По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

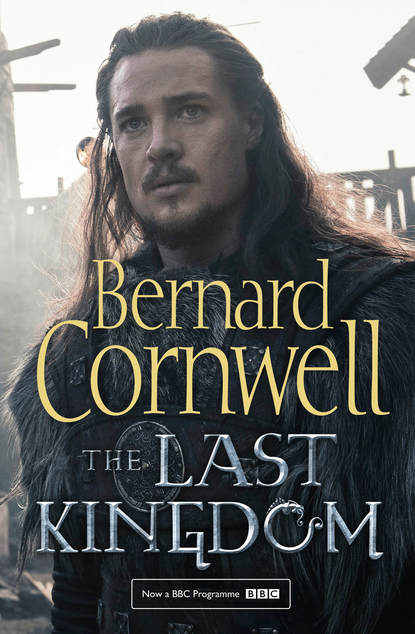

The Last Kingdom

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I want Bebbanburg,’ I said.

‘Then you must take it. Perhaps I will help you, but not yet. Before that we go south, and before we go south we must persuade Odin to look on us with favour.’

I still did not understand the Danish way of religion. They took it much less seriously than we English, but the women prayed often enough and once in a while a man would kill a good beast, dedicate it to the gods, and mount its bloody head above his door to show that there would be a feast in Thor or Odin’s honour in his house, but the feast, though it was an act of worship, was always the same as any other drunken feast.

I remember the Yule feast best because that was the week Weland came. He arrived on the coldest day of the winter when the snow was heaped in drifts, and he came on foot with a sword by his side, a bow on his shoulder and rags on his back and he knelt respectfully outside Ragnar’s house. Sigrid made him come inside and she fed him and gave him ale, but when he had eaten he insisted on going back into the snow and waiting for Ragnar who was up in the hills, hunting.

Weland was a snake-like man, that was my very first thought on seeing him. He reminded me of my uncle Ælfric, slender, sly and secretive, and I disliked him on sight and I felt a flicker of fear as I watched him prostrate himself in the snow when Ragnar returned.

‘My name is Weland,’ he said, ‘and I am in need of a lord.’

‘You are not a youth,’ Ragnar said, ‘so why do you not have a lord?’

‘He died, lord, when his ship sank.’

‘Who was he?’

‘Snorri, lord.’

‘Which Snorri?’

‘Son of Eric, son of Grimm, from Birka.’

‘And you did not drown?’ Ragnar asked as he dismounted and gave me the reins of his horse.

‘I was ashore, lord, I was sick.’

‘Your family? Your home?’

‘I am son of Godfred, lord, from Haithabu.’

‘Haithabu!’ Ragnar said sourly. ‘A trader?’

‘I am a warrior, lord.’

‘So why come to me?’

Weland shrugged. ‘Men say you are a good lord, a ring-giver, but if you turn me down, lord, I shall try other men.’

‘And you can use that sword, Weland Godfredson?’

‘As a woman can use her tongue, lord.’

‘You’re that good, eh?’ Ragnar asked, as ever unable to resist a jest. He gave Weland permission to stay, sending him to Synningthwait to find shelter, and afterwards, when I said I did not like Weland, Ragnar just shrugged and said the stranger needed kindness. We were sitting in the house, half choking from the smoke that writhed about the rafters. ‘There is nothing worse, Uhtred,’ Ragnar said, ‘than for a man to have no lord. No ring-giver,’ he added, touching his own arm rings.

‘I don’t trust him,’ Sigrid put in from the fire where she was making bannocks on a stone. Rorik, recovering from his sickness, was helping her, while Thyra, as ever, was spinning. ‘I think he’s an outlaw,’ Sigrid said.

‘He probably is,’ Ragnar allowed, ‘but my ship doesn’t care if its oars are pulled by outlaws.’ He reached for a bannock and had his hand slapped away by Sigrid who said the cakes were for Yule.

The Yule feast was the biggest celebration of the year, a whole week of food and ale and mead and fights and laughter and drunken men vomiting in the snow. Ragnar’s men gathered at Synningthwait and there were horse races, wrestling matches, competitions in throwing spears, axes and rocks, and, my favourite, the tug of war where two teams of men or boys tried to pull the other into a cold stream. I saw Weland watching me as I wrestled with a boy a year older than me. Weland already looked more prosperous. His rags were gone and he wore a cloak of fox fur. I got drunk that Yule for the first time, helplessly drunk so that my legs would not work and I lay moaning with a throbbing head and Ragnar roared with laughter and made me drink more mead until I threw up. Ragnar, of course, won the drinking competition, and Ravn recited a long poem about some ancient hero who killed a monster and then the monster’s mother who was even more fearsome than her son, but I was too drunk to remember much of it.

