По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

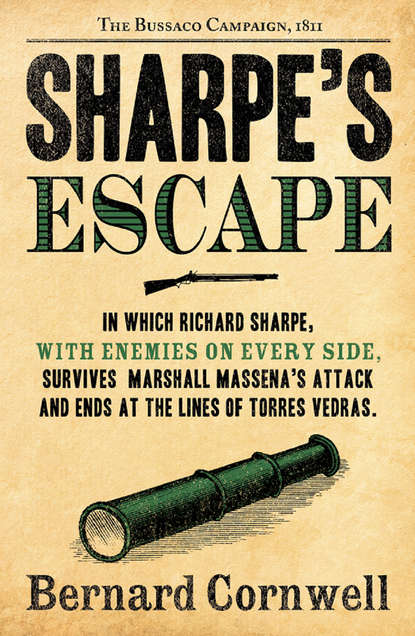

Sharpe’s Escape: The Bussaco Campaign, 1810

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Ferragus towered over Sharpe. ‘Your work is done here, Captain. The tower is no more, so you may go.’

Sharpe stepped back out of the huge man’s shadow, sideways to get around him and then went to the shrine and heard the distinctive sound of the volley gun’s ratchet scraping as Harper cocked it. ‘Careful, now,’ the Irishman said, ‘it only takes a tremor for this bastard to go off and it would make a terrible mess of your shirt, sir.’ Ferragus had plainly turned to intercept Sharpe, but the huge gun checked him.

The shrine door was unlocked. Sharpe pushed it open and it took a moment for his eyes to adjust from the bright sunlight to the shrine’s black shadows, but then he saw what was inside and swore.

He had expected a bare country shrine like the dozens of others he had seen, but instead the small building was heaped with sacks, so many sacks that the only space left was a narrow passage leading to a crude altar on which a blue-gowned image of the Virgin Mary was festooned with little slips of paper left by desperate peasants who came to the hilltop in search of a miracle. Now the Virgin gazed sadly on the sacks as Sharpe drew his sword and stabbed one. He was rewarded by a trickle of flour. He tried another sack further down and still more flour sifted to the bare earth floor. Ferragus had seen what Sharpe had done and harangued Ferreira who, reluctantly, came into the shrine. ‘The flour is here with my government’s knowledge,’ the Major said.

‘You can prove that?’ Sharpe asked. ‘Got a piece of paper, have you?’

‘It is the business of the Portuguese government,’ Ferreira said stiffly, ‘and you will leave.’

‘I have orders,’ Sharpe countered. ‘We all have orders. There’s to be no food left for the French. None.’ He stabbed another sack, then turned as Ferragus came into the shrine, his bulk shadowing the doorway. He moved ominously down the narrow passage between the sacks, filling it, and Sharpe suddenly coughed loudly and scuffed his feet as Ferreira squeezed into the sacks to let Ferragus past.

The huge man held out a hand to Sharpe. He was holding coins, gold coins, maybe a dozen thick gold coins, bigger than English guineas and probably adding up to three years’ salary for Sharpe. ‘You and I can talk,’ Ferragus said.

‘Sergeant Harper!’ Sharpe called past the looming Ferragus. ‘What are those bloody Crapauds doing?’

‘Keeping their distance, sir. Staying well off, they are.’

Sharpe looked up at Ferragus. ‘You’re not surprised there are French dragoons coming, are you? Expecting them, were you?’

‘I am asking you to go,’ Ferragus said, moving closer to Sharpe. ‘I am being polite, Captain.’

‘Hurts, don’t it?’ Sharpe said. ‘And what if I don’t go? What if I obey my orders, senhor, and get rid of this food?’

Ferragus was plainly unused to being challenged for he seemed to shiver, as if forcing himself to be calm. ‘I can reach into your little army, Captain,’ he said in his deep voice, ‘and I can find you, and I can make you regret today.’

‘Are you threatening me?’ Sharpe asked in astonishment. Major Ferreira, behind Ferragus, made some soothing noises, but both men ignored him.

‘Take the money,’ Ferragus said.

When Sharpe had coughed and scuffed his feet he had been making enough noise to smother the sound of his rifle being cocked. It hung from his right shoulder, the muzzle just behind his ear, and now he moved his right hand back to the trigger. He looked down at the coins and Ferragus must have thought he had tempted Sharpe for he thrust the gold closer, and Sharpe looked up into his eyes and pressed the trigger.

The shot slammed into the roof tiles and filled the shrine with smoke and noise. The sound deafened Sharpe and it distracted Ferragus for half a second, the half second in which Sharpe brought up his right knee into the big man’s groin, following it with a thrust of his left hand, fingers rigid, into Ferragus’s eyes and then his right hand, knuckles clenched, into his Adam’s apple. He reckoned he had stood no chance in a fair fight, but Sharpe, like Ferragus, reckoned fair fights were for fools. He knew he had to put Ferragus down fast and hurt him so bad that the huge man could not fight back, and he had done it in a heartbeat, for the big man was bent over, filled with pain and fighting for breath, and Sharpe cleared him from the passage by dragging him into the space in front of the altar and then walked past a horrified Ferreira. ‘You got anything to say to me, Major?’ Sharpe asked, and when Ferreira dumbly shook his head Sharpe made his way back into the sunlight. ‘Lieutenant Slingsby!’ he called. ‘What are those damned dragoons doing?’

‘Keeping their distance, Sharpe,’ Slingsby said. ‘What was that shot?’

‘I was showing a Portuguese fellow how a rifle works,’ Sharpe said. ‘How much distance?’

