По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

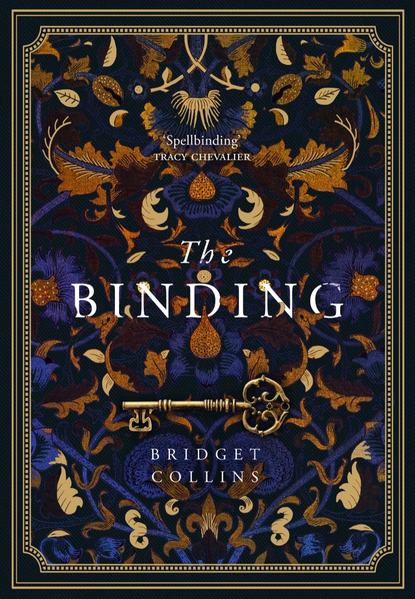

The Binding

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

One morning he passed me at the foot of the stairs as I carried a basket of logs in for the range. ‘Seredith is asleep. I’ll have a fire in the parlour.’

I clenched my jaw and dumped the wood in the kitchen without answering. I wanted to tell him to build his own fire – or something more obscene – but the thought of Seredith helpless upstairs made me swallow the words. De Havilland was a guest, whether I liked it or not; so I piled a couple of logs against my chest and carried them across the hall to the parlour. The door was open. De Havilland had turned the writing desk around and was sitting with his back to the window. He didn’t look up when I came in, only pointed to the hearth as if I wouldn’t know where it was.

I crouched and began to brush the remnants of the last fire out of the grate. The fine wood ash rose like the ghost of smoke. As I started to lay kindling I felt that creeping sensation at the base of my skull; it felt like a defeat to glance round to see if he was looking, but I couldn’t stop myself. De Havilland leant back in his chair and tapped his pen against his teeth. He regarded me for what felt like a long time, while the blood began to hum in my temples. Then he smiled faintly and turned his attention back to the letter he was writing.

I forced myself to finish the fire. I lit it and waited until the flames had taken hold. Once it was burning well I stood up and tried to brush the grey smears off my shirt.

De Havilland was reading a book. He was still holding his pen, but it lay slackly between his knuckles while he turned the pages. His face was very calm; he might have been looking out of a window. After a moment he paused, turned back a page, and made a note. When he’d finished he caught sight of me. He put down his pen and smoothed his moustache, his eyes fixed on mine above the stroking hand that covered his mouth. Abruptly his vague, interested expression gave way to a gleam of something else, and he held out the book.

‘Master Edward Albion,’ he said. ‘Bound by an anonymous binder from Albion’s own bindery. Black morocco, gold tooling, false raised bands. Headbands sewn in black and gold, endpapers marbled in red nonpareil. Would you care to have a look?’

‘I—’

‘Take it. Carefully,’ he added, with a sudden sharp edge in his voice. ‘It’s worth … oh, fifty guineas? Certainly more than you could ever repay.’

I started to reach out, but something jarred in my head and I pulled back. It was the image of his face, utterly serene, as he read: words he had no right to, someone else’s memories …

‘No? Very well.’ He put it on the table. Then he looked back at me, as if something had occurred to him, and he shook his head. ‘I see you share Seredith’s prejudices. It’s a school binding, you know. Trade, but perfectly legitimate. Nothing to offend anyone’s sensibilities.’

‘You mean—’ I stopped. I didn’t want to give him the satisfaction of asking what he meant, but he narrowed his eyes as if I had.

‘It’s unfortunate that you’ve been learning from Seredith,’ he said. ‘You must be under the impression that binding is stuck in the Dark Ages. It’s not all occult muttering and the Hwicce Book, you know – oh.’ He rolled his eyes. ‘You’ve never heard of the Hwicce Book. Or the library at Pompeii? Or the great deathbed bindings of the Renaissance, or the Fangorn bindery, or Madame Sourly … No? The North Berwick Trials? The Crusades, presumably even you know about the Crusades?’

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: