По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

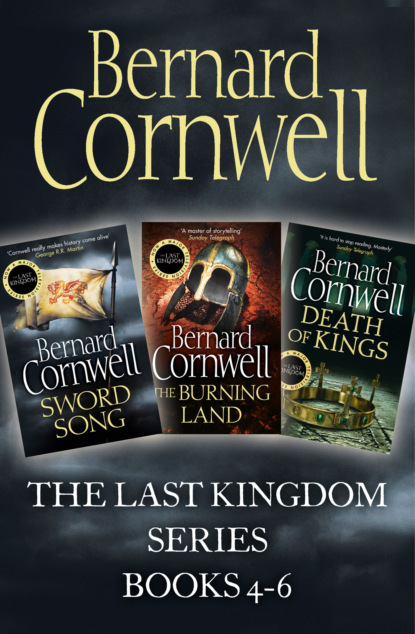

The Last Kingdom Series Books 4-6: Sword Song, The Burning Land, Death of Kings

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

CONTENTS

Title Page (#u6b5982df-aff0-5cbe-9b67-b1e09a381bb0)

Copyright (#udcbab180-8230-5d47-a82b-901d652ebdd9)

Dedication (#uacb781b6-3d2c-5ea1-874d-41453c21fb6f)

Place Names (#u13d202ba-a5b4-5b28-87e9-02047b2ded77)

Map (#u3cb795e3-2113-5552-a92f-7577723353b4)

Prologue (#u70fe5adb-e272-5bba-9120-4e056e0b8c30)

Part One: THE BRIDE (#u7229c28e-83c2-5714-bc10-30b35093cdc4)

Chapter One (#ubfe60ac6-7bb4-5815-bc1d-3854b594e329)

Chapter Two (#u684f510a-9069-546e-89c4-ad6cccd0f37a)

Chapter Three (#u3536d28f-3130-5e36-9e71-992840c59f80)

Part Two: THE CITY (#u38c8115f-d09e-584c-b238-3bf3cb2ecbe9)

Chapter Four (#ucc1cd059-9281-55f8-84a6-0783fd2303e2)

Chapter Five (#uc49cbdb6-3017-5a0d-b932-d78ac916e089)

Chapter Six (#u41510571-6357-5cfe-91ad-8371e88d9f14)

Chapter Seven (#u5e879f98-eef3-55fe-a04f-b5c762d152e7)

Chapter Eight (#ube798bbe-9caa-5147-b453-85614e67747a)

Part Three: THE SCOURING (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Historical Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Place Names (#ulink_55ec5da2-37cb-5900-9b86-9c5489007b41)

The spelling of Place Names in Anglo Saxon England was an uncertain business, with no consistency and no agreement even about the name itself. Thus London was variously rendered as Lundonia, Lundenberg, Lundenne, Lundene, Lundenwic, Lundenceaster and Lundres. Doubtless some readers will prefer other versions of the names listed below, but I have usually employed whichever spelling is cited in either the Oxford Dictionary of English Place Names or the Cambridge Dictionary of English Place Names for the years nearest or contained within Alfred’s reign, AD 871–899, but even that solution is not foolproof. Hayling Island, in 956, was written as both Heilincigae and Hæglingaiggæ. Nor have I been consistent myself; I should spell England as Englaland, and have preferred the modern form Northumbria to Norðhymbralond to avoid the suggestion that the boundaries of the ancient kingdom coincide with those of the modern county. So this list, like the spellings themselves, is capricious.

PROLOGUE (#ulink_dde75579-47b3-51c1-b26b-75aedb46c0c5)

Darkness. Winter. A night of frost and no moon.

We floated on the River Temes, and beyond the boat’s high bow I could see the stars reflected on the shimmering water. The river was in spate as melted snow fed it from countless hills. The winterbournes were flowing from the chalk uplands of Wessex. In summer those streams would be dry, but now they foamed down the long green hills and filled the river and flowed to the distant sea.

Our boat, which had no name, lay close to the Wessex bank. North across the river lay Mercia. Our bows pointed upstream. We were hidden beneath the leafless, bending branches of three willow trees, held there against the current by a leather mooring rope tied to one of those branches.

There were thirty-eight of us in that nameless boat, which was a trading ship that worked the upper reaches of the Temes. The ship’s master was called Ralla and he stood beside me with one hand on the steering-oar. I could hardly see him in the darkness, but knew he wore a leather jerkin and had a sword at his side. The rest of us were in leather and mail, had helmets and carried shields, axes, swords or spears. Tonight we would kill.

Sihtric, my servant, squatted beside me and stroked a whetstone along the blade of his short-sword. ‘She says she loves me,’ he told me.

‘Of course she says that,’ I said.

He paused, and when he spoke again his voice had brightened, as though he had been encouraged by my words. ‘And I must be nineteen by now, lord! Maybe even twenty?’

‘Eighteen?’ I suggested.

‘I could have been married four years ago, lord!’

We spoke almost in whispers. The night was full of noises. The water rippled, the bare branches clattered in the wind, a night creature splashed into the river, a vixen howled like a dying soul, and somewhere an owl hooted. The boat creaked. Sihtric’s stone hissed and scraped on the steel. A shield thumped against a rower’s bench. I dared not speak louder, despite the night’s noises, because the enemy ship was upstream of us and the men who had gone ashore from that ship would have left sentries on board. Those sentries might have seen us as we slipped downstream on the Mercian bank, but by now they would surely have thought we were long gone towards Lundene.

‘But why marry a whore?’ I asked Sihtric.

‘She’s …’ Sihtric began.

‘She’s old,’ I snarled, ‘maybe thirty. And she’s addled. Ealhswith only has to see a man and her thighs fly apart! If you lined up every man who’d tupped that whore you’d have an army big enough to conquer all Britain.’ Beside me Ralla sniggered. ‘You’d be in that army, Ralla?’ I asked.

‘Twenty times over, lord,’ the shipmaster said.

‘She loves me,’ Sihtric spoke sullenly.

‘She loves your silver,’ I said, ‘and besides, why put a new sword in an old scabbard?’

It is strange what men talk about before battle. Anything except what faces them. I have stood in a shield wall, staring at an enemy bright with blades and dark with menace, and heard two of my men argue furiously about which tavern brewed the best ale. Fear hovers in the air like a cloud and we talk of nothing to pretend that the cloud is not there.

‘Look for something ripe and young,’ I advised Sihtric. ‘That potter’s daughter is ready to wed. She must be thirteen.’

‘She’s stupid,’ Sihtric objected.

‘And what are you, then?’ I demanded. ‘I give you silver and you pour it into the nearest open hole! Last time I saw her she was wearing an arm ring I gave you.’

He sniffed, said nothing. His father had been Kjartan the Cruel, a Dane who had whelped Sihtric on one of his Saxon slaves. Yet Sihtric was a good boy, though in truth he was no longer a boy. He was a man who had stood in the shield wall. A man who had killed. A man who would kill again tonight. ‘I’ll find you a wife,’ I promised him.

It was then we heard the screaming. It was faint because it came from very far off, a mere scratching noise in the darkness that told of pain and death to our south. There were screams and shouting. Women were screaming and doubtless men were dying.

‘God damn them,’ Ralla said bitterly.

‘That’s our job,’ I said curtly.

‘We should …’ Ralla started, then thought better of speaking. I knew what he was going to say, that we should have gone to the village and protected it, but he knew what I would have answered.