По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

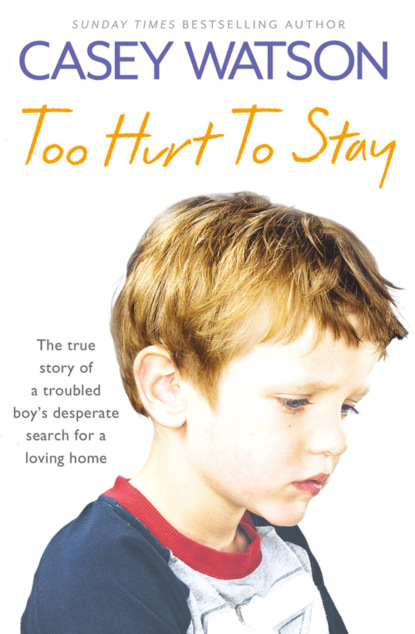

Too Hurt to Stay: The True Story of a Troubled Boy’s Desperate Search for a Loving Home

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Acknowledgements

Casey Watson (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 1 (#uc607c84b-48cb-547b-851d-0adaddac6dea)

They always say a change is as good as a rest, don’t they? And let’s face it, who wants to put their feet up and do nothing all day long? Not me.

Which was just as well. It was mid-August, a time of year where rest tends to be high on the agenda, but as I hefted my number one grandson from his car seat, my principal thought was ‘fat chance’.

I didn’t like to admit it, because at forty-three I was young for a granny, but four hours in town with my daughter Riley and her two little ones had exhausted me. Not that I hadn’t asked for it. I’d been itching to spend more time with Levi and Jackson, so I had no business moaning and groaning about it. And besides, I well remembered how tiring it was being a young mum with two little ones to run around after; with Levi almost three now and Jackson just six months old, Riley had her work cut out.

And I remembered how tiring childcare could be better than most grannies, maybe. We’d just said goodbye to our last foster children, and though at ten and seven Ashton and Olivia hadn’t exactly been toddlers, they had certainly been as challenging as little ones. As with all the kids we took, these had been profoundly damaged children, so caring for them had definitely taken its toll.

‘God, I could kill for a coffee,’ I told Riley as we got the kids indoors and settled them in the living room with some toys.

‘You sit down,’ she said. ‘I’ll deal with the drinks.’ But almost as soon as I’d lowered myself and the baby into an armchair with a picture book, the phone rang. Levi shot to his feet.

Which meant I had to be quick. He was three now and his most favourite thing at the moment was to chat on the phone. Needless to say, he beat me to it.

‘Hiya!’ he was babbling into the receiver. ‘Hiya! Lub you!’ Then his usual follow-up. ‘Okay, then. Byeee!’

I gently prised the receiver from him, despite his indignant protests, and hoped whoever was on the end hadn’t already hung up. Happily he hadn’t – it was John Fulshaw, our fostering-agency link worker – though he’d been about to. ‘Thought I’d dialled a wrong number,’ he chuckled. ‘Either that or you were doing a bit of moonlighting. Thought you’d wanted a break!’

‘It’s Levi,’ I told him. ‘And this is my break. Anyway, to what do I owe the pleasure?’

‘My, he’s growing up fast,’ John said. Then he cleared his throat. It was a sign I knew of old. A sign that invariably meant that the tone of the conversation was about to change.

‘So?’ I asked.

‘So, talking of breaks,’ he continued, ‘we…ll, I just wondered how adamant you felt on that front?’

‘Go on,’ I said slowly, while pulling a face at Riley. She was standing in the kitchen doorway, listening.

‘Well,’ John said again, obviously limbering up still, ‘we just wondered what the chances were of you taking on another placement. It’s not going to be long term …’

‘Yeah, right. Heard that one before, John.’

‘No, this time I’m sure of it. The plan here is for the child to be returned home to his family as soon as possible.’

Which seemed odd. My husband Mike and I didn’t do mainstream fostering. We were specialist carers, trained to deliver a behaviour-modification programme that was geared to helping the most profoundly damaged kids. These were kids that were too challenging to be fostered in the mainstream, and for whom the alternative was often the grim option of a secure unit. They’d often been through the system – children’s homes and foster homes – already. We were very much the ‘last-chance saloon’ for these unfortunates, our aim being to give them lots of love and firm boundaries, and in so doing improve their behaviour enough for them to be returned, not to their families – that option was mostly long gone – but to mainstream foster carers. That was what had just happened with Ashton and Olivia. So this situation was odd.

‘That sounds unusual,’ I told John.

‘Even more than you know, Casey. This kid – whose name is Spencer, by the way – is only eight, yet he took himself off to social services on his own – just marched into their offices and demanded that they put him into care.’

‘What?’ I said, laughing incredulously. ‘So he goes in there, asks for a foster carer and that’s it? Is that what you’re saying?’

‘Well, not exactly. This actually happened a few weeks ago. And was taken seriously, too. There was a suspicious-looking bruise on his wrist, which he wasn’t really able to account for – and neither was the father. Seems there’s some sort of question mark in that regard about the mum. Anyway, naturally, it’s all been followed up. Social services, family support and so on. They’ve been trying to support the family, offering coping strategies and advice, but none of it appears to have worked so far. There are five children in the family, little Spencer being the third of them, and there don’t seem to be any issues or problems with the others. Mum’s being treated for depression, apparently, but, bar this one child, the family are coping. Just not with Spencer. So that’s where we are now.’