‘At least half a mile. Bottom of the hill.’

‘Watch them,’ Sharpe said, ‘and I want thirty men in here now. Mister Iliffe! Sergeant McGovern!’

He left Ensign Iliffe in nominal charge of the thirty men who were to haul the sacks out of the shrine. Once outside, the sacks were slit open and their contents scattered across the hilltop. Ferragus came limping from the shrine and his men looked confused and angry, but they were hugely outnumbered and there was nothing they could do. Ferragus had regained his breath, though he was having trouble standing upright. He spoke bitterly to Ferreira, but the Major managed to talk some sense into the big man and, at last, they all mounted their horses and, with a last resentful look at Sharpe, rode down the westwards track.

Sharpe watched them retreat then went to join Slingsby. Behind him the telegraph tower burned fierce, suddenly keeling over with a great splintering noise and an explosion of sparks. ‘Where are the Crapauds?’

‘In that gully.’ Slingsby pointed to a patch of dead ground near the bottom of the hill. ‘Dismounted now.’

Sharpe used his telescope and saw two of the green-uniformed men crouching behind boulders. One of them had a telescope and was watching the hilltop and Sharpe gave the man a cheerful wave. ‘Not much bloody use there, are they?’ he said.

‘They could be planning to attack us,’ Slingsby suggested eagerly.

‘Not unless they’re tired of life,’ Sharpe said, reckoning the dragoons had been beckoned westwards by the white flag on the telegraph tower, and now that the flag had been replaced by a plume of smoke they were undecided what to do. He trained his glass further south and saw there was still gun smoke in the valley where the main road ran beside the river. The rearguard was evidently holding its own, but they would have to retreat soon for, further east, he could now see the main enemy army that showed as dark columns marching in fields. They were a very long way off, scarcely visible even through the glass, but they were there, a shadowed horde coming to drive the British out of central Portugal. L’Armée de Portugal, the French called it, the army that was meant to whip the redcoats clear to Lisbon, then out to sea, so that Portugal would at last be placed under the tricolour, but the army of Portugal was in for a surprise. Marshal Masséna would march into an empty land and then find himself facing the Lines of Torres Vedras.

‘See anything, Sharpe?’ Slingsby stepped closer, plainly wanting to borrow the telescope.

‘Have you been drinking rum?’ Sharpe asked, again getting a whiff of the spirit.

Slingsby looked alarmed, then offended. ‘Put it on the skin,’ he said gruffly, slapping his face, ‘to keep off the flies.’

‘You do what?’

‘Trick I learned in the islands.’

‘Bloody hell,’ Sharpe said, then collapsed the glass and put it into his pocket. ‘There are Frogs over there,’ he said, pointing southeast, ‘thousands of goddamn bloody Frogs.’

He left the Lieutenant gazing at the distant army and went back to chivvy the redcoats who had formed a chain to sling the sacks out onto the hillside which now looked as though it were ankle deep in snow. Flour drifted like powder smoke from the summit, fell softly, made mounds, and still more sacks were hurled out the door. Sharpe reckoned it would take a couple of hours to empty the shrine. He ordered ten riflemen to join the work and sent ten of the redcoats to join Slingsby’s picquet. He did not want his redcoats to start whining that they did all the work while the riflemen got the easy jobs. Sharpe gave them a hand himself, standing in the line and tossing sacks through the door as the collapsed telegraph burned itself out, its windblown cinders staining the white flour with black spots.

Slingsby came just as the last sacks were being destroyed. ‘Dragoons have gone, Sharpe,’ he reported. ‘Reckon they saw us and rode off.’

‘Good.’ Sharpe forced himself to sound civil, then went to join Harper who was watching the dragoons ride away. ‘They didn’t want to play with us, Pat?’

‘Then they’ve more sense than that big Portuguese fellow,’ Harper said. ‘Give him a headache, did you?’

‘Bastard wanted to bribe me.’

‘Oh, it’s a wicked world,’ Harper said, ‘and there’s me always dreaming of getting a wee bribe.’ He slung the seven-barrel gun on his shoulder. ‘So what were those fellows doing up here?’

‘No good,’ Sharpe said, brushing his hands before pulling on his mended jacket that was now smeared with flour. ‘Mister bloody Ferragus was selling that flour to the Crapauds, Pat, and that bloody Portuguese Major was in it up to his arse.’

‘Did they tell you that now?’

‘Of course they didn’t,’ Sharpe said, ‘but what else were they doing? Jesus! They were flying a white flag to tell the Frogs it was safe up here and if we hadn’t arrived, Pat, they’d have sold that flour.’

‘God and his saints preserve us from evil,’ Harper said in amusement, ‘and it’s a pity the dragoons didn’t come up to play.’

‘Pity! Why the hell would we want a fight for no purpose?’

‘Because you could have got yourself one of their horses, sir,’ Harper said, ‘of course.’

‘And why would I want a bloody horse?’

‘Because Mister Slingsby’s getting one, so he is. Told me so himself. The Colonel’s giving him a horse, he is.’

‘No bloody business of mine,’ Sharpe said, but the thought of Lieutenant Slingsby on a horse nevertheless annoyed him. A horse, whether Sharpe wanted one or not, was a symbol of status. Bloody Slingsby, he thought, and stared at the distant hills and saw how low the sun had sunk. ‘Let’s go home,’ he said.

‘Yes, sir,’ Harper said. He knew precisely why Mister Sharpe was in a bad mood, but he could not say as much. Officers were supposed to be brothers in arms, not blood enemies.