По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

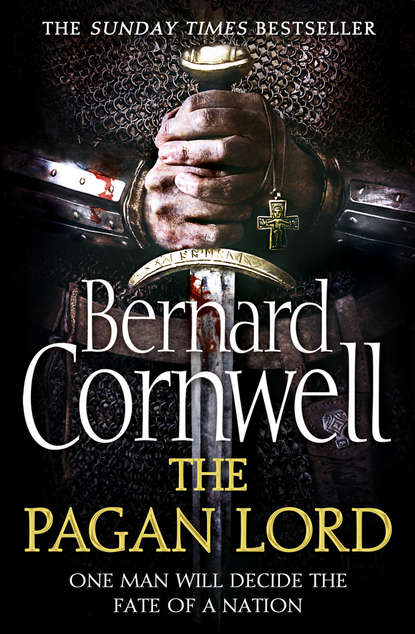

The Pagan Lord

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I kept my eyes on the crowd and touched my right hand to Serpent-Breath’s hilt. ‘You do not give me orders, Wulfheard,’ I said, not looking at him.

‘I bring you orders,’ he said grandly, ‘from Almighty God and from the Lord Æthelred.’

‘I’m sworn to neither,’ I said, ‘so their orders mean nothing.’

‘You mock God!’ the bishop shouted loud enough for the crowd to hear.

That crowd murmured and a few even edged forward as if to attack my men.

Bishop Wulfheard also edged forward. He ignored me now and called to my men instead. ‘The Lord Uhtred,’ he shouted, ‘has been declared outcast of God’s church! He has killed a saintly abbot and wounded other men of God! It has been decreed that he is banished from this land, and further decreed that any man who follows him, who swears loyalty to him, is also outcast from God and from man!’

I sat still. Lightning thumped a heavy hoof on the soft turf and the bishop’s horse shifted warily away. There was silence from my men. Some of their wives and children had seen us and they were streaming across the meadow, seeking the protection of our weapons. Their homes had been burned. I could see the smoke sifting up from the street on the small western hill.

‘If you wish to see heaven,’ the bishop called to my men, ‘if you wish your wives and children to enjoy the saving grace of our Lord Jesus, then you must leave this evil man!’ He pointed at me. ‘He is cursed of God, he is cast into an outer darkness! He is condemned! He is reprobate! He is damned! He is an abomination before the Lord! An abomination!’ He evidently liked that word, because he repeated it. ‘An abomination! And if you remain with him, if you fight for him, then you too shall be cursed, both you and your wives and your children also! You and they will be condemned to the everlasting tortures of hell! You are therefore absolved of your loyalty to him! And know that to kill him is no sin! To kill this abomination is to earn the grace of God!’

He was inciting them to my death, but not one of my men moved to attack me, though the rabble found new courage and shuffled forward, growling. They were nerving themselves to swarm at me. I glanced back at my men and saw they were in no mood to fight this crowd of enraged Christians because my men’s wives were not seeking protection, as I had thought, but trying to pull them away from me, and I remembered something Father Pyrlig had once said to me, that women were ever the most avid worshippers, and I saw that these women, all Christians, were undermining my men’s loyalties.

What is an oath? A promise to serve a lord, but to Christians there is always a higher allegiance. My gods demand no oaths, but the nailed god is more jealous than any lover. He tells his followers that they can have no other gods beside himself, and how ridiculous is that? Yet the Christians grovel to him and abandon the older gods. I saw my men waver. They glanced at me, then some spurred away, not towards the ranting mob, but westwards away from the crowd and away from me. ‘It’s your fault.’ Bishop Wulfheard had forced his horse back towards me. ‘You killed Abbot Wihtred, a holy man, and God’s people have had enough of you.’

Not all my men wavered. Some, mostly Danes, spurred towards me, as did Osferth. ‘You’re a Christian,’ I said to him, ‘why don’t you abandon me?’

‘You forget,’ he said, ‘that I was abandoned by God. I’m a bastard, already cursed.’

My son and Æthelstan had also stayed, but I feared for the younger boy. Most of my men were Christians and they had ridden away from me, while the threatening crowd was numbered in the hundreds and they were being encouraged by priests and monks. ‘The pagans must be destroyed!’ I heard a black-bearded priest shout. ‘He and his woman! They defile our land! We are cursed so long as they live!’

