По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

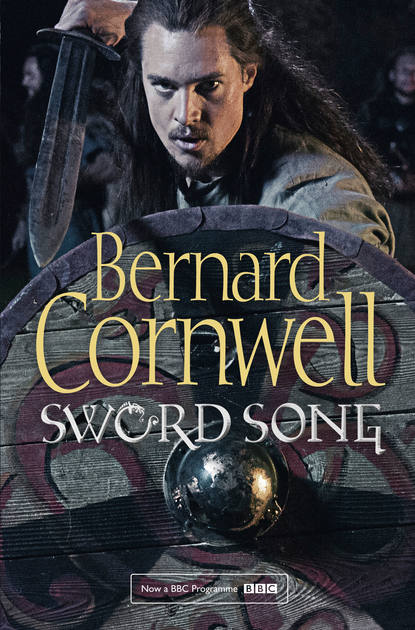

Sword Song

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He liked that. He laughed again and put a heavy hand on my shoulder to lead me towards the cross. ‘You’re a Saxon, they tell me?’

‘I am.’

‘But no Christian?’

‘I worship the true gods,’ I said.

‘May they love and reward you for that,’ he said, and he squeezed my shoulder and, even through the mail and leather, I could feel his strength. He turned then. ‘Erik! Are you shy?’

His brother stepped out of the crowd. He had the same black bushy hair, though Erik’s was tied severely back with a length of cord. His beard was trimmed. He was young, maybe only twenty or twenty-one, and he had a broad face with bright eyes that were at once full of curiosity and welcome. I had been surprised to discover I liked Sigefrid, but it was no surprise to like Erik. His smile was instant, his face open and guileless. He was, like Gisela’s brother, a man you liked from the moment you met him.

‘I am Erik,’ he greeted me.

‘He is my adviser,’ Sigefrid said, ‘my conscience and my brother.’

‘Conscience?’

‘Erik would not kill a man for telling a lie, would you, brother?’

‘No,’ Erik said.

‘So he is a fool, but a fool I love.’ Sigefrid laughed. ‘But don’t think the fool is a weakling, Lord Uhtred. He fights like a demon from Niflheim.’ He slapped his brother on the shoulder, then took my elbow and led me on towards the incongruous cross. ‘I have prisoners,’ he explained as we neared the cross, and I saw that five men were kneeling with their hands tied behind their backs. They had been stripped of cloaks, weapons and tunics so that they wore only their trews. They shivered in the cold air.

The cross had been newly made from two beams of wood that had been crudely nailed together and then sunk into a hastily dug hole. The cross leaned slightly. At its foot were some heavy nails and a big hammer. ‘You see death by the cross on their statues and carvings,’ Sigefrid explained to me, ‘and you see it on the amulets they wear, but I’ve never seen the real thing. Have you?’

‘No,’ I admitted.

‘And I can’t understand why it would kill a man,’ he said with genuine puzzlement in his voice. ‘It’s only three nails! I’ve suffered much worse than that in battle.’

‘Me too,’ I said.

‘So I thought I’d find out!’ he finished cheerfully, then jerked his big beard towards the prisoner nearest to the foot of the cross. ‘The two bastards at the end there are Christian priests. We’ll nail one of them up and see if he dies. I have ten pieces of silver that say it won’t kill him.’

I could see almost nothing of the two priests except that one had a big belly. His head was bowed, not in prayer, but because he had been beaten hard. His naked back and chest were bruised and bloody, and there was more blood in the tangle of his brown curly hair. ‘Who are they?’ I asked Sigefrid.

‘Who are you?’ he snarled at the prisoners and, when none answered, he gave the nearest man a brutal kick in the ribs. ‘Who are you?’ he asked again.

The man lifted his head. He was elderly, at least forty years old, and had a deep lined face on which was etched the resignation of those who knew they were about to die. ‘I am Earl Sihtric,’ he said, ‘counsellor to King Æthelstan.’

‘Guthrum!’ Sigefrid screamed, and it was a scream. A scream of pure rage that erupted from nowhere. One moment he had been affable, but suddenly he was a demon. Spittle flew from his mouth as he shrieked the name a second time. ‘Guthrum! His name is Guthrum, you bastard!’ He kicked Sihtric in the chest, and I reckoned that kick was hard enough to break a rib. ‘What is his name?’ Sigefrid demanded.

