По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

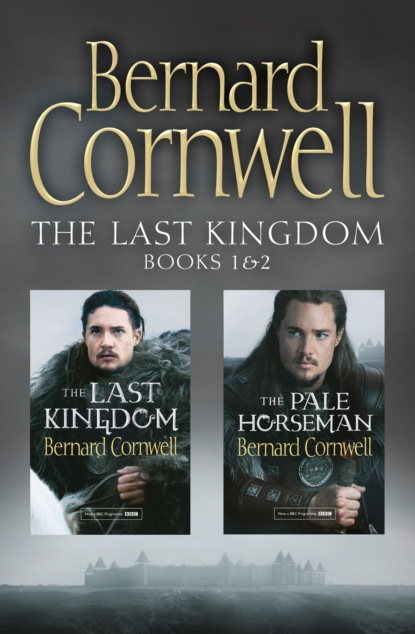

The Last Kingdom Series Books 1 and 2: The Last Kingdom, The Pale Horseman

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘They will worship Odin,’ I said, again meaning it.

‘Christianity is a soft religion,’ Ravn said savagely, ‘a woman’s creed. It doesn’t ennoble men, it makes them into worms. I hear birds.’

‘Two ravens,’ I said, ‘flying north.’

‘A real message!’ he said delightedly, ‘Huginn and Muminn are going to Odin.’

Huginn and Muminn were the twin ravens that perched on the god’s shoulders where they whispered into his ear. They did for Odin what I did for Ravn, they watched and told him what they saw. He sent them to fly all over the world and to bring back news, and the news they carried back that day was that the smoke from the Mercian encampment was less thick. Fewer fires were lit at night. Men were leaving that army.

‘Harvest time,’ Ravn said in disgust.

‘Does that matter?’

‘They call their army the fyrd,’ he explained, forgetting for a moment that I was English, ‘and every able man is supposed to serve in the fyrd, but when the harvest ripens they fear hunger in the winter so they go home to cut their rye and barley.’

‘Which we then take?’

He laughed. ‘You’re learning, Uhtred.’

Yet the Mercians and West Saxons still hoped they could starve us and, though they were losing men every day, they did not give up until Ivar loaded a cart with food. He piled cheeses, smoked fish, newly baked bread, salted pork and a vat of ale onto the cart and, at dawn, a dozen men dragged it towards the English camp. They stopped just out of bowshot and shouted to the enemy sentries that the food was a gift from Ivar the Boneless to King Burghred.

Next day a Mercian horseman rode towards the town carrying a leafy branch as a sign of truce. The English wanted to talk. ‘Which means,’ Ravn told me, ‘that we have won.’

‘It does?’

‘When an enemy wants to talk,’ he said, ‘it means he does not want to fight. So we have won.’

And he was right.

Three (#ulink_e7f34d18-76c4-534a-9f3d-9aede0038d90)

Next day we made a pavilion in the valley between the town and the English encampment, stretching two ships’ sails between timber poles, the whole thing supported by seal-hide ropes lashed to pegs, and there the English placed three high-backed chairs for King Burghred, King Æthelred and for Prince Alfred, and draped the chairs with rich red cloths. Ivar and Ubba sat on milking stools.

Both sides brought thirty or forty men to witness the discussions, which began with an agreement that all weapons were to be piled twenty paces behind the two delegations. I helped carry swords, axes, shields and spears, then went back to listen.

Beocca was there and he spotted me. He smiled. I smiled back. He was standing just behind the young man I took to be Alfred, for though I had heard him in the night I had not seen him clearly. He alone among the three English leaders was not crowned with a circlet of gold, though he did have a large, jewelled cloak brooch which Ivar eyed rapaciously. I saw, as Alfred took his seat, that the prince was thin, long-legged, restless, pale and tall. His face was long, his nose long, his beard short, his cheeks hollow and his mouth pursed. His hair was a nondescript brown, his eyes worried, his brow creased, his hands fidgety and his face frowning. He was only nineteen, I later learned, but he looked ten years older. His brother, King Æthelred, was much older, over thirty, and he was also long-faced, but burlier and even more anxious-looking, while Burghred, King of Mercia, was a stubby man, heavy-bearded, with a bulging belly and a balding pate.

Alfred said something to Beocca who produced a sheet of parchment and a quill which he gave to the prince. Beocca then held a small vial of ink so that Alfred could dip the quill and write.

‘What is he doing?’ Ivar asked.

‘He is making notes of our talks,’ the English interpreter answered.

‘Notes?’

‘So there is a record, of course.’

‘He has lost his memory?’ Ivar asked, while Ubba produced a very small knife and began to clean his fingernails. Ragnar pretended to write on his hand, which amused the Danes.

‘You are Ivar and Ubba?’ Alfred asked through his interpreter.

‘They are,’ our translator answered. Alfred’s pen scratched, while his brother and brother-in-law, both kings, seemed content to allow the young prince to question the Danes.

‘You are sons of Lothbrok?’ Alfred continued.

‘Indeed,’ the interpreter answered.

‘And you have a brother? Halfdan?’

‘Tell the bastard to shove his writing up his arse,’ Ivar snarled, ‘and to shove the quill up after it, and then the ink until he shits black feathers.’

‘My lord says we are not here to discuss family,’ the interpreter said suavely, ‘but to decide your fate.’

‘And to decide yours,’ Burghred spoke for the first time.

‘Our fate?’ Ivar retorted, making the Mercian king quail from the force of his skull-gaze, ‘our fate is to water the fields of Mercia with your blood, dung the soil with your flesh, pave it with your bones, and rid it of your filthy stink.’

The discussion carried on like that for a long time, both sides threatening, neither yielding, but it had been the English who called for the meeting and the English who wanted to make peace and so the terms were slowly hammered out. It took two days, and most of us who were listening became bored and lay on the grass in the sunlight. Both sides ate in the field, and it was during one such meal that Beocca cautiously came across to the Danish side and greeted me warily. ‘You’re getting tall, Uhtred,’ he said.

‘It is good to see you, father,’ I answered dutifully. Ragnar was watching, but without any sign of worry on his face.

‘You’re still a prisoner, then?’ Beocca asked.

‘I am,’ I lied.

He looked at my two silver arm rings which, being too big for me, rattled at my wrist. ‘A privileged prisoner,’ he said wryly.

‘They know I am an Ealdorman,’ I said.

‘Which you are, God knows, though your uncle denies it.’

‘I have heard nothing of him,’ I said truthfully.

Beocca shrugged. ‘He holds Bebbanburg. He married your father’s wife and now she is pregnant.’

‘Gytha!’ I was surprised. ‘Pregnant?’

‘They want a son,’ Beocca said, ‘and if they have one …’ he did not finish the thought, but nor did he need to. I was the Ealdorman, and Ælfric had usurped my place, yet I was still his heir and would be until he had a son. ‘The child must be born any day now,’ Beocca said, ‘but you need not worry.’ He smiled and leaned towards me so he could speak in a conspiratorial whisper. ‘I brought the parchments.’

I looked at him with utter incomprehension. ‘You brought the parchments?’

‘Your father’s will! The land-charters!’ He was shocked that I did not immediately understand what he had done. ‘I have the proof that you are the Ealdorman!’

‘I am the Ealdorman,’ I said, as if proof did not matter. ‘And always will be.’

‘Not if Ælfric has his way,’ Beocca said, ‘and if he has a son then he will want the boy to inherit.’

‘Gytha’s children always die,’ I said.