‘Your priests threaten a woman?’ I asked Wulfheard. Sigunn was by my side, mounted on a small grey mare. I kicked Lightning towards the bishop, who wrenched his horse away. ‘I’ll give her a sword,’ I told him, ‘and let her gut your gutless guts, you mouse-prick.’

Osferth caught up with me and took hold of Lightning’s bridle. ‘A retreat might be prudent, lord,’ he said.

I drew Serpent-Breath. It was deep dusk now, the western sky was a glowing purple shading to grey and then to a wide blackness in which the first stars glittered through tiny rents in the clouds. The light of the fires reflected from Serpent-Breath’s wide blade. ‘Maybe I’ll kill myself a bishop first,’ I snarled, and turned Lightning back towards Wulfheard, who rammed his heels so that his horse leaped away, almost unsaddling his rider.

‘Lord!’ Osferth shouted in protest and kicked his own horse forward to intercept me. The crowd thought the two of us were pursuing the bishop and they surged forward. They were screaming and shouting, brandishing their crude weapons and lost in the fervour of their God-given duty, and I knew we would be overwhelmed, but I was angry too and I thought I would rather carve a path through that rabble than be seen to run away.

And so I forgot the fleeing bishop, but instead just turned my horse towards the crowd. And that was when the horn sounded.

It blared, and from my right, from where the sun glowed beneath the western horizon, a stream of horsemen galloped to place themselves between me and the crowd. They were in mail, they carried swords or spears, and their faces were hidden by the cheek-pieces of their helmets. The flamelight glinted from those helmets, turning them into blood-touched spear-warriors whose stallions threw up gouts of damp earth as the horses slewed around so that the newcomers faced the crowd.

One man faced me. His sword was lowered as he trotted his stallion towards Lightning, then the blade flicked up in a salute. I could see he was grinning. ‘What have you done, lord?’ he asked.

‘I killed an abbot.’

‘You made a martyr and a saint then,’ he said lightly, then twisted in the saddle to look past the horsemen at the crowd, which had checked its advance but still looked threatening. ‘You’d think they’d be grateful for another saint, wouldn’t you?’ he said. ‘But they’re not happy at all.’

‘It was an accident,’ I said.

‘Accidents have a way of finding you, lord,’ he said, grinning at me. It was Finan, my friend, the Irishman who commanded my men if I was absent, and the man who had been protecting Æthelflaed.

And there she was, Æthelflaed herself, and the angry murmur of the rabble died away as she rode slowly to face them. She was mounted on a white mare, wore a white cloak, and had a circlet of silver about her pale hair. She looked like a queen, and she was the daughter of a king, and she was loved in Mercia. Bishop Wulfheard, recognising her, spurred to her side where he spoke low and urgently, but she ignored him. She ignored me too, facing the crowd and straightening in her saddle. For a while she said nothing. The flames of the burning buildings flickered reflections from the silver she wore in her hair and about her neck and on her slim wrists. I could not see her face, but I knew that face so well, and knew it would be icy stern. ‘You will leave,’ she said almost casually. A growl sounded and she repeated the command in a louder voice. ‘You will leave!’ She waited until there was silence. ‘The priests here, the monks here, will lead you away. Those of you who have come far will need shelter and food, and you will find both in Cirrenceastre. Now go!’ She turned her horse and Bishop Wulfheard turned after her. I saw him plead with her, and then she raised a hand. ‘Who commands here, bishop,’ she demanded, ‘you or I?’ There was such a challenge in those words.

Æthelflaed did not rule in Mercia. Her husband was the Lord of Mercia and, if he had possessed a pair of balls, might have called himself king of this land, but he had become the thrall of Wessex. His survival depended on the help of West Saxon warriors, and those only helped him because he had taken Æthelflaed as his wife and she was the daughter of Alfred, who had been the greatest of the West Saxon kings, and she was also the sister of Edward, who now ruled in Wessex. Æthelred hated his wife, yet needed her, and he hated me because he knew I was her lover, and Bishop Wulfheard knew it too. He had stiffened at her challenge, then glanced towards me, and I knew he was half tempted to meet her challenge and try to reimpose his mastery over the vengeful crowd, but Æthelflaed had calmed them. She did rule here. She ruled because she was loved in Mercia, and the folk who had burned my steading did not want to offend her. The bishop did not care. ‘The Lord Uhtred,’ he began and was summarily interrupted.

