По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

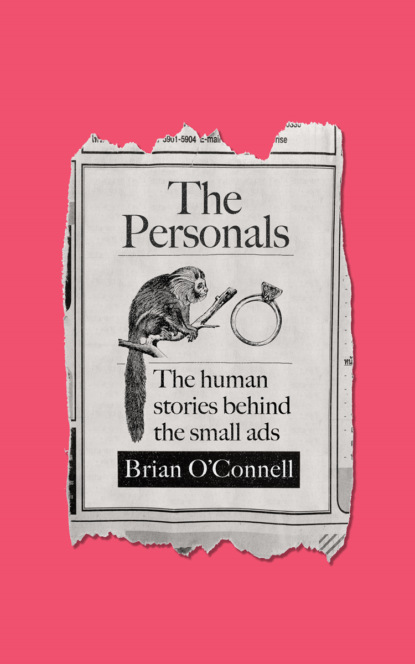

The Personals

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

By collating a selection of recent adverts and some I have captured over the last few years, I want to take you down lanes and into homes, into hearts and cluttered minds and tell stories that would not otherwise be told. In all except maybe half a dozen of these stories, I have met the people behind the ads in person, usually travelling to their homes or meeting them in a car or cafe nearby. When that wasn’t possible, or the poster did not want to meet, we spoke at length on the phone or through email.

What draws me into these ads are the personal stories – the reasons for a break-up, how a child collector became an adult one or why someone feels the need to sell a treasured ring that has come to represent something tainted or tragic.

Through the years there have been some important ads that have signalled significant societal change. These were the ads in the early part of the twentieth century looking for ‘good Catholic homes’ for the children of ‘fallen women’ for example, or the aged bachelor farmers looking for girls in their late teens to become ‘life partners’, or those looking for domestic servants, or the emigrants in Australia trying to reconnect with family many decades later. You could write a whole social history on the classified ads of past decades.

Two books worth reading on this are Strange Red Cow, Sarah Bader’s fascinating trawl through the vintage classified ads of US publications, and Classified by H. G. Cocks, an interesting take on how sexuality and society evolved in Britain, again through the prism of the small ads. In his book, Cocks traces the rise of personal ads to respectability, from one of the first ecclesiastical style ads in the fifteenth century through the invention of modern newspapers in the mid-seventeenth century right up to today. One of his central points is that the internet today ‘merely accelerates processes which, when people had to rely on print and the postal service, just took longer to achieve.’ Cocks makes a compelling argument that the small ad was a ‘symbol of everything that was both exciting and dangerous about modern sexuality’ and that the classifieds have been a gateway to all sorts of delights and dangers ever since their invention, showing how ordinary people grappled with love, sex, marriage, friendship and commerce through recent centuries.

All the stories in this book are quite recent and attempt to document snapshots of life in Ireland today. There are also stories and ads which I hope bring history to life – such as the military medals and memorabilia for sale, the nineteenth-century hearse, the impact of mother and baby homes or the frayed match programme for a long forgotten All-Ireland final.

I’ve divided the book into parts and the timeline roughly spans the period from 2012 to the present. In several of the stories, you’ll notice that I haven’t given the name of the person posting the ad and don’t identify where they’re located, or I’ve used a pseudonym. This is at their request and I was happy to proceed on the basis that no one was identified, especially with some of the more sensitive ads. I don’t think this detracts from the account of their experiences.

The way I sourced the material was simple. Most weeks I scoured the small ads in places such as the Evening Echo (since renamed The Echo) or online on DoneDeal. I was looking for hints that there was a story or a life experience worth hearing hidden behind the few lines of text on page or screen.

When I thought an ad had potential I would text the poster, explain that I was interested in the story behind it and ask whether they would take a call. Some thought I was part of an elaborate scam to fiddle them out of their item for sale, while others, particularly those recently bereaved, were very happy to sit and talk about their life experiences.

