По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

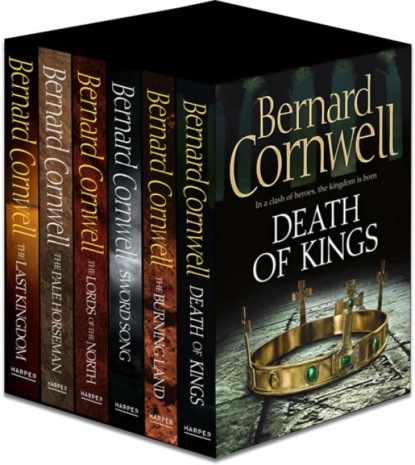

The Last Kingdom Series Books 1-6

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

But we had seen the West Saxons off. And we were still hungry. So it was time to fetch the enemy’s food.

Why did I fight for the Danes? All lives have questions, and that one still haunts me, though in truth there was no mystery. To my young mind the alternative was to be sitting in some monastery learning to read, and give a boy a choice like that and he would fight for the devil rather than scratch on a tile or make marks on a clay tablet. And there was Ragnar, whom I loved, and who sent his three ships across the Temes to find hay and oats stored in Mercian villages and he found just enough so that by the time the army marched westwards our horses were in reasonable condition.

We were marching on Æbbanduna, another frontier town on the Temes between Wessex and Mercia, and, according to our prisoner, a place where the West Saxons had amassed their supplies. Take Æbbanduna and Æthelred’s army would be short of food, Wessex would fall, England would vanish and Odin would triumph.

There was the small matter of defeating the West Saxon army first, but we marched just four days after routing them in front of the walls of Readingum, so we were blissfully confident that they were doomed. Rorik stayed behind, for he was sick again, and the many hostages, like the Mercian twins Ceolberht and Ceolnoth, also stayed in Readingum, guarded there by the small garrison we left to watch over the precious ships.

The rest of us marched or rode. I was among the older of the boys who accompanied the army, our job in battle was to carry the spare shields that could be pushed forward through the ranks in battle. Shields got chopped to pieces in fighting. I have often seen warriors fighting with a sword or axe in one hand, and nothing but the iron shield boss hung with scraps of wood in the other. Brida also came with us, mounted behind Ravn on his horse, and for a time I walked with them, listening as Ravn rehearsed the opening lines of a poem called the Fall of the West Saxons. He had got as far as listing our heroes, and describing how they readied themselves for battle, when one of those heroes, the gloomy Earl Guthrum, rode alongside us. ‘You look well,’ he greeted Ravn in a tone which suggested that was a condition unlikely to last.

‘I cannot look at all,’ Ravn said. He liked puns.

Guthrum, swathed in a black cloak, looked down at the river. We were advancing along a low range of hills and, even in the winter sunlight, the river valley looked lush. ‘Who will be King of Wessex?’ he asked.

‘Halfdan?’ Ravn suggested mischievously.

‘Big kingdom,’ Guthrum said gloomily. ‘Could do with an older man.’ He looked at me sourly. ‘Who’s that?’

‘You forget I am blind,’ Ravn said, ‘so who is who? Or are you asking me which older man you think should be made king? Me, perhaps?’

‘No, no! The boy leading your horse. Who is he?’

‘That is the Earl Uhtred,’ Ravn said grandly, ‘who understands that poets are of such importance that their horses must be led by mere Earls.’

‘Uhtred? A Saxon?’

‘Are you a Saxon, Uhtred?’

‘I’m a Dane,’ I said.

‘And a Dane,’ Ravn went on, ‘who wet his sword at Readingum. Wet it, Guthrum, with Saxon blood.’ That was a barbed comment, for Guthrum’s black-clothed men had not fought outside the walls.

‘And who’s the girl behind you?’

‘Brida,’ Ravn said, ‘who will one day be a skald and a sorceress.’

Guthrum did not know what to say to that. He glowered at his horse’s mane for a few strides, then returned to his original subject. ‘Does Ragnar want to be king?’

‘Ragnar wants to kill people,’ Ravn said. ‘My son’s ambitions are very few; merely to hear jokes, solve riddles, get drunk, give rings, lie belly to belly with women, eat well and go to Odin.’

‘Wessex needs a strong man,’ Guthrum said obscurely. ‘A man who understands how to govern.’

‘Sounds like a husband,’ Ravn said.

‘We take their strongholds,’ Guthrum said, ‘but we leave half their land untouched! Even Northumbria is only half garrisoned. Mercia has sent men to Wessex, and they’re supposed to be on our side. We win, Ravn, but we don’t finish the job.’

‘And how do we do that?’ Ravn asked.

‘More men, more ships, more deaths.’

‘Deaths?’

‘Kill them all!’ Guthrum said with a sudden vehemence, ‘every last one! Not a Saxon alive.’

‘Even the women?’ Ravn asked.

‘We could leave some young ones,’ Guthrum said grudgingly, then scowled at me. ‘What are you looking at, boy?’