And after the Yule feast I discovered something new about the Danes and their gods, for Ragnar had ordered a great pit dug in the woods above his house, and Rorik and I helped make the pit in a clearing. We axed through tree roots, shovelled out earth, and still Ragnar wanted it deeper, and he was only satisfied when he could stand in the base of the pit and not see across its lip. A ramp led down into the hole, beside which was a great heap of excavated soil.

The next night all Ragnar’s men, but no women, walked to the pit in the darkness. We boys carried pitch-soaked torches that flamed under the trees, casting flickering shadows that melted into the surrounding darkness. The men were all dressed and armed as though they were going to war.

Blind Ravn waited at the pit, standing at the far side from the ramp, and he chanted a great epic in praise of Odin. On and on it went, the words as hard and rhythmic as a drum beat, describing how the great god had made the world from the corpse of the giant Ymir, and how he had hurled the sun and moon into the sky, and how his spear, Gungnir, was the mightiest weapon in creation, forged by dwarves in the world’s deeps, and on the poem went and the men gathered around the pit seemed to sway to the poem’s pulse, sometimes repeating a phrase, and I confess I was almost as bored as when Beocca used to drone on in his stammering Latin, and I stared out into the woods, watching the shadows, wondering what things moved in the dark and thinking of the sceadugengan.

I often thought of the sceadugengan, the Shadow-Walkers. Ealdwulf, Bebbanburg’s blacksmith, had first told me of them. He had warned me not to tell Beocca of the stories, and I never did, and Ealdwulf told me how, before Christ came to England, back when we English had worshipped Woden and the other gods, it had been well known that there were Shadow-Walkers who moved silent and half-seen across the land, mysterious creatures who could change their shapes. One moment they were wolves, then they were men, or perhaps eagles, and they were neither alive nor dead, but things from the shadow world, night-beasts, and I stared into the dark trees and I wanted there to be sceadugengan out there in the dark, something that would be my secret, something that would frighten the Danes, something to give Bebbanburg back to me, something as powerful as the magic which brought the Danes victory.

It was a child’s dream, of course. When you are young and powerless you dream of possessing mystical strength, and once you are grown and strong you condemn lesser folk to that same dream, but as a child I wanted the power of the sceadugengan. I remember my excitement that night at the notion of harnessing the power of the Shadow-Walkers before a whinny brought my attention back to the pit and I saw that the men at the ramp had divided, and that a strange procession was coming from the dark. There was a stallion, a ram, a dog, a goose, a bull and a boar, each animal led by one of Ragnar’s warriors, and at the back was an English prisoner, a man condemned for moving a field marker, and he, like the beasts, had a rope about his neck.

I knew the stallion. It was Ragnar’s finest, a great black horse called Flame-Stepper, a horse Ragnar loved. Yet Flame-Stepper, like all the other beasts, was to be given to Odin that night. Ragnar did it. Stripped to his waist, his scarred chest broad in the flamelight, he used a war axe to kill the beasts one by one, and Flame-Stepper was the last animal to die and the great horse’s eyes were white as it was forced down the ramp. It struggled, terrified by the stench of blood that had splashed the sides of the pit, and Ragnar went to the horse and there were tears on his face as he kissed Flame-Stepper’s muzzle, and then he killed him, one blow between the eyes, straight and true, so that the stallion fell, hooves thrashing, but dead within a heartbeat. The man died last, and that was not so distressing as the horse’s death, and then Ragnar stood in the mess of blood-matted fur and raised his gore-smothered axe to the sky. ‘Odin!’ he shouted.

‘Odin!’ Every man echoed the shout, and they held their swords or spears or axes towards the steaming pit. ‘Odin!’ they shouted again, and I saw Weland the snake staring at me across the firelit slaughter hole.

All the corpses were taken from the pit and hung from tree branches. Their blood had been given to the creatures beneath the earth and now their flesh was given to the gods above, and then we filled in the pit, we danced on it to stamp down the earth, and the jars of ale and skins of mead were handed around and we drank beneath the hanging corpses. Odin, the terrible god, had been summoned because Ragnar and his people were going to war.

I thought of the blades held over the pit of blood, I thought of the god stirring in his corpse-hall to send a blessing on these men, and I knew that all England would fall unless it found a magic as strong as the sorcery of these strong men. I was only ten years old, but on that night I knew what I would become.

I would join the sceadugengan, I would be a Shadow-Walker.

Two (#ulink_cb0ab8de-d121-5124-9297-f6e340b1d436)

Springtime, the year 868, I was eleven years old and the Wind-Viper was afloat.

She was afloat, but not at sea. The Wind-Viper was Ragnar’s ship, a lovely thing with a hull of oak, a carved serpent’s head at the prow, an eagle’s head at the stern and a triangular wind-vane made of bronze on which a raven was painted black. The wind-vane was mounted at her masthead, though the mast was now lowered and being supported by two timber crutches so that it ran like a rafter down the centre of the long ship. Ragnar’s men were rowing and their painted shields lined the ship’s sides. They chanted as they rowed, pounding out the tale of how mighty Thor had fished for the dread Midgard Serpent that lies coiled about the roots of the world, and how the serpent had taken the hook baited with an ox’s head, and how the giant Hymir, terrified of the vast snake, had cut the line. It is a good tale and its rhythms took us up the River Trente, which is a tributary of the Humber and flows from deep inside Mercia. We were going south, against the current, but the journey was easy, the ride placid, the sun warm and the river’s margins thick with flowers. Some men rode horses, keeping pace with us on the eastern bank, while behind us was a fleet of beast-prowed ships. This was the army of Ivar the Boneless and Ubba the Horrible, a host of Northmen, sword-Danes, going to war.

All eastern Northumbria belonged to them, western Northumbria offered grudging allegiance, and now they planned to take Mercia which was the kingdom at England’s heartland. The Mercian territory stretched south to the River Temes where the lands of Wessex began, west to the mountainous country where the Welsh tribes lived, and east to the farms and marshes of East Anglia. Mercia, though not as wealthy as Wessex, was much richer than Northumbria and the River Trente ran into the kingdom’s heart and the Wind-Viper was the tip of a Danish spear aimed at that heart.

The river was not deep, but Ragnar boasted that the Wind-Viper could float on a puddle, and that was almost true. From a distance she looked long, lean and knife-like, but when you were aboard you could see how the midships flared outwards so that she sat on the water like a shallow bowl rather than cut through it like a blade, and even with her belly laden with forty or fifty men, their weapons, shields, food and ale, she needed very little depth. Once in a while her long keel would scrape on gravel, but by keeping to the outside of the river’s sweeping bends we were able to stay in sufficient water. That was why the mast had been lowered, so that, on the outside of the river’s curves, we could slide under the overhanging trees without becoming entangled.

Rorik and I sat in the prow with his grandfather, Ravn, and our job was to tell the old man everything we could see, which was very little other than flowers, trees, reeds, waterfowl and the signs of trout rising to mayfly. Swallows had come from their winter sleep and swooped across the river while martins pecked at the banks to collect mud for their nests. Warblers were loud, pigeons clattered through new leaves and the hawks slid still and menacing across the scattered clouds. Swans watched us pass and once in a while we would see otter cubs playing beneath the pale-leaved willows and there would be a flurry of water as they fled from our coming. Sometimes we passed a riverside settlement of thatch and timber, but the folks and their livestock had already run away.

‘Mercia is frightened of us,’ Ravn said. He lifted his white, blind eyes to the oncoming air, ‘and they are right to be frightened. We are warriors.’

‘They have warriors too,’ I said.

Ravn laughed. ‘I think only one man in three is a warrior, and sometimes not even that many, but in our army, Uhtred, every man is a fighter. If you do not want to be a warrior you stay home in Denmark. You till the soil, herd sheep, fish the sea, but you do not take to the ships and become a fighter. But here in England? Every man is forced to the fight, yet only one in three or maybe only one in four has the belly for it. The rest are farmers who just want to run. We are wolves fighting sheep.’

Watch and learn, my father had said, and I was learning. What else can a boy with an unbroken voice do? One in three men are warriors, remember the Shadow-Walkers, beware the cut beneath the shield, a river can be an army’s road to a kingdom’s heart, watch and learn.

‘And they have a weak king,’ Ravn went on. ‘Burghred, he’s called, and he has no guts for a fight. He will fight, of course, because we shall force him, and he will call on his friends in Wessex to help him, but in his weak heart he knows he cannot win.’

‘How do you know?’ Rorik asked.

Ravn smiled. ‘All winter, boy, our traders have been in Mercia. Selling pelts, selling amber, buying iron ore, buying malt, and they talk and they listen and they come back and they tell us what they heard.’

Kill the traders, I thought.