По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

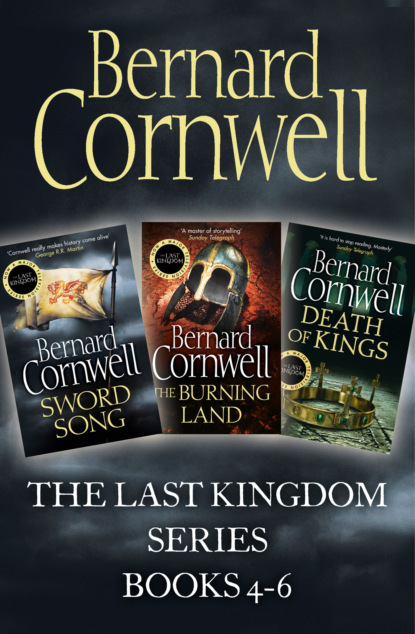

The Last Kingdom Series Books 4-6: Sword Song, The Burning Land, Death of Kings

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Five (#ulink_f1f1867e-9a3d-5fcb-ac5e-d81c38f4734a)

Then all, suddenly, was quiet.

Not really quiet, of course. The river hissed where it ran through the bridge, small waves slapped on the boat hulls, the guttering torches on the house wall crackled and I could hear my men’s footsteps as they clambered ashore. Shields and spear butts thumped on ships’ timbers, dogs barked in the city and somewhere a gander was giving its harsh call, but it seemed quiet. Dawn was now a paler yellow, half concealed by dark clouds.

‘And now?’ Finan appeared beside me. Steapa loomed beside him, but said nothing.

‘We go to the gate,’ I said, ‘Ludd’s Gate.’ But I did not move. I did not want to move. I wanted to be back at Coccham with Gisela. It was not cowardice. Cowardice is always with us, and bravery, the thing that provokes the poets to make their songs about us, is merely the will to overcome the fear. It was tiredness that made me reluctant to move, but not a physical tiredness. I was young then and the wounds of war had yet to sap my strength. I think I was tired of Wessex, tired of fighting for a king I did not like, and, standing on that Lundene wharf, I did not understand why I fought for him. And now, looking back over the years, I wonder if that lassitude was caused by the man I had just killed and whom I had promised to join in Odin’s hall. I believe the men we kill are inseparably joined to us. Their life threads, turned ghostly, are twisted by the Fates around our own thread and their burden stays to haunt us till the sharp blade cuts our life at last. I felt remorse for his death.

‘Are you going to sleep?’ Father Pyrlig asked me. He had joined Finan.

‘We’re going to the gate,’ I said.

It seemed like a dream. I was walking, but my mind was somewhere else. This, I thought, was how the dead walked our world, for the dead do come back. Not as Bjorn had pretended to come back, but in the darkest nights, when no one alive can see them, they wander our world. They must, I thought, only half see it, as if the places they knew were veiled in a winter mist, and I wondered if my father was watching me. Why did I think that? I had not been fond of my father, nor he of me, and he had died when I was young, but he had been a warrior. The poets sang of him. And what would he think of me? I was walking through Lundene instead of attacking Bebbanburg, and that was what I should have done. I should have gone north. I should have spent my whole hoard of silver on hiring men and leading them in an assault across Bebbanburg’s neck of land and up across the walls to the high hall where we could make great slaughter. Then I could live in my own home, my father’s home, for ever. I could live near Ragnar and be far from Wessex.

Except my spies, for I employed a dozen in Northumbria, had told me what my uncle had done to my fortress. He had closed the landside gates. He had taken them away altogether and in their place were ramparts, newly built, high and reinforced with stone, and now, if a man wished to get inside the fortress, he needed to follow a path that led to the northern end of the crag on which the fortress stood. And every step of that path would be under those high walls, under attack, and then, at the northern end, where the sea broke and sucked, there was a small gate. Beyond that gate was a steep path leading to another wall and another gate. Bebbanburg had been sealed, and to take it I would need an army beyond even the reach of my hoarded silver.