I’m very grateful to everyone who shared their stories and let me into their homes, or met me in hotels, cafes or parked cars, or took a phone call and spilled their heart out and shared with me intimate details of their life. There was really nothing in it for them; by the time this book is published most of their ads will have long since expired, so it was hugely refreshing to be able to talk to people simply because they wanted to share some of their story with me.

While the ad is a signpost, it’s ultimately the people who drew me in, and the adage that everyone has a story. The privilege for me is in contacting a stranger and shortly afterwards sharing some of the more intimate moments of their life, with no agenda or preconditions. Throughout this process the joy was in finding unexpected twists and turns, lessons learned and the life experiences gained, all trapped iceberg-like beneath a few lines of classified text on a page or screen. Those kinds of discoveries are what brought me back again and again to these stories.

Some people do Sudoku, others binge on box sets; I trawl the classified ads ...

Part One

LOVE AND LOSS (#u02bac65b-4738-563e-9594-7c57dd2d8310)

When East Meets West (#u02bac65b-4738-563e-9594-7c57dd2d8310)

Beautiful wedding and engagement ring for sale. €3,000 or nearest offer. DoneDeal, June 2018

Weeds are growing up through the barriers at the edge of the estate I’m driving through, as Google Maps and I have one of our many disagreements and I circle round at least half a dozen times.

The gravel-filled fields beyond those barriers were once called ‘Phase 2’ on a glossy Celtic Tiger era brochure, probably launched in a penthouse with a rugby player and canapés. Now the scabby site adjacent remains a stubborn scar on the landscape, a reminder that we lost control and that this estate was over-hyped and over-extended until the building came to an abrupt end.

I’m in one of the attractive, three-bedroomed, semi-detached houses which could easily have been the show house. Large candles are lit around the fireplace and there’s one of those evocative black and white coastal prints on the wall. Despite the welcome, it has been made clear to me that I will have to grant anonymity to the seller, because the events which led to the rings being put up for sale were relatively recent and raw. Apart from that precondition, she really wanted to tell her story and had seemed warm and friendly on the phone.

She is a fortysomething woman, and in her sitting room there are clues that she is well travelled – an African mask here, an Asian figurine there. I’m not sure that it’s a house that has seen many four a.m. Christy Moore singalongs; everything seems particularly placed, and because we meet just as she’s come in from work, I assume that the house always looks this gleaming and wasn’t scrubbed for my sake. I also guess that no small children live here – the lighted candles and open bowls of potpourri give this away.

We take a seat on the couch and I can see she’s a little nervous, but also quite open, and in her hand, she flips the lid of a ring box open and closed while we make small talk and I compliment her on the interior. I watch as each flick open reveals glistening stones, while each movement shut smothers the sparkly diamonds in darkness. She tells me that her rings have been in this box since last year and pauses, presumably waiting for me to ask what happened. I hold off as I often do in these encounters. Sometimes the longer you hold off talking about the elephant in the room the louder the elephant will demand to be heard. Also, we’re having tea and the biscuits are really nice.

By way of easing into the story, I ask her to describe the rings to me, which saves me the embarrassment of discussing something I know zilch about. ‘The engagement ring is a solitaire ring and it has encrusted diamonds halfway on each shoulder,’ she explains, thinking about, and then resisting the urge, to put it on her finger. ‘The wedding ring would have the same type of encrusted diamonds. So, this is a band of diamonds and they have the same set on the side. They are stunning rings. I think in total it’s one carat. I initially picked the diamonds and I got them in Dubai and the company that were making them for me called me up to say they had sourced a nicer-quality diamond, and they were looking for permission to put it in. So, it was crafted with great care and consideration and there’s no inscription on them.’

The rings, the box, the inlay cards and the lack of inscription all make it look as if they’ve just come off the shelf from a high-street jeweller. Have they ever actually been on her finger, I ask? ‘Yes, they went on my finger in December 2015 and they came off in September 2017. So just under two years. Do you want to know the story?’

