По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

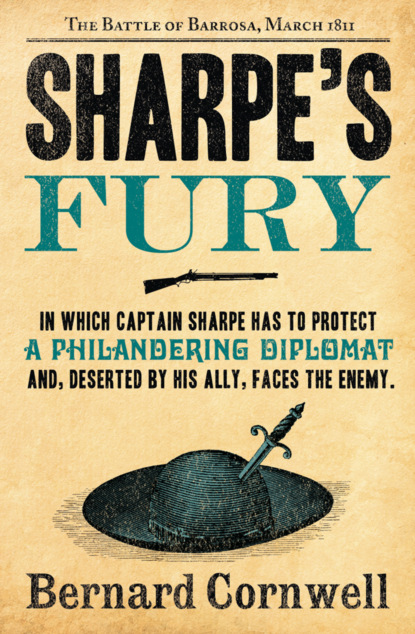

Sharpe’s Fury: The Battle of Barrosa, March 1811

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Lecroix ignored the scorn. ‘Or do you intend to leave our wounded for the amusements of the Portuguese?’

Sharpe was tempted to say that any French wounded deserved whatever they got from the Portuguese, but he resisted the urge. The request, he reckoned, was fair enough and so he drew Jack Bullen away far enough so that the French officers could not overhear him. ‘Go and see the brigadier,’ he told the lieutenant, ‘and tell him these buggers want to fetch their wounded over the river before we destroy the bridge.’

Bullen set off back across the bridge while two of the French officers started back towards Fort Josephine, followed by all the women except the two Spaniards who, barefoot and ragged, hurried south down the river’s bank. Lecroix watched them go. ‘Those two didn’t want to stay with us?’ He sounded surprised.

‘They said you captured them.’

‘We probably did.’ He took out a leather case of long thin cigars and offered one to Sharpe. Sharpe shook his head, then waited as Lecroix laboriously struck a light with his tinderbox. ‘You did well this morning,’ the Frenchman said once the cigar was alight.

‘Your garrison was asleep,’ Sharpe said.

Lecroix shrugged. ‘Garrison troops. No good. Old and sick and tired men.’ He spat out a shred of tobacco. ‘But I think you have done all the damage you will do today. You will not break the bridge.’

‘We won’t?’

‘Cannon,’ Lecroix said laconically, gesturing at Fort Josephine, ‘and my colonel is determined to preserve the bridge, and what my colonel wants, he gets.’

‘Colonel Vandal?’

‘Vandal,’ Lecroix corrected Sharpe’s pronunciation. ‘Colonel Vandal of the eighth of the line. You have heard of him?’

‘Never.’

‘You should educate yourself, Captain,’ Lecroix said with a smile, ‘read the accounts of Austerlitz and be astonished by Colonel Vandal’s bravery.’

‘Austerlitz?’ Sharpe asked. ‘What was that?’

Lecroix just shrugged. The women’s luggage was dropped at the bridge’s end and Sharpe sent the men back, then followed them until he reached Lieutenant Sturridge who was kicking at the planks on the foredeck of the fourth pontoon from the bank. The timber was rotten and he had managed to make a hole there. The stench of stagnant water came from the hole. ‘If we widen it,’ Sturridge said, ‘then we should be able to blow this one to hell and beyond.’

‘Sir!’ Harper called and Sharpe turned eastwards and saw French infantry coming from Fort Josephine. They were fixing bayonets and forming ranks just outside the fort, but he had no doubt they were coming to the bridge. It was a big company, at least a hundred men. French battalions were divided into six companies, unlike the British who had ten, and this company looked formidable with fixed bayonets. Bloody hell, Sharpe thought, but if the Frogs wanted to make a fight of it then they had better hurry because Sturridge, helped by half a dozen of Sharpe’s men, was prising off the pontoon’s foredeck and Harper was carrying the first powder barrel towards the widening hole.

There was a thunderous sound from the Portuguese side of the bridge and Sharpe saw the brigadier, accompanied by two officers, galloping onto the roadway. More redcoats were coming from the fort, doubling down the stony track, evidently to reinforce Sharpe’s men. The brigadier’s commandeered stallion was nervous of the vibrating roadway, but Moon was a superb horseman and kept the beast under control. He curbed the horse close to Sharpe. ‘What the devil’s going on?’

‘They said they wanted to fetch their wounded, sir.’

‘So what are those bloody men doing?’ Moon looked at the French infantry.

‘I reckon they want to stop us blowing the bridge, sir.’

‘Damn them to hell,’ Moon said, throwing Sharpe an angry look as if it was Sharpe’s fault. ‘Either they’re talking to us or they’re fighting us, they can’t do both at the same time! There are some bloody rules in war!’ He spurred on. Major Gillespie, the brigadier’s aide, followed him after giving Sharpe a sympathetic glance. The third horseman was Jack Bullen. ‘Come on, Bullen!’ Moon shouted. ‘You can interpret for me. My Frog ain’t up to scratch.’

Harper was filling the bows of the fourth pontoon with the barrels and Sturridge had taken off his jacket and was unwinding the slow match coiled about his waist. There was nothing there for Sharpe to do, so he went to where the brigadier was snarling at Lecroix. The immediate cause of the brigadier’s anger was that the French infantry company had advanced halfway down the hill and were now arrayed in line facing the bridge. They were no more than a hundred paces away, and were accompanied by three mounted officers. ‘You can’t talk to us about recovering your wounded and make threatening movements at the same time!’ Moon snapped.