‘Your bone, lord,’ I said, nodding at the gold-tipped bone hanging in his hair.

He touched the bone. ‘It’s one of my mother’s ribs,’ he said. ‘She was a good woman, a wonderful woman, and she goes with me wherever I go. You could do worse, Ravn, than make a song for my mother. You knew her, didn’t you?’

‘I did indeed,’ Ravn said blandly. ‘I knew her well enough, Guthrum, to worry that I lack the poetic skills to make a song worthy of such an illustrious woman.’

The mockery flew straight past Guthrum the Unlucky. ‘You could try,’ he said. ‘You could try, and I would pay much gold for a good song about her.’

He was mad, I thought, mad as an owl at midday, and then I forgot him because the army of Wessex was ahead, barring our road and offering battle.

The dragon banner of Wessex was flying on the summit of a long low hill that lay athwart our road. To reach Æbbanduna, which evidently lay a short way beyond the hill and was hidden by it, we would need to attack up the slope and across that ridge of open grassland, but to the north, where the hills fell away to the River Temes, there was a track along the river which suggested we might skirt the enemy position. To stop us he would need to come down the hill and give battle on level ground.

Halfdan called the Danish leaders together and they talked for a long time, evidently disagreeing about what should be done. Some men wanted to attack uphill and scatter the enemy where they were, but others advised fighting the West Saxons in the flat river meadows, and in the end Earl Guthrum the Unlucky persuaded them to do both. That, of course, meant splitting our army into two, but even so I thought it was a clever idea. Ragnar, Guthrum and the two Earls Sidroc would go down to the lower ground, thus threatening to pass by the enemy-held hill, while Halfdan, with Harald and Bagseg, would stay on the high ground and advance towards the dragon banner on the ridge. That way the enemy might hesitate to attack Ragnar for fear that Halfdan’s troops would fall on their rear. Most likely, Ragnar said, the enemy would decide not to fight at all, but instead retreat to Æbbanduna where we could besiege them. ‘Better to have them penned in a fortress than roaming around,’ he said cheerfully.

‘Better still,’ Ravn commented drily, ‘not to divide the army.’

‘They’re only West Saxons,’ Ragnar said dismissively.

It was already afternoon and, because it was winter, the day was short so there was not much time, though Ragnar thought there was more than enough daylight remaining to finish off Æthelred’s troops. Men touched their charms, kissed sword hilts, hefted shields, then we were marching down the hill, going off the chalk grasslands into the river valley. Once there, we were half hidden by the leafless trees, but now and again I could glimpse Halfdan’s men advancing along the hill crests and I could see there were West Saxon troops waiting for them, which suggested that Guthrum’s plan was working and that we could march clear around the enemy’s northern flank. ‘What we do then,’ Ragnar said, ‘is climb up behind them, and the bastards will be trapped. We’ll kill them all!’

‘One of them has to stay alive,’ Ravn said.

‘One? Why?’

‘To tell the tale, of course. Look for their poet. He’ll be handsome. Find him and let him live.’

Ragnar laughed. There were, I suppose, about eight hundred of us, slightly fewer than the contingent that had stayed with Halfdan, and the enemy army was probably slightly larger than our two forces combined, but we were all warriors and many of the West Saxon fyrd were farmers forced to war and so we saw nothing but victory.

Then, as our leading troops marched out of an oakwood, we saw the enemy had followed our example and divided their own army into two. One half was waiting on the hill for Halfdan while the other half had come to meet us.

Alfred led our opponents. I knew that because I could see Beocca’s red hair and, later on, I glimpsed Alfred’s long anxious face in the fighting. His brother, King Æthelred, had stayed on the heights where, instead of waiting for Halfdan to assault him, he was advancing to make his own attack. The Saxons, it seemed, were avid for battle.

So we gave it to them.

Our forces made shield wedges to attack their shield wall. We called on Odin, we howled our war cries, we charged, and the West Saxon line did not break, it did not buckle, but instead held fast and so the slaughter-work began.

Ravn told me time and again that destiny was everything. Fate rules. The three spinners sit at the foot of the tree of life and they make our lives and we are their playthings, and though we think we make our own choices, all our fates are in the spinners’ threads. Destiny is everything, and that day, though I did not know it, my destiny was spun. Wyrd bið ful ãræd, fate is unstoppable.

What is there to say of the battle that the West Saxons said happened at a place they called Æsc’s Hill? I assume Æsc was the thegn who had once owned the land, and his fields received a rich tilth of blood and bone that day. The poets could fill a thousand lines telling what happened, but battle is battle. Men die. In the shield wall it is sweat, terror, cramp, half blows, full blows, screaming and cruel death.

There were really two battles at Æsc’s Hill, the one above and the other below, and the deaths came swiftly. Harald and Bagseg died, Sidroc the Older watched his son die and then was cut down himself, and with him died Earl Osbern and Earl Fraena, and so many other good warriors, and the Christian priests were calling on their god to give the West Saxon swords strength, and that day Odin was sleeping and the Christian god was awake.