‘Because he attacked me, ma’am.’

‘He says not.’

‘If the world were a respectable place, ma’am, then an officer’s word would be preferred to a servant’s.’

‘You impudent puppy! I feed you, I shelter you, and you reward me with barbarism and lies. Now you wish to steal my son’s boat?’

‘Borrow it, ma’am.’

‘You can’t,’ she snapped. ‘It belongs to my son.’

‘He’s here, ma’am?’

‘He is not, nor should you be. What you will do is march away from here once the doctor has seen your brigadier. You may take the crutches, nothing else.’

‘Yes, ma’am.’

‘Yes, ma’am,’ she mimicked him, ‘so humble.’ A bell sounded deep in the house and she turned away. ‘El médico,’ she muttered.

Private Geoghegan appeared then, running up from the kitchen garden. ‘Sir,’ he panted, ‘there are men there.’

‘Men where?’

‘Boathouse, sir. A dozen of them. All got guns. I think they came from the town, sir. Sergeant Noolan told me to tell you and ask what’s to be done, sir?’

‘They’re guarding the boat?’

‘That’s it, sir, that’s just what they’re doing. They’re stopping us getting to the boathouse, sir. Just that, sir. Jesus, what was that?’

The brigadier had given a sudden yelp, presumably as the doctor explored the makeshift splint. ‘Tell Sergeant Noolan,’ Sharpe said, ‘that he’s to do nothing. Just watch the men and make sure they don’t take the boat away.’

‘Not to take the boat away, sir. And if they try?’

‘You bloody stop them. You fix swords,’ he paused, then corrected himself because only the rifles talked about fixing swords, ‘you fix bayonets and you walk slowly towards them and you point the bayonets at their crotches and they’ll run.’

‘Aye, sir, yes, sir.’ Geoghegan grinned. ‘But really, sir, we’re to do nothing else?’

‘It’s usually best.’

‘Oh, the poor man!’ Geoghegan glanced at the door. ‘And if he’d left it alone it would have been fine. Thank you, sir.’

Sharpe swore silently when Geoghegan was gone. It had all seemed so simple when he had discovered the boat, but he should have known nothing was ever that easy. And if the marquesa had summoned men from the town then there was a chance of bloodshed, and though Sharpe had no doubt that his soldiers would brush the townsmen away he also feared that he would take two or three more casualties. ‘Bloody hell,’ he said aloud, and, because there was nothing else to do, went back to the kitchen and rousted Harris from the table. ‘You’re to stand outside the brigadier’s room,’ he told him, ‘and let me know when the doctor’s finished.’

He went up to the tower where Harper still stood guard. ‘Nothing moving, sir,’ Harper said, ‘except I thought I saw a horseman up there a half-hour ago,’ he pointed to the northern heights, ‘but he’s gone.’

‘I thought I saw the same thing.’

‘He’s not there now, sir.’