‘I believe, monsieur, those men merely come to collect the wounded,’ Lecroix said soothingly.

‘Not carrying weapons, they don’t,’ Moon said, ‘and not without my permission! And why the hell have they got fixed bayonets?’

‘A misunderstanding, I’m sure,’ Lecroix said emolliently. ‘Perhaps you would do us the honour of discussing the matter with my colonel?’ He gestured towards the horsemen waiting behind the French infantry.

But Moon was not going to be summoned by some French colonel. ‘Tell him to come here,’ he insisted.

‘Or you will send an emissary, perhaps?’ Lecroix suggested smoothly, ignoring the brigadier’s direct order.

‘Oh, for God’s sake,’ Moon growled. ‘Major Gillespie? Go and talk sense to the damned man. Tell him he can send one officer and twenty soldiers to recover their wounded. They’re not to bring any weapons, but the officer may carry sidearms. Lieutenant?’ The brigadier looked at Bullen. ‘Go and translate.’

Gillespie and Bullen rode uphill with Lecroix. Meanwhile the light company of the 88th had arrived on the French side of the bridge that was now crowded with soldiers. Sharpe was worried. His own company was on the roadway, guarding Sturridge, and now the 88th’s light company had joined them, and they all made a prime target for the French company which was in a line of three ranks. Then there were the French gunners watching from the ramparts of Fort Josephine who doubtless had their barrels loaded with grapeshot. Moon had ordered the 88th down to the bridge, but now seemed to realize that they were an embarrassment rather than a reinforcement. ‘Take your men back to the other side,’ he called to their captain, then turned around because a single Frenchman was now riding towards the bridge. Gillespie and Bullen, meanwhile, were with the other French officers behind the enemy company.

The French officer curbed his horse twenty paces away and Sharpe assumed this was the renowned Colonel Vandal, the 8th’s commanding officer, for he had two heavy gold epaulettes on his blue coat and his cocked hat was crowned with a white pom-pom which seemed a frivolous decoration for a man who looked so baleful. He had a savagely unfriendly face with a narrow black moustache. He appeared to be about Sharpe’s age, in his middle thirties, and had a force that came from an arrogant confidence. He spoke good English in a clipped harsh voice. ‘You will withdraw to the far bank,’ he said without any preamble.

‘And who the devil are you?’ Moon demanded.

‘Colonel Henri Vandal,’ the Frenchman said, ‘and you will withdraw to the far bank and leave the bridge undamaged.’ He took a watch from his coat pocket, clicked open the lid and showed the face to the brigadier. ‘I shall give you one minute before I open fire.’

‘This is no way to behave,’ Moon said loftily. ‘If you wish to fight, Colonel, then you will have the courtesy to return my envoys first.’

‘Your envoys?’ Vandal seemed amused by the word. ‘I saw no flag of truce.’

‘Your fellow didn’t carry one either!’ Moon protested.

‘And Captain Lecroix reports that you brought your gunpowder with our women. I could not stop you, of course, without killing women. You risked the women’s lives, I did not, so I assume you have abandoned the rules of civilized warfare. I shall, however, return your officers when you withdraw from the undamaged bridge. You have one minute, monsieur.’ And with those words Vandal turned his horse and spurred it back up the track.

‘Are you holding my men prisoner?’ Moon shouted.

‘I am!’ Vandal called back carelessly.

‘There are rules of warfare!’ Moon shouted at the retreating colonel.

‘Rules?’ Vandal turned his horse and his handsome, arrogant face showed disdain. ‘You think there are rules in war? You think it is like your English game of cricket?’

‘Your fellow asked us to send an emissary,’ Moon said hotly. ‘We did. There are rules governing such matters. Even you French should know that.’

‘We French,’ Vandal said, amused. ‘I shall tell you the rules, monsieur. I have orders to cross the bridge with a battery of artillery. If there is no bridge, I cannot cross the river. So my rule is that I shall preserve the bridge. In short, monsieur, there is only one rule in warfare, and that is to win. Other than that, monsieur, we French have no rules.’ He turned his horse and spurred uphill. ‘You have one minute,’ he called back carelessly.

‘Good God incarnate,’ Moon said, staring after the Frenchman. The brigadier was plainly puzzled, even astonished by Vandal’s ruthlessness. ‘There are rules!’ he protested into thin air.

‘Blow the bridge, sir?’ Sharpe asked stolidly.

Moon was still gazing after Vandal. ‘They invited us to talk! The bloody man invited us to talk! They can’t do this. There are rules!’

‘You want us to blow the bridge, sir?’ Sharpe asked again.

Moon appeared not to hear. ‘He has to return Gillespie and your lieutenant,’ he said. ‘God damn it, there are rules!’

‘He’s not going to return them, sir,’ Sharpe said.

Moon frowned from the saddle. He appeared puzzled, as if he did not know how he was to deal with Vandal’s treachery. ‘He can’t keep them prisoner!’ he protested.

‘He’s going to keep them, sir, unless you tell me to leave the bridge intact.’