As we continued to chat over tea and Club Milks, it became clear that while parts of this story were about lost love (or perhaps false love), another part was about the pressure to conform. More accurately, it’s about the social anxiety that builds when you get to your late thirties, see your friends marry and partner up one by one, and feel that part of society has its sights fixed on you and that some judge you by your singleness. In reality of course, those who have partnered up and are dealing with early morning Peppa Pig breakfasts are probably so preoccupied with lack of sleep and reducing their mortgage repayments that they barely notice anything except their expanding midriffs and greying hairs.

That insight into single life will come later; for now I ask my host if she would like to tell me how she fell in love. ‘Well, I married a non-EU national, someone from the Middle East, in Lebanon in December 2015,’ she explains, in a voice that’s not so much bitter as rueful. ‘We had known each other a year and a half at that stage. What attracted me to him was his drive and his commitment to working with young people. I share the same values. He proposed to me and of course I said yes to this handsome man.’

And for the first time the nerves are gone and she’s smiling as she recounts their early courtship. Had she any hesitation at the time, I ask? ‘In my naivety, no,’ she says. ‘I had considered motivations briefly; why he would ask someone to marry so quickly, but I would have thought maybe he loved me. I didn’t really question that. I should have.’

After they married, she returned home in late 2015, and after Christmas that year applied for his spousal visa so he could come to Ireland. This application turned into a lengthy and intrusive process during which their relationship needed to be verified, requiring testimony from family and friends that it was a legitimate marriage.

All her family were happy to give their testimony, and all were convinced this relationship was for real. In total, the process cost €4,000. This should have been the starting point for a wonderful life together in Ireland. Instead, it became the point at which their short marriage came unstuck and she felt the gaze of partnered society even more acutely. ‘His visa was refused in August 2017,’ she says. ‘And the day after I told him it had been refused, he told me he was marrying someone else. Just like that.’

Her voice fills with emotion as she tells me this, as when someone recalls a recent bereavement. Two weeks after that phone call she was devastated when it was confirmed that her husband had in fact married someone else. While their relationship had been long distance, he had been to Ireland for a visit, and she had been to his country several times, and they spoke on the phone every day. But a fortnight after she had told him of the visa refusal, her husband’s new wife sent her a screenshot of their marriage certificate. Talk about moving on quickly ...

It’s a difficult question, but I ask her whether she thinks his second marriage was prompted by the visa refusal. After a long pause, she looks at me with reddening eyes and says: ‘Yeah. I think it was just a matter of what will he do next to make life comfortable for himself? I think he was able to draw a line under it very quickly and move on to his next plan. He denied it for a while. His family confirmed he had got married again, and for a while I was bargaining with him, saying, “It is OK; you can remain married to her and remain married to me as well,” – he can have four wives after all, because of his culture.’

Our conversation was taking place 11 months after the break-up and while the wound is still not fully healed, she has moved on significantly. She shakes her head when she tells me about her attempts to bargain with him, and how she considered allowing her husband to have another wife in another country. She recognises this as a sign of her desperation to keep him and their marriage, whatever the cost. It’s totally understandable, I tell her – she’d told all her friends and family, had the big day, made life plans with someone and then, bang, it was all pulled from under her.

‘It was an enormous shock. I was definitely not able to eat for about three weeks,’ she says. ‘I couldn’t even talk about it, to be honest. There was a lot of shame because I should have known better. You read these things in magazines and you see these things on TV shows. And you are saying to yourself, that would never happen to me, how stupid could that person be? But, it’s not until you experience it and are drawn and pulled into it, in what appears to be a meaningful relationship. And then you have utter shame around falling for it. But it happens …’

‘Yes, it happens,’ I say reassuringly. Her vulnerability is clear, and while I can see she has thought long and hard about this whole episode, and has probably spent many nights looking at those log-sized candles flickering and filling the empty space on the couch beside her, the grief has not gone away; she has just learned to adapt to it most of the time.

What’s keeping her anchored to the sailed ship that was her marriage is the fact that she cannot legally divorce her husband, despite the fact that he is living with another woman in another country. ‘I’m not able to divorce him from here,’ she affirms. ‘I don’t want to go over there and get divorced. But I have made enquiries and the only choice I have is to hire a solicitor in his country to do the divorce or else go back to the mosque so he would have to grant it. I was advised not to go ...’

So, while she figures out how to remove herself from the marriage, she is faced with legal bills for the failed visa application, not to mention the costs associated with the wedding, most of which she has borne. The engagement and wedding rings were bought in Dubai. In total they cost €5,000, the majority of which she paid herself. She will sell them for €3,000. ‘They are stunning rings,’ she adds. ‘When they were on my hand, everyone would stop and pick them up and look at the weight of them and remark how stunning they were. You won’t get them on anyone else in Ireland.’

There’s obviously both an emotional and financial catharsis in getting rid of the rings as quickly as she can now. Anyone who has ever been in a failed relationship will tell you it has an impact long after the last tears have been shed. But in a situation like this, when there was no advance warning, and when one party feels they were duped into love, that impact is all the more magnified. ‘I am getting there now but immediately afterwards you do question what men say. You analyse them more now and I guess I’ve to be very careful I don’t bring this into a new relationship,’ she says candidly.

I tell her that her openness and insight and her inherent humanity (which she says is often interpreted as naivety) should not have to become a casualty of this. These are the things I tell her that will paradoxically give her the best chance of falling in love again. There is something likeable about my interviewee. She has warmth and oozes care, compassion and decency. I imagine she is the kind of person who sees a news bulletin about famine in Yemen or drought in Kenya and hits the donate button there and then. But I wonder how much the failed marriage has changed her; how much it has made her less receptive to love. ‘I would be more self-aware now,’ she says. ‘I know I was a little bit naive. But I would prefer this way than to be cynical. I would prefer to be able to fall in love than to always query and question. I think that’s a lonely life. I won’t be too cynical about it. I mean, there wasn’t ever a question of whether I loved him or not.’

Before I leave she carefully puts the rings back in their boxes, and as she’s doing so, I ask what is the biggest lesson she’s learned from the whole experience. ‘I think that it can happen anyone and I think, well, you can beat yourself up about it but I think you can in the future say to yourself, you need to step back from a situation and try to look at it from different perspectives. Some of my friends would have said, you know, are you sure about this? Without overtly coming out and saying I was being duped. I said, of course I’m sure; he loves me, he tells me it. Those same friends have never come back and said we told you so. If you’re hurt to that extent, then you have to reflect on what you have done, what would I have done differently – am I that vulnerable, naive and gullible? You ask yourself all those questions. You question yourself if a man says to you, “You look lovely.” I hate that it has changed me that way, but it’s to be expected, I suppose.’

Does she ever wear the rings now? ‘No. Not any more. They’re not mine now. I hope they go on someone’s finger that will have many years of happy marriage.’

We finish our tea. I tell her that I hope she’s talking to people about how she feels, and she says she has some very close friends and they share. She’s determined not to allow the whole experience to inhibit her or in any way reduce her chances of finding ‘the one’.

Somehow, I think she’s going to be OK and I leave thinking that selling the rings is the manifestation of a need to start again, of choosing deliberately to put what were once symbols of the future firmly into the past.

A Ringless Marriage (#litres_trial_promo)

Vintage wedding and engagement ring for sale; €2,000 or nearest offer. Comes with valuation. DoneDeal, July 2018

I’m early and have parked outside a house in the west of Ireland. I’m sitting in my car waiting for the owner of the above rings to arrive home. Someone is knocking on my car window and wants to lead me into the house. As I follow, a large Alsatian appears and eyes me from inside the open front door. Just then a Land Rover pulls into the drive and a woman gets out, brushes past me and quickly closes the door before the Alsatian bolts. ‘Sorry about that,’ she says, before adding casually, ‘That dog bites.’ She half chides the man who let the dog out, before asking if I want tea or coffee and clearing a space at the kitchen table for us to sit.

I notice that the man is quite self-conscious and I also notice that she’s overseeing his tea making, or at least subtly checking each step while trying not to make it obvious that she is doing so. The kitchen is cluttered – managed clutter, I’d call it – and even though the house is on a main road in a village, outside are a collection of sheds and outbuildings, bales of hay and fields. I’m guessing that they grew up on farms, and this is their way of keeping one foot in the fields, living on the side of a busy road, yet constructing a mini farmyard out back.

There’s a nervousness in the room and some tension. I don’t sense that it’s caused by me or my microphone. I think it’s more the fact that their space is now shared with someone else and they’re very conscious of that. As cups of coffee are served the man gets closer to me without saying anything, as if he is afraid to say the wrong thing. And then I notice the box on the windowsill behind the sink. Every day of the month has a little window and some are open, advent calendar like, while others are unopened. Inside are red and white pills, and the day and date is printed on each little portal.

Something clicks, and I’m taken back to an interview I’d done years earlier beside a mountain in Tipperary, with a man and his mother, who was in the final stages of dementia. She kept pleading with me to take her away because she believed he was poisoning her. He wasn’t, of course. In reality he was keeping her alive, and had sacrificed much of his own life to ensure his mother could stay in her own home as long as possible. Her illness meant that she took her anger and frustration out on him every day. She kept saying to me over and over, pointing to imaginary marks on her body: ‘Look what he did to me ... look.’ And there they lived, together and alone at the foot of a mountain; mother and adult son entwined in their love and false hate, their reality and their fiction. Long after I’d driven away from the house they were still with me. They are in my mind now in this half farmhouse, where two adults are reframing their relationship, forgotten fragment by forgotten fragment.

The man’s wife tells me that his dementia and diagnosis of Alzheimer’s has been a relatively recent discovery, or more accurately, that she didn’t know her husband had been diagnosed until recently. ‘I felt there was something going on,’ she says. ‘He was short-tempered and not totally focused on certain chores we would share. He wouldn’t do them, or he would forget where the keys were. Those things didn’t come in one day – it was over a period of a week. The biggest thing that made me go to the doctor with him was the fact that he wasn’t concerned about how he was dressed. He would forget things. More and more he would forget where keys were or that he put milk in the fridge without using it; silly little things really.’

Throughout these changes her husband didn’t seem particularly bothered, she says. When he got frustrated, he would lose his temper a little and it could be over the smallest of things. For example, if she asked him if he’d put the kettle on and make coffee, he might get a little hot-tempered and react by saying he was always doing it. She believes now that he has had dementia since 2016, and that Alzheimer’s developed after that. He is aware that he has Alzheimer’s, but doesn’t accept that the change in his life is due to the condition. There should be a lot more help and support for families like theirs, she says, and sometimes she feels alone and abandoned by state services. There are practical things that need to be done, such as signing the house over to their children, which he is reluctant to do.

‘He is changing into someone else,’ she says. ‘I could put my arms around him today and say, “I love you”. I could whisper in his ear that we had a great life and sometimes his response will be more measured. He might agree and say, “Remind me again how many years we are together?” But I could do the same thing later in the day, especially in bed, and he will push me away and say, “Stop that now, I have to sleep.” It’s hard to know how he will react sometimes.’

She says he can be very curt and sharp with her, and often if she is upset or crying he won’t stop what he’s doing to ask how she is and will simply walk by, oblivious to her feelings. She tries to continue to treat him as normally as she can, especially in front of other people. It would hurt him if she treated him any differently. Increasingly, she has been taking him with her when she has to leave the house. This is partly because it’s good for him to get out and about and not isolate himself, but also, at least when he is with her she knows he is safe and won’t wander down the road or leave the door open.