По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

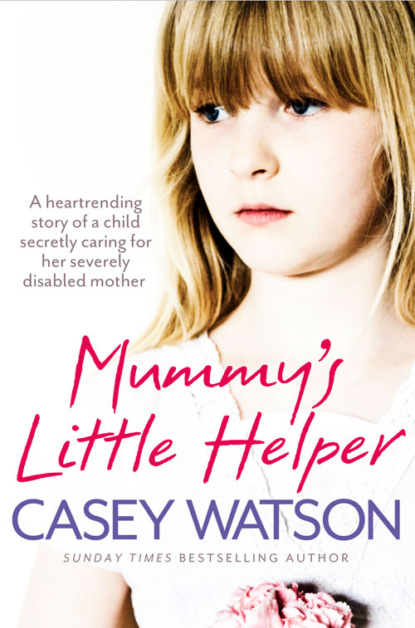

Mummy’s Little Helper: The heartrending true story of a young girl secretly caring for her severely disabled mother

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Because I really think we need to bring her now.’

‘Ri-ight …’ I said again, waiting for the next part of this process. The one where not only did we skip an initial meeting, but also skipped the first ‘get to know you a little’ visit, which was included to be sure both parties felt happy to proceed. I was fairly confident about this because by now I knew John well.

And he didn’t let me down. ‘We were kind of hoping you’d agree to take her on right away. If you’re amenable, that is …’ he finished apologetically. ‘Are you? I know it’s a lot to ask.’

I smiled to myself, loving how John always observed all the little protocols, bless him. Because when you thought about it, it wasn’t a lot to ask, really, was it? It was the job we did and I couldn’t think of a single prior occasion when ‘the process’, as written in the foster carer’s bible, had ever actually happened by the book.

And who cared? Doing things by the book was boring anyway. ‘Of course we are,’ I reassured him. ‘Well, I am, at any rate, and so will Mike be, I’m sure, just as soon as I call and tell him. He’ll be glad, to be honest, because it’ll give me something else to think about besides all the home improvements he’s terrified I’m going to schedule for our already perfect house.’

John laughed. ‘So I’ve actually done him a favour then, have I? Okay, so, let me see … okay if we pitch up in something like an hour and a bit?’

I told him yes, and immediately mentally switched gears. Outside the sun was slinking away from overseeing another grey February day. But suddenly I couldn’t care less. I disconnected and immediately reconnected – this time to Mike. I couldn’t wait for him to get home. Our New Year had begun.

Chapter 2 (#ufa41eb4c-5d98-5c52-909f-581fdc2a7e00)

Mike was home just in time for us to belt to the local supermarket and stock up with a few supplies before John arrived with our new house guest. On a bit of a New Year health kick, I had little in the way of treats in, and the couple of Christmas biscuits I’d had left in the tin had been hoovered up by Jackson and Riley the day before. It would be a bit of a mad rush, but I was determined to get it done, as I had no idea how things would pan out when Abigail arrived, and wanted to be able to concentrate all my energies on her. On the way I briefed Mike about what I already knew.

‘What a dreadful situation,’ he said as we parked the car. ‘Really makes you count your blessings, doesn’t it?’ I nodded. ‘But, at the same time, it couldn’t be better timing for us, could it? Sounds like she’s going to be the opposite of Spencer, at least, bless him.’

He was certainly right there. Our last foster child, to use the parlance, had run us ragged. So much so that I think we’d both been holding our breath when we’d been given the all clear two weeks back. Up till then we’d been on standby and unable to take another child, just in case his new situation – back with Mum and Auntie, but not Dad – proved to be unworkable for keeps. He had become so dear to us, and I was looking forward to hearing how he was getting on, but there was no doubt a part of me was warming to the idea of having the novelty (which it would be) of a quiet and well-behaved little girl taking his place. A distressed and anxious one, clearly – and no wonder, given her circumstances – but one with a completely different set of challenges to be overcome.

I grabbed a basket and tried to compile a list in my head of the sort of goodies I thought Abigail might like, getting Mike – six foot three to my own five foot nothing – to reach the items I couldn’t. Things didn’t normally involve so much guesswork, of course. The usual procedure, as well as those all-important meetings we weren’t having, involved the child filling in a short questionnaire we’d devised, in which they could tell us about all their likes and dislikes. It was just one of the ways we could help them feel settled at what was inevitably a stressful and unhappy time in their lives. With everything new and different it could be a comfort for a child to have some constants still in place – be it a favourite snack or special meal, or a much-loved TV programme not missed; such details could make all the difference to a child in distress.

With Abigail, however, we were going in blind, so I just used my judgement to throw in what occurred to me, while Mike lugged the increasingly heavy basket. ‘And at least we have some girl’s toys tucked away,’ I said, remembering our last little girl, Olivia, who’d come to us from a home of appalling neglect, and owned nothing bar one filthy, balding doll. I’d had something of a field day down at the charity shops for Olivia, and still had a good supply of soft toys and doll’s clothes, even if at nine Abigail might be too old for the enormous plastic play kitchen which had been my best-ever find to date.

Mike frowned, though. ‘I imagine playing’s going to be the last thing on her mind, love,’ he pointed out. ‘For the moment, at least. Poor kid. She must be reeling.’

He was right, of course. This was a uniquely sad and strange scenario – and for all of us. One step at a time. We quickly paid and hurried home.