‘Be lucky!’ a woman’s voice startled me from my thoughts. The folk of the old city were awake and they saw us pass and took us for Danes because I had ordered my men to hide their crosses.

‘Kill the Saxon bastards!’ another voice shouted.

Our footsteps echoed from the high houses that were all at least three storeys tall. Some had beautiful stonework over their bricks and I thought how the world had once been filled with these houses. I remember the first time I ever climbed a Roman staircase, and how odd it felt, and I knew that in times gone by men must have taken such things for granted. Now the world was dung and straw and damp-ridden wood. We had stone masons, of course, but it was quicker to build from wood, and the wood rotted, but no one seemed to care. The whole world rotted as we slid from light into darkness, getting ever nearer to the black chaos in which this middle world would end and the gods would fight and all love and light and laughter would dissolve. ‘Thirty years,’ I said aloud.

‘Is that how old you are?’ Father Pyrlig asked me.

‘It’s how long a hall lasts,’ I said, ‘unless you keep repairing it. Our world is falling apart, father.’

‘My God, you’re gloomy,’ Pyrlig said, amused.

‘And I watch Alfred,’ I went on, ‘and see how he tries to tidy our world. Lists! Lists and parchment! He’s like a man putting wattle hurdles in the face of a flood.’

‘Brace a hurdle well,’ Steapa was listening to our conversation and now intervened, ‘and it’ll turn a stream.’

‘And better to fight a flood than drown in it,’ Pyrlig commented.

‘Look at that!’ I said, pointing to the carved stone head of a beast that was fixed to a brick wall. The beast was like none I had ever seen, a shaggy great cat, and its open mouth was poised above a chipped stone basin suggesting that water had once flowed from mouth to bowl. ‘Could we make that?’ I asked bitterly.

‘There are craftsmen who can make such things,’ Pyrlig said.

‘Then where are they?’ I demanded angrily, and I thought that all these things, the carvings and bricks and marble, had been made before Pyrlig’s religion came to the island. Was that the reason for the world’s decay? Were the true gods punishing us because so many men worshipped the nailed god? I did not make the suggestion to Pyrlig, but kept silent. The houses loomed above us, except where one had collapsed into a heap of rubble. A dog rooted along a wall, stopped to cock its leg, then turned a snarl on us. A baby cried in a house. Our footsteps echoed from the walls. Most of my men were silent, wary of the ghosts they believed inhabited these relics of an older time.

The baby wailed again, louder. ‘Be a young mother in there,’ Rypere said happily. Rypere was his nickname and meant ‘thief’, and he was a skinny Angle from the north, clever and sly, and he at least was not thinking of ghosts.

‘I should stick to goats, if I were you,’ Clapa said, ‘they don’t mind your stink.’ Clapa was a Dane, one who had taken an oath to me and served me loyally. He was a hulking great boy raised on a farm, strong as an ox, ever cheerful. He and Rypere were friends who never stopped goading each other.

‘Quiet!’ I said before Rypere could make a retort. I knew we had to be getting close to the western walls. At the place where we had come ashore, the city climbed the wide terraced hill to the palace at the top, but that hill was flattening now, which meant we were nearing the valley of the Fleot. Behind us the sky was lightening to morning and I knew Æthelred would think I had failed to make my feint attack just before the dawn and that belief, I feared, might have persuaded him to abandon his own assault. Perhaps he was already leading his men back to the island? In which case we would be alone, surrounded by our enemies, and doomed.

‘God help us,’ Pyrlig suddenly said.

I held up my hand to stop my men because, in front of us, in the last stretch of the street before it passed under the stone arch called Ludd’s Gate, was a crowd of men. Armed men. Men whose helmets, axe blades and spear-points caught and reflected the dull light of the clouded and newly-risen sun.

‘God help us,’ Pyrlig said again and made the sign of the cross. ‘There must be two hundred of them.’