‘Guthrum,’ Sihtric said.

‘Guthrum!’ Sigefrid shouted, and kicked the old man again. Guthrum, when he made peace with Alfred, had become a Christian and taken the Christian name Æthelstan as his own. I still thought of him as Guthrum, as did Sigefrid, who now appeared to be trying to stamp Sihtric to death. The old man attempted to evade the blows, but Sigefrid had driven him to the ground from where he could not escape. Erik seemed unmoved by his brother’s savage anger, yet after a while he stepped forward and took Sigefrid’s arm and the bigger man allowed himself to be pulled away. ‘Bastard!’ Sigefrid spat back at the moaning man. ‘Calling Guthrum by a Christian name!’ he explained to me. Sigefrid was still shaking from his sudden anger. His eyes had narrowed and his face was contorted, but he seemed to control himself as he draped a heavy arm around my shoulder. ‘Guthrum sent them,’ he said, ‘to tell me to leave Lundene. But it’s none of Guthrum’s business! Lundene doesn’t belong to East Anglia! It belongs to Mercia! To King Uhtred of Mercia!’ That was the first time anyone had used that title so formally, and I liked the sound of it. King Uhtred. Sigefrid turned back to Sihtric who now had blood at his lips. ‘What was Guthrum’s message?’

‘That the city belongs to Mercia, and you must leave,’ Sihtric managed to say.

‘Then Mercia can throw me out,’ Sigefrid sneered.

‘Unless King Uhtred allows us to stay?’ Erik suggested with a smile.

I said nothing. The title sounded good, but strange, as if it defied the strands coming from the three spinners.

‘Alfred will not permit you to stay.’ One of the other prisoners dared to speak.

‘Who gives a turd about Alfred?’ Sigefrid snarled. ‘Let the bastard send his army to die here.’

‘That is your reply, lord?’ the prisoner asked humbly.

‘My reply will be your severed heads,’ Sigefrid said.

I glanced at Erik then. He was the younger brother, but clearly the one who did the thinking. He shrugged. ‘If we negotiate,’ he explained, ‘then we give time for our enemies to gather their forces. Better to be defiant.’

‘You’ll pick war with both Guthrum and Alfred?’ I asked.

‘Guthrum won’t fight,’ Erik said, sounding very certain. ‘He threatens, but he won’t fight. He’s getting old, Lord Uhtred, and he would prefer to enjoy what life is left to him. And if we send him severed heads? I think he will understand the message that his own head is in danger if he disturbs us.’

‘What of Alfred?’ I asked.

‘He’s cautious,’ Erik said, ‘isn’t he?’

‘Yes.’

‘He’ll offer us money to leave the city?’

‘Probably.’

‘And maybe we’ll take it,’ Sigefrid said, ‘and stay anyway.’

‘Alfred won’t attack us till the summer,’ Erik said, ignoring his brother, ‘and by then, Lord Uhtred, we hope you will have led Earl Ragnar south into East Anglia. Alfred can’t ignore that threat. He will march against our combined armies, not against the garrison in Lundene, and our job is to kill Alfred and put his nephew on the throne.’

‘Æthelwold?’ I asked dubiously. ‘He’s a drunk.’

‘Drunk or not,’ Erik said, ‘a Saxon king will make our conquest of Wessex more palatable.’

‘Until you need him no longer,’ I said.

‘Until we need him no longer,’ Erik agreed.

The big-bellied priest at the end of the line of kneeling prisoners had been listening. He stared at me, then at Sigefrid, who saw his gaze. ‘What are you looking at, turd?’ Sigefrid demanded. The priest did not answer, but just looked at me again, then dropped his head. ‘We’ll start with him,’ Sigefrid said, ‘we’ll nail the fat bastard to a cross and see if he dies.’

‘Why not let him fight?’ I suggested.

Sigefrid stared at me, unsure he had heard me correctly. ‘Let him fight?’ he asked.

‘The other priest is skinny,’ I said, ‘so much easier to nail to the cross. That fat one should be given a sword and made to fight.’

Sigefrid sneered. ‘You think a priest can fight?’