По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

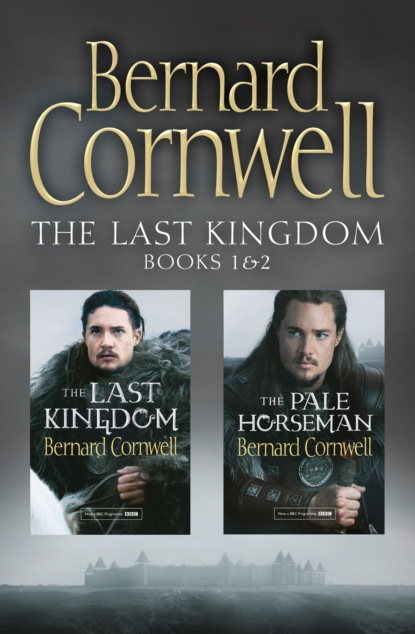

The Last Kingdom Series Books 1 and 2: The Last Kingdom, The Pale Horseman

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Will any of these monks know you?’ Ragnar asked me.

‘Probably.’

‘Does that worry you?’

It did, but I said it did not, and I touched Thor’s hammer and somewhere in my thoughts there was a tendril of worry that God, the Christian god, was watching me. Beocca always said that everything we did was watched and recorded, and I had to remind myself that the Christian god was failing and that Odin, Thor and the Danish gods were winning the war in heaven. Edmund’s death had proved that and so I consoled myself that I was safe.

The monastery lay on the south of the island from where I could see Bebbanburg on its crag of rock. The monks lived in a scatter of small timber buildings, thatched with rye and moss, and built about a small stone church. The abbot, a man called Egfrith, came to meet us carrying a wooden cross. He spoke Danish, which was unusual, and he showed no fear. ‘You are most welcome to our small island,’ he greeted us enthusiastically, ‘and you should know that I have one of your countrymen in our sick chamber.’

Ragnar rested his hands on the fleece-covered pommel of his saddle. ‘What is that to me?’ he asked.

‘It is an earnest of our peaceful intentions, lord,’ Egfrith said. He was elderly, grey-haired, thin and missing most of his teeth so that his words came out sibilant and distorted. ‘We are a humble house,’ he went on, ‘we tend the sick, we help the poor and we serve God.’ He looked along the line of Danes, grim helmeted men with their shields hanging by their left knees, swords and axes and spears bristling. The sky was low that day, heavy and sullen, and a small rain was darkening the grass. Two monks came from the church carrying a wooden box that they placed behind Egfrith, then backed away. ‘That is all the treasure we have,’ Egfrith said, ‘and you are welcome to it.’

Ragnar jerked his head at me and I dismounted, walked past the abbot and opened the box to find it was half full of silver pennies, most of them clipped, and all of them dull because they were of bad quality. I shrugged at Ragnar as if to suggest they were poor reward.

‘You are Uhtred!’ Egfrith said. He had been staring at me.

‘So?’ I answered belligerently.

‘I heard you were dead, lord,’ he said, ‘and I praise God you are not.’

‘You heard I was dead?’

‘That a Dane killed you.’

We had been talking in English and Ragnar wanted to know what had been said, so I translated. ‘Was the Dane called Weland?’ Ragnar asked Egfrith.

‘He is called that,’ Egfrith said.

‘Is?’

‘Weland is the man lying here recovering from his wounds, lord,’ Egfrith looked at me again as though he could not believe I was alive.

‘His wounds?’ Ragnar wanted to know.

‘He was attacked, lord, by a man from the fortress. From Bebbanburg.’

Ragnar, of course, wanted to hear the whole tale. It seemed Weland had made his way back to Bebbanburg where he claimed to have killed me, and so received his reward in silver coins, and he was escorted from the fortress by a half dozen men who included Ealdwulf, the blacksmith who had told me stories in his forge, and Ealdwulf had attacked Weland, hacking an axe down into his shoulder before the other men dragged him off. Weland had been brought here, while Ealdwulf, if he still lived, was back in Bebbanburg.

If Abbot Egfrith thought Weland was his safeguard, he had miscalculated. Ragnar scowled at him. ‘You gave Weland shelter even though you thought he had killed Uhtred?’ he demanded.

‘This is a house of God,’ Egfrith said, ‘so we give every man shelter.’

‘Including murderers?’ Ragnar asked, and he reached behind his head and untied the leather lace which bound his hair. ‘So tell me, monk, how many of your men went south to help their comrades murder Danes?’

Egfrith hesitated, which was answer enough, and then Ragnar drew his sword and the abbot found his voice. ‘Some did, lord,’ he admitted, ‘I could not stop them.’

‘You could not stop them?’ Ragnar asked, shaking his head so that his wet unbound hair fell around his face. ‘Yet you rule here?’

‘I am the abbot, yes.’

‘Then you could stop them.’ Ragnar was looking angry now and I suspected he was remembering the bodies we had disinterred near Gyruum, the little Danish girls with blood still on their thighs. ‘Kill them,’ he told his men.