‘More,’ I said. There were so many men that they could not all stand in the street, forcing some into the alleyways on either side. All the men we could see were facing the gate, and that made me understand what the enemy was doing and my mind cleared at that instant as if a fog had lifted. There was a courtyard to my left and I pointed through its gateway. ‘In there,’ I ordered.

I remember a priest, a clever fellow, visiting me to ask for my memories of Alfred, which he wanted to put in a book. He never did, because he died of the flux shortly after he saw me, but he was a shrewd man and more forgiving than most priests, and I recall how he asked me to describe the joy of battle. ‘My wife’s poets will tell you,’ I said to him.

‘Your wife’s poets never fought,’ he pointed out, ‘and they just take songs about other heroes and change the names.’

‘They do?’

‘Of course they do,’ he had said, ‘wouldn’t you, lord?’

I liked that priest and so I talked to him, and the answer I eventually gave him was that the joy of battle was the delight of tricking the other side. Of knowing what they will do before they do it, and having the response ready so that, when they make the move that is supposed to kill you, they die instead. And at that moment, in the damp gloom of the Lundene street, I knew what Sigefrid was doing and knew too, though he did not know it, that he was giving me Ludd’s Gate.

The courtyard belonged to a stone-merchant. His quarries were Lundene’s Roman buildings and piles of dressed masonry were stacked against the walls ready to be shipped to Frankia. Still more stones were heaped against the gate that led through the river wall to the wharves. Sigefrid, I thought, must have feared an assault from the river and had blocked every gate through the walls west of the bridge, but he had never dreamed anyone would shoot the bridge to the unguarded eastern side. But we had, and my men were hidden in the courtyard while I stood in the entrance and watched the enemy throng at Ludd’s Gate.

‘We’re hiding?’ Osferth asked me. His voice had a whine to it, as if he were perpetually complaining.

‘There are hundreds of men between us and the gate,’ I explained patiently, ‘and we are too few to cut through them.’

‘So we failed,’ he said, not as a question, but as a petulant statement.

I wanted to hit him, but managed to stay patient. ‘Tell him,’ I said to Pyrlig, ‘what is happening.’

‘God in his wisdom,’ the Welshman explained, ‘has persuaded Sigefrid to lead an attack out of the city! They’re going to open that gate, boy, and stream across the marshes, and hack their way into Lord Æthelred’s men. And as most of Lord Æthelred’s men are from the fyrd, and most of Sigefrid’s are real warriors, then we all know what’s going to happen!’ Father Pyrlig touched his mail coat where the wooden cross was hidden. ‘Thank you, God!’

Osferth stared at the priest. ‘You mean,’ he said after a pause, ‘that Lord Æthelred’s men will be slaughtered?’

‘Some of them are going to die!’ Pyrlig allowed cheerfully, ‘and I hope to God they die in grace, boy, or they’ll never hear that heavenly choir, will they?’

‘I hate choirs,’ I growled.

‘No, you don’t,’ Pyrlig said. ‘You see, boy,’ he looked back to Osferth, ‘once they’ve gone out of the gate, then there’ll only be a handful of men guarding it. So that’s when we attack! And Sigefrid will suddenly find himself with an enemy in front and another one behind, and that predicament can make a man wish he’d stayed in bed.’

A shutter opened in one of the high windows over the courtyard. A young woman stared out at the lightening sky, then stretched her hands high and yawned hugely. The gesture stretched her linen shift tight across her breasts, then she saw my men beneath her and instinctively clutched her arms to her chest. She was clothed, but must have felt naked. ‘Oh, thank you dear Saviour for another sweet mercy,’ Pyrlig said, watching her.

‘But if we take the gate,’ Osferth said, worrying at the problems he saw, ‘the men left in the city will attack us.’

‘They will,’ I agreed.

‘And Sigefrid …’ he began.

‘Will probably turn back to slaughter us,’ I finished his sentence for him.

‘So?’ he said, then checked, because he saw nothing but blood and death in his future.

‘It all depends,’ I said, ‘on my cousin. If he comes to our aid then we should win. If he doesn’t?’ I shrugged, ‘then keep good hold of your sword.’