По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

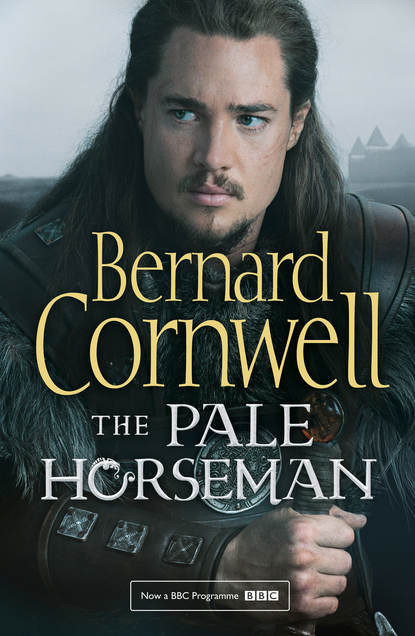

The Pale Horseman

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Yet the world did not end to the north. I knew that, though I was not certain what did lie northwards. Dyfed was there, somewhere, and Ireland, and there were other places with barbarous names and savage people who lived like hungry dogs on the wild edges of the land, but there was also a waste of sea, a wilderness of empty waves and so, once the sail was hoisted and the wind was thrusting the Fyrdraca northwards, I leaned on the oar to take her somewhat to the east for fear we would otherwise be lost in the ocean’s vastness.

‘You know where you’re going?’ Leofric asked me.

‘No.’

‘Do you care?’

I grinned at him for answer. The wind, which had been southerly, came more from the west, and the tide took us eastwards, so that by the afternoon I could see land, and I thought it must be the land of the Britons on the north side of the Sæfern, but as we came closer I saw it was an island. I later discovered it was the place the Northmen call Lundi, because that is their word for the puffin, and the island’s high cliffs were thick with the birds, which shrieked at us when we came into a cove on the western side of the island. It was an uncomfortable place to anchor for the night because the big seas rolled in and so we dropped the sail, took out the oars, and rowed around the cliffs until we found shelter on the eastern side.

I went ashore with Iseult and we dug some puffin burrows to find eggs, though all were hatched so we contented ourselves with killing a pair of goats for the evening meal. There was no one living on the island, though there had been because there were the remains of a small church and a field of graves. The Danes had burned everything, pulled down the church and dug up the graves in search of gold. We climbed to a high place and I searched the evening sea for ships, but saw none, though I wondered if I could see land to the south. It was hard to be sure for the southern horizon was thick with dark cloud, but a darker strip within the cloud could have been hills and I assumed I was looking at Cornwalum or the western part of Wessex. Iseult sang to herself.

I watched her. She was gutting one of the dead goats, doing it clumsily for she was not accustomed to such work. She was thin, so thin that she looked like the ælfcynn, the elf-kind, but she was happy. In time I would learn just how much she had hated Peredur. He had valued her and made her a queen, but he had also kept her a prisoner in his hall so that he alone could profit from her powers. Folk would pay Peredur to hear Iseult’s prophecies and one of the reasons Callyn had fought his neighbour was to take Iseult for himself. Shadow queens were valued among the Britons for they were part of the old mysteries, the powers that had brooded over the land before the monks arrived, and Iseult was one of the last shadow queens. She had been born in the sun’s darkness, but now she was free and I was to find she had a soul as wild as a falcon. Mildrith, poor Mildrith, wanted order and routine. She wanted the hall swept, the clothes clean, the cows milked, the sun to rise, the sun to set and for nothing to change, but Iseult was different. She was strange, shadow-born, and full of mystery. Nothing she said to me those first days made any sense, for we had no language in common, but on the island, as the sun set and I took the knife to finish cutting the entrails from the goat, she plucked twigs and wove a small cage. She showed me the cage, broke it and then, with her long white fingers, mimed a bird flying free. She pointed to herself, tossed the twig scraps away and laughed.

Next morning, still ashore, I saw boats. There were two of them and they were sailing to the west of the island, going northwards. They were small craft, probably traders from Cornwalum, and they were running before the south-west wind towards the hidden shore where I assumed Svein had taken the White Horse.

We followed the two small ships. By the time we had waded out to Fyrdraca, raised her anchor and rowed her from the lee of the island both boats were almost out of sight, but once our sail was hoisted we began to overhaul them. They must have been terrified to see a dragon ship shoot out from behind the island, but I lowered the sail a little to slow us down and so followed them for much of the day until, at last, a blue-grey line showed at the sea’s edge. Land. We hoisted the sail fully and seethed past the two small, tubby boats and so, for the first time, I came to the shore of Wales. The Britons had another name for it, but we simply called it Wales which means ‘foreigners’, and much later I worked out that we must have made that landfall in Dyfed, which is the name of the churchman who converted the Britons of Wales to Christianity and had the westernmost kingdom of the Welsh named for him.

We found a deep inlet for shelter. Rocks guarded the entrance, but once inside we were safe from wind and sea. We turned the ship so that her bows faced the open sea, and the cove was so narrow that our stern scraped stone as we slewed Fyrdraca about, and then we slept on board, men and their women sprawled under the rowers’ benches. There were a dozen women aboard, all captured from Peredur’s tribe, and one of them managed to escape that night, presumably sliding over the side and swimming to shore. It was not Iseult. She and I slept in the small black space beneath the steering platform, a hole screened by a cloak, and Leofric woke me there in the dawn, worried that the missing woman would raise the country against us. I shrugged. ‘We won’t be here long.’

But we stayed in the cove all day. I wanted to ambush ships coming around the coast and we saw two, but they travelled together and I could not attack more than one ship at a time. Both ships were under sail, riding the south-west wind, and both were Danish, or perhaps Norse, and both were laden with warriors. They must have come from Ireland, or perhaps from the east coast of Northumbria, and doubtless they travelled to join Svein, lured by the prospect of capturing good West Saxon land. ‘Burgweard should have the whole fleet up here,’ I said. ‘He could tear through these bastards.’

Two horsemen came to look at us in the afternoon. One had a glinting chain about his neck, suggesting he was of high rank, but neither man came down to the shingle beach. They watched from the head of the small valley that fell to the cove and after a while they went away. The sun was low now, but it was summer so the days were long. ‘If they bring men,’ Leofric said as the two horsemen rode away, but he did not finish the thought.

I looked up at the high bluffs on either side of the cove. Men could rain rocks down from those heights and the Fyrdraca would be crushed like an egg. ‘We could put sentries up there,’ I suggested, but just then Eadric, who led the men who occupied the forward steorbord benches, shouted that there was a ship in sight. I ran forward and there she was.

The perfect prey.

She was a large ship, not so big as Fyrdraca, but large all the same, and she was riding low in the water for she was so heavily laden. Indeed, she carried so many people that her crew had not dared raise the sail for, though the wind was not heavy, it would have bent her leeward side dangerously close to the water. So she was being rowed and now she was close inshore, evidently looking for a place where she could spend the night and her crew had plainly been tempted by our cove and only now realised that we already filled it. I could see a man in her bows pointing further up the coast and meanwhile my men were arming themselves, and I shouted at Haesten to take the steering oar. He knew what to do and I was confident he would do it well, even though it might mean the death of fellow Danes. We cut the lines that had tethered us to the shore as Leofric brought me my mail coat, helmet and shield. I dressed for battle as the oars were shipped, then pulled on my helmet so that suddenly the edges of my vision were darkened by its face-plate.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: