По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

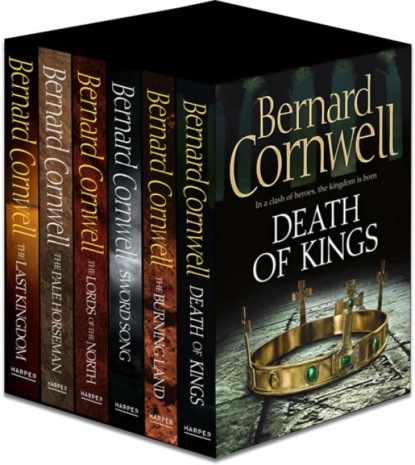

The Last Kingdom Series Books 1-6

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Chapter One (#u7349ddd6-1d04-5730-86d2-4d5a1fb69ed8)

Chapter Two (#u04bbd518-e7ca-594c-8ae9-c535e5a3fd53)

Chapter Three (#ub986e542-aa9b-565d-a7a2-25aa627f3854)

Part Two: THE SWAMP KING (#ufc493c29-c10a-52f6-a84b-776266c222b9)

Chapter Four (#ue4c87d0f-92f5-5f21-a305-242feda151f7)

Chapter Five (#u14f681b8-d383-5620-abf1-209b25649714)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Part Three: THE FYRD (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Historical Note (#litres_trial_promo)

PLACE-NAMES (#ulink_b8968a04-462d-5ee6-8b28-6537dcfa3059)

The spelling of place-names in Anglo-Saxon England was an uncertain business, with no consistency and no agreement even about the name itself. Thus London was variously rendered as Lundonia, Lundenberg, Lundenne, Lundene, Lundenwic, Lundenceaster and Lundres. Doubtless some readers will prefer other versions of the names listed below, but I have usually employed whichever spelling is cited in the Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names for the years nearest or contained within Alfred’s reign, 871–899 AD, but even that solution is not foolproof. Hayling Island, in 956, was written as both Heilincigae and Hæglingaiggæ. Nor have I been consistent myself; I use England instead of Englaland, and have preferred the modern form Northumbria to Norðhymbralond to avoid the suggestion that the boundaries of the ancient kingdom coincide with those of the modern county. So this list, like the spellings themselves, is capricious.

PART ONE (#ulink_809b1274-25c1-5fe7-925c-a2e247a0b6cb)

Viking (#ulink_809b1274-25c1-5fe7-925c-a2e247a0b6cb)

One (#ulink_9207328f-0a13-5a05-825a-07b3d4861747)

These days I look at twenty-year-olds and think they are pathetically young, scarcely weaned from their mothers’ tits, but when I was twenty I considered myself a full-grown man. I had fathered a child, fought in the shield wall, and was loath to take advice from anyone. In short I was arrogant, stupid and headstrong. Which is why, after our victory at Cynuit, I did the wrong thing.

We had fought the Danes beside the ocean, where the river runs from the great swamp and the Sæfern Sea slaps on a muddy shore, and there we had beaten them. We had made a great slaughter and I, Uhtred of Bebbanburg, had done my part. More than my part, for at the battle’s end, when the great Ubba Lothbrokson, most feared of all the Danish leaders, had carved into our shield wall with his great war axe, I had faced him, beaten him and sent him to join the einherjar, that army of the dead who feast and swive in Odin’s corpse-hall.

What I should have done then, what Leofric told me to do, was ride hard to Exanceaster where Alfred, King of the West Saxons, was besieging Guthrum. I should have arrived deep in the night, woken the king from his sleep and laid Ubba’s battle banner of the black raven and Ubba’s great war axe, its blade still crusted with blood, at Alfred’s feet. I should have given the king the good news that the Danish army was beaten, that the few survivors had taken to their dragon-headed ships, that Wessex was safe and that I, Uhtred of Bebbanburg, had achieved all of those things.

Instead I rode to find my wife and child.

At twenty years old I would rather have been ploughing Mildrith than reaping the reward of my good fortune, and that is what I did wrong, but, looking back, I have few regrets. Fate is inexorable, and Mildrith, though I had not wanted to marry her and though I came to detest her, was a lovely field to plough.

So, in that late spring of the year 877, I spent the Saturday riding to Cridianton instead of going to Alfred. I took twenty men with me and I promised Leofric that we would be at Exanceaster by midday on Sunday and I would make certain Alfred knew we had won his battle and saved his kingdom.

‘Odda the Younger will be there by now,’ Leofric warned me. Leofric was almost twice my age, a warrior hardened by years of fighting the Danes. ‘Did you hear me?’ he asked when I said nothing. ‘Odda the Younger will be there by now,’ he said again, ‘and he’s a piece of goose shit who’ll take all the credit.’

‘The truth cannot be hidden,’ I said loftily.

Leofric mocked that. He was a bearded squat brute of a man who should have been the commander of Alfred’s fleet, but he was not well-born and Alfred had reluctantly given me charge of the twelve ships because I was an ealdorman, a noble, and it was only fitting that a high-born man should command the West Saxon fleet even though it had been much too puny to confront the massive array of Danish ships that had come to Wessex’s south coast. ‘There are times,’ Leofric grumbled, ‘when you are an earsling.’ An earsling was something that had dropped out of a creature’s backside and was one of Leofric’s favourite insults. We were friends.

‘We’ll see Alfred tomorrow,’ I said.

‘And Odda the Younger,’ Leofric said patiently, ‘has seen him today.’

Odda the Younger was the son of Odda the Elder who had given my wife shelter, and the son did not like me. He did not like me because he wanted to plough Mildrith, which was reason enough for him to dislike me. He was also, as Leofric said, a piece of goose shit, slippery and slick, which was reason enough for me to dislike him.

‘We shall see Alfred tomorrow,’ I said again, and next morning we all rode to Exanceaster, my men escorting Mildrith, our son and his nurse, and we found Alfred on the northern side of Exanceaster where his green and white dragon banner flew above his tents. Other banners snapped in the damp wind, a colourful array of beasts, crosses, saints and weapons announcing that the great men of Wessex were with their king. One of those banners showed a black stag, which confirmed that Leofric had been right and that Odda the Younger was here in south Defnascir. Outside the camp, between its southern margin and the city walls, was a great pavilion made of sail-cloth stretched across guyed poles, and that told me that Alfred, instead of fighting Guthrum, was talking to him. They were negotiating a truce, though not on that day, for it was a Sunday and Alfred would do no work on a Sunday if he could help it. I found him on his knees in a makeshift church made from another poled sail-cloth, and all his nobles and thegns were arrayed behind him, and some of those men turned as they heard our horses’ hooves. Odda the Younger was one of those who turned and I saw the apprehension show on his narrow face.

The bishop who was conducting the service paused to let the congregation make a response, and that gave Odda an excuse to look away from me. He was kneeling close to Alfred, very close, suggesting that he was high in the king’s favour, and I did not doubt that he had brought the dead Ubba’s raven banner and war axe to Exanceaster and claimed the credit for the fight beside the sea. ‘One day,’ I said to Leofric, ‘I shall slit that bastard from the crotch to the gullet and dance on his offal.’

‘You should have done it yesterday.’

A priest had been kneeling close to the altar, one of the many priests who always accompanied Alfred, and he saw me and slid backwards as unobtrusively as he could until he was able to stand and hurry towards me. He had red hair, a squint, a palsied left hand and an expression of astonished joy on his ugly face. ‘Uhtred!’ he called as he ran towards our horses, ‘Uhtred! We thought you were dead!’

‘Me?’ I grinned at the priest. ‘Dead?’

‘You were a hostage!’

I had been one of the dozen English hostages in Werham, but while the others had been murdered by Guthrum, I had been spared because of Earl Ragnar who was a Danish war-chief and as close to me as a brother. ‘I didn’t die, father,’ I said to the priest, whose name was Beocca, ‘and I’m surprised you did not know that.’

‘How could I know it?’

‘Because I was at Cynuit, father, and Odda the Younger could have told you that I was there and that I lived.’

I was staring at Odda as I spoke and Beocca caught the grimness in my voice. ‘You were at Cynuit?’ he asked nervously.

‘Odda the Younger didn’t tell you?’

‘He said nothing.’

‘Nothing!’ I kicked my horse forward, forcing it between the kneeling men and thus closer to Odda. Beocca tried to stop me, but I pushed his hand away from my bridle. Leofric, wiser than me, held back, but I pushed the horse into the back rows of the congregation until the press of worshippers made it impossible to advance further, and then I stared at Odda as I spoke to Beocca. ‘He didn’t describe Ubba’s death?’ I asked.

‘He says Ubba died in the shield wall,’ Beocca said, his voice a hiss so that he did not disturb the liturgy, ‘and that many men contributed to his death.’

‘Is that all he told you?’

‘He says he faced Ubba himself,’ Beocca said.

‘So who do men think killed Ubba Lothbrokson?’ I asked.