‘Can’t cope with him? Why ever not? You say he’s eight, yes?’

‘That’s right.’

‘So what could an eight-year-old have possibly done that’s so bad?’

‘Not that much, from what I can see, except that they’ve described him as almost feral. Had a yearning for the streets from a very young age. Running away all the time, even spending whole nights missing, and the parents say they simply don’t know what to do with him any more. So now it’s turned on its head, really. It’s them who are pressing, because they don’t feel confident they can keep him safe any more.’

‘Bloody hell, John. That sounds crazy. That young and they can’t keep control of him?’

‘That’s the story. And from what social services tell me, that really is the case. The other kids all appear absolutely fine.’

‘So has he got mental-health problems? Psychological problems? What?’

‘I’m told not. The parents apparently told social services that they are at a loss themselves. They described him as vicious and abnormal, and claim he was born evil.’

I balked at that. Honestly! Some people. Children weren’t born evil. I truly believed that. They got damaged by environment, circumstances, neglect. It was that which caused behaviour to spiral out of control. Not some ‘evil’ gene. I’d yet to meet a child who was ‘born bad’. I suspected I never would, either.

‘Okay,’ I said. ‘And just when did you have in mind for this “evil” child to come to us?’

‘Well, obviously, you’ll want to speak to Mike first,’ John answered. ‘But if you’re both in agreement, we could bring him over to meet you next Monday, with a view to him moving in that same week.’

Ah, I thought. Mike. Then I tried not to think it, as the last words my husband had said to me that morning were how much he was looking forward to a few weeks of peace. Just the two of us. A proper recharge of our batteries, after what by anyone’s yardstick had been a rollercoaster of a year. ‘And tonight,’ he’d said, ‘don’t do a thing about dinner. I’m ordering in a takeaway, a nice bottle of your favourite wine, a few candles …’

Oh dear, I thought. Oh dear.

John went on to explain that Spencer was currently staying with another specialist carer temporarily. Her name was Annie and I knew her vaguely. She was in her mid-fifties, and I seemed to remember hearing on the grapevine that she’d recently lost her husband, poor thing. Because of this, and the fact that she was considering retirement soon anyway, she had asked to be considered only as a respite carer now; just stepping in when full-time foster carers needed a few days’ break. Which was why, John finished, it was important they move Spencer on quickly. I could almost hear him crossing his fingers.

‘Hmm,’ said Riley once I’d put down the phone, having promised John I’d get back to him the following morning. ‘I wouldn’t like to be in your shoes when Dad gets home, for sure. What happened to the plan to take the rest of the summer off? Flown out of the window now, has it?’

I bustled us both back into the kitchen and winked at her as I took my coffee. ‘Oh, you know me,’ I said. ‘Dad can always be persuaded …’

‘Well, rather you than me,’ she said. ‘And Dad’s right, Mum. With a job like this I think you should have a bit of a break before the next shock –’

‘Shock? Honestly, Riley you make it sound so dramatic. They’re only kids, you know, not little savages!’

Riley didn’t need to answer, because even as I said it I was reminded that when Ashton and Olivia had arrived with us, little savages were exactly what they looked like. Literally. More as if they’d strolled out of a prehistoric cave – all rags and lice and scabies – than from a council house an hour and a half’s drive away.

But if I spent the rest of the day optimistically planning my strategy to break the news to him gently, I was soon to be reminded that it was going to be a tough one. It had been a glorious afternoon, most of which we’d spent out in the garden, and when David, Riley’s partner, arrived to pick the family up, almost the first words she said to him were, ‘You’ll never guess what. Big, big news! Mum’s only agreed to take on a new kid, like, next week. And without asking Dad.’

As with Riley’s earlier, David’s expression said it all. ‘No, I haven’t!’ I protested. ‘I haven’t agreed to anything.’

Riley grinned and touched a finger to her temple. ‘Yeah, you have,’ she said, laughing. ‘So good luck.’

Back inside and tidying the toys away, I smiled to myself. Riley knew me too well. Knew how much I’d want to do this. It was exactly the sort of challenge I loved. Just eight years old and already branded so horribly. It almost beggared belief, and I wanted to know more. I tidied the toys away, washed up the few plates and cups we’d used, then swept the floor and wiped down all the kitchen surfaces. I loved to clean. So much so that in my past life I think I must have been a scullery maid, but even with my exacting standards of housewifery the fact was that it wasn’t six yet and I had nothing left to do. I couldn’t even busy myself by making a start on dinner, because Mike was going to order in that takeaway. See, I told myself, that’s why I don’t want a break. I’m bored. I have nothing to do all day now that the kids have left home. What else can I do if I don’t have kids in?

This was key. As a specialist carer, one of the conditions of my employment was that I didn’t take any other job. I was required to be on call 24/7, as most of the kids we got in were so challenging, and needed such a lot of one-to-one support. Which was what I loved. Prior to fostering I’d been a behaviour manager in a large comprehensive school, looking after all the difficult and troubled kids. And it had been the idea of this demanding one-on-one role that had inspired me to do our kind of fostering in the first place.