We’d just finished putting things away and boiling the kettle when John’s car pulled up outside. I loved that this new house gave me a window onto the world. My kitchen was at the front of the house this time, and as it was where I spent most of my time it enabled me to indulge in my secret desire to be a ‘nosey neighbour’. I also liked the fact that we only had a small front garden. One, better still, that was covered with pebbles, so I wouldn’t have to spend much time on maintenance. The other positive was that just across the small road beyond our garden there was a nice grassy area with a children’s play section. That was enough to quell any guilt I had about my small but beautifully kept courtyard; that and the fact that we had a rather large back garden that I intended to fill with child-friendly play things for both the grandchildren and the children we’d be fostering.

Abigail looked dwarfed as she walked up the path in between John and her social worker. Still in her green-and-black school uniform, she stole a quick glance at me and Mike as we opened the front door. She was a pretty little girl, slim and petite, with her long fair hair held in two bunches which were neatly tied with matching green ribbon.

She also looked terrified. I was used to greeting children in distress, of course. There can be few things more bewildering and disorientating for a child than being made to go and live with complete strangers. But most children who came into foster care did so in carefully managed stages, so that even if the process was, by its nature, a relatively quick one, by the time it came to actually being deposited with their temporary family, the child had at least been there for a visit.

Poor Abby had had no such preparation. In less than a day her whole life had imploded. She’d gone to school this morning fully expecting to go home again and instead, she’d been picked up and told her mother was ill in hospital and that tonight she would have to sleep somewhere else. I was used to dealing with kids from bad family situations, but it still seemed inexplicable to me that this sweet little girl didn’t have a single other place she could go to. When my own two were her age it would have been unthinkable. Riley had her little gang of sleepover mates, most of whose mums were friends of mine too. All would have stepped in during a crisis like this one, just as I’d have stepped in had it been them.

My thoughts also naturally went to my Kieron, and how he would have fared in such a crisis. He was all grown up now – twenty-two – but he had Asperger’s Syndrome, a mild type of autism. He functioned well, had been to college and was doing well in life, but a change – any change – to his routine really stressed him. For someone like him, such a thing would be a major trauma. I’d thanked God many times for my network of friends and family, who knew his needs and idiosyncrasies and so could always help de-stress him. How would I have ever coped without them over the years?

Yet for this poor little girl there was no one. The social worker had already questioned both Abby and her mum about this, thinking, quite rightly, that if no family could be found at short notice, then a sleepover with a close pal would be the very next best thing. But no, it seemed the child didn’t have anywhere else to go. Unbelievable. And what on earth must have been going through her mind, knowing not only that complete strangers were rearranging her whole future, but that she had to go and live with some, too? I could only hope that the enormity of what might happen long term hadn’t yet impinged on her consciousness. As far as I was concerned, the best way to manage her in the short term would be to focus very much on the here and now.

I smiled my broadest smile as she hesitantly stepped into the hallway. Both her hands gripped the straps of the backpack she was carrying, and so tightly that the knuckles were white. I smiled as I recognised the logo on the backpack: ‘Glee’, accompanied by the all-singing, all-dancing cast publicity photo. Straight away I was thinking that if Abby liked all the latest stage-school TV programmes and paraphernalia, she would get along famously with Lauren. Lauren was Kieron’s girlfriend and was at performing arts college, and was used to me roping her in to help out with similarly minded foster children.

I also recognised the primary-school logo on Abby’s sweatshirt. Stanholme Primary, although the furthest away, was one of the better schools in the area, and also a feeder school for the big comprehensive I used to work at, and I’d known a couple of the teachers there. It was good to have a pre-existing connection with the place. It gave me a head start in that direction, at least.

‘Here she is. Here’s Abigail!’ John said, with a slightly forced brightness – he looked as worn out as he’d sounded on the phone. I ushered the trio into the dining room and Mike took their orders for hot drinks. Not that he had to go far to make them; like our last house, this too had an open-plan kitchen/dining set-up, the only difference being that the two were separated by a huge arch. Perfect, once again, for keeping an eye on kids.

Right now, of course, I had my eyes on Abigail. She’d hardly spoken – only mumbled an affirmative to a hot chocolate – and looked completely at sea, as if she might burst into tears or make a run for it at any moment. Again, this felt so different from what we’d seen before. We might be strangers – as might be John – but all our previous children had come to us with at least some sort of relationship, however slight, with the social worker assigned to them. As a result they usually clung to them, both physically and emotionally. But that was definitely not the case here.

Bridget Conley, a tall woman in her early forties, I guessed, filed in behind John. She looked nice enough, if a little detached, but it was so immediately obvious she and Abigail had barely met. It would have been so even if I hadn’t already known that. No one’s fault – all this had happened in less than a day, after all – though I couldn’t help feeling it a pity that they hadn’t managed to make some sort of connection. Bridget (whose face was vaguely familiar to me, nothing more) looked friendly and personable, but also as if she’d come from the sort of high-level meeting that she’d felt the need to power-dress for that morning. Where social workers normally dressed to suit the work they did – in comfortable, non-threatening, relaxed clothes, in my experience – Bridget looked more like a head teacher or a politician: all sharp angles, crisp creases and clacky shoes.

And I’d been right. ‘Apologies,’ she began as she started fishing in a laptop bag. ‘I’m not at all up on the paperwork, I’m afraid.’ She grimaced. ‘Been attending a case conference with my manager and her boss. Hence the suit and heels, I’m afraid.’ She grinned, somewhat sheepishly. ‘Why on earth do these things always get me so flustered? You’d think with