I took no part in that killing. I stood by the shore and listened to the birds cry and I watched Bebbanburg and heard the blades doing their work, and Brida came to stand beside me and she took my hand and stared south across the white-flecked grey to the great fortress on its crag. ‘Is that your house?’ she asked.

‘That is my house.’

‘He called you lord.’

‘I am a lord.’

She leaned against me. ‘You think the Christian god is watching us.’

‘No,’ I said, wondering how she knew that I had been thinking about that very question.

‘He was never our god,’ she said fiercely. ‘We worshipped Woden and Thor and Eostre and all the other gods and goddesses, and then the Christians came and we forgot our gods, and now the Danes have come to lead us back to them.’ She stopped abruptly.

‘Did Ravn tell you that?’

‘He told me some,’ she said, ‘but the rest I worked out. There’s war between the gods, Uhtred, war between the Christian god and our gods, and when there is war in Asgard the gods make us fight for them on earth.’

‘And we’re winning?’ I asked.

Her answer was to point to the dead monks, scattered on the wet grass, their robes bloodied, and now that their killing was done Ragnar dragged Weland out of his sickbed. The man was plainly dying, for he was shivering and his wound stank, but he was conscious of what was happening to him. His reward for killing me had been a heavy bag of good silver coins that weighed as much as a new-born babe, and that we found beneath his bed and we added it to the monastery’s small hoard to be divided among our men.

Weland himself lay on the bloodied grass, looking from me to Ragnar. ‘You want to kill him?’ Ragnar asked me.

‘Yes,’ I said, for no other response was expected. Then I remembered the beginning of my tale, the day when I had seen Ragnar oar-dancing just off this coast and how, next morning, he had brought my brother’s head to Bebbanburg. ‘I want to cut off his head,’ I said.

Weland tried to speak, but could only manage a guttural groan. His eyes were on Ragnar’s sword.

Ragnar offered the blade to me. ‘It’s sharp enough,’ he said, ‘but you’ll be surprised by how much force is needed. An axe would be better.’

Weland looked at me now. His teeth chattered and he twitched. I hated him. I had disliked him from the first, but now I hated him, yet I was still oddly nervous of killing him even though he was already half dead. I have learned that it is one thing to kill in battle, to send a brave man’s soul to the corpse-hall of the gods, but quite another to take a helpless man’s life, and he must have sensed my hesitation for he managed a pitiful plea for his life. ‘I will serve you,’ he said.

‘Make the bastard suffer,’ Ragnar answered for me, ‘send him to the corpse-goddess, but let her know he’s coming by making him suffer.’

I do not think he suffered much. He was already so feeble that even my puny blows drove him to swift unconsciousness, but even so it took a long time to kill him. I hacked away. I have always been surprised by how much effort is needed to kill a man. The skalds make it sound easy, but it rarely is. We are stubborn creatures, we cling to life and are very hard to kill, but Weland’s soul finally went to its fate as I chopped and sawed and stabbed and at last succeeded in severing his bloody head. His mouth was twisted into a rictus of agony, and that was some consolation.

Now I asked more favours of Ragnar, knowing he would give them to me. I took some of the poorer coins from the hoard, then went to one of the larger monastery buildings and found the writing place where the monks copied books. They used to paint beautiful letters on the books and, before my life was changed at Eoferwic, I used to go there with Beocca and sometimes the monks would let me daub scraps of parchment with their wonderful colours.

I wanted the colours now. They were in bowls, mostly as powder, a few mixed with gum, and I needed a piece of cloth which I found in the church; a square of white linen that had been used to cover the sacraments. Back in the writing place I drew a wolf’s head in charcoal on the white cloth and then I found some ink and began to fill in the outline. Brida helped me and she proved to be much better at making pictures than I was, and she gave the wolf a red eye and a red tongue, and flecked the black ink with white and blue that somehow suggested fur, and once the banner was made we tied it to the staff of the dead abbot’s cross. Ragnar was rummaging through the monastery’s small collection of sacred books, tearing off the jewel-studded metal plates that decorated their front covers, and once he had all the plates, and once my banner was made, we burned all the timber buildings.

The rain stopped as we left. We trotted across the causeway, turned south, and Ragnar, at my request, went down the coastal track until we reached the place where the road crossed the sands to Bebbanburg.

We stopped there and I untied my hair so that it hung loose. I gave the banner to Brida who would ride Ravn’s horse while the old man waited with his son. And then, a borrowed sword at my side, I rode home.

Brida came with me as standard-bearer and the two of us cantered along the track. The sea broke white to my right and slithered across the sands to my left. I could see men on the walls and up on the Low Gate, watching, and I kicked the horse, making it gallop, and Brida kept pace, her banner flying above, and I curbed the horse where the track turned north to the gate and now I could see my uncle. He was there, Ælfric the Treacherous, thin-faced, dark-haired, gazing at me from the Low Gate and I stared up at him so he would know who I was, and then I threw Weland’s severed head onto the ground where my brother’s head had once been thrown. I followed it with the silver coins.