‘The Lord Uhtred,’ Æthelflaed spoke loudly so that as many folk as possible could hear her, ‘is a fool. He has offended God and man. He is declared outcast! But there will be no bloodshed here! Enough blood has been spilled and there will be no more. Now go!’ Those last two words were addressed to the bishop, but she glanced at the crowd and gestured that they should leave too.

And they went. The presence of Æthelflaed’s warriors was persuasive, of course, but it had been her confidence and authority that overrode the rabid priests and monks who had encouraged the crowd to destroy my estate. They drifted away, leaving the flames to light the night. Only my men remained, and those men who were sworn to Æthelflaed, and she turned towards me at last and stared at me with anger. ‘You fool,’ she said.

I said nothing. I was sitting in the saddle, gazing at the fires, my mind as bleak as the northern moors. I suddenly thought of Bebbanburg, caught between the wild northern sea and the high bare hills.

‘Abbot Wihtred was a good man,’ Æthelflaed said, ‘a man who looked after the poor, who fed the hungry and clothed the naked.’

‘He attacked me,’ I said.

‘And you are a warrior! The great Uhtred! And he was a monk!’ She made the sign of the cross. ‘He came from Northumbria, from your country, where the Danes persecuted him, but he kept the faith! He stayed true despite all the scorn and hatred of the pagans, only to die at your hands!’

‘I didn’t mean to kill him,’ I said.

‘But you did! And why? Because your son becomes a priest?’

‘He is not my son.’

‘You big fool! He is your son and you should be proud of him.’

‘He is not my son,’ I said stubbornly.

‘And now he’s the son of nothing,’ she spat. ‘You’ve always had enemies in Mercia, and now they’ve won. Look at it!’ She gestured angrily at the burning buildings. ‘Æthelred will send men to capture you, and the Christians want you dead.’

‘Your husband won’t dare attack me,’ I said.

‘Oh he’ll dare! He has a new woman. She wants me dead, and you dead too. She wants to be Queen of Mercia.’

I grunted, but stayed silent. Æthelflaed spoke the truth, of course. Her husband, who hated her and hated me, had found a lover called Eadith, a thegn’s daughter from southern Mercia, and rumour said she was as ambitious as she was beautiful. She had a brother named Eardwulf who had become the commander of Æthelred’s household warriors, and Eardwulf was as capable as his sister was ambitious. A band of hungry Welshmen had ravaged the western frontier and Eardwulf had hunted them, trapped them, and destroyed them. A clever man, I had heard, thirty years younger than me, and brother to an ambitious woman who wanted to be a queen.

‘The Christians have won,’ Æthelflaed told me.

‘You’re a Christian.’

She ignored that. Instead she just gazed blankly at the fires, then shook her head wearily. ‘We’ve had peace these last years.’

‘That’s not my fault,’ I said angrily. ‘I asked for men again and again. We should have captured Ceaster and killed Haesten and driven Cnut out of northern Mercia. It isn’t peace! There won’t be peace till the Danes are gone.’

‘But we do have peace,’ she insisted, ‘and the Christians don’t need you when there’s peace. If there’s war then all they want is Uhtred of Bebbanburg fighting for them, but now? Now we’re at peace? They don’t need you now, and they’ve always wanted to be rid of you. So what do you do? You slaughter one of the holiest men in Mercia!’

‘Holy?’ I sneered. ‘He was a stupid man who picked a fight.’

‘And the fight he picked was your fight!’ she said forcibly. ‘Abbot Wihtred was the man preaching about Saint Oswald! Wihtred had the vision! And you killed him!’

I said nothing to that. There was a holy madness adrift in Saxon Britain, a belief that if Saint Oswald’s body could be discovered then the Saxons would be reunited, meaning that those Saxons under Danish rule would suddenly become free. Northumbria, East Anglia and northern Mercia would be purged of Danish pagans, and all because a dismembered saint who had died almost three hundred years in the past would have his various body parts stitched together. I knew all about Saint Oswald: he had once ruled in Bebbanburg, and my uncle, the treacherous Ælfric, possessed one of the dead man’s arms. I had escorted the saint’s head to safety years before, and the rest of him was supposed to be buried at a monastery somewhere in southern Northumbria.

‘Wihtred wanted what you want,’ Æthelflaed said angrily, ‘he wanted a Saxon ruler in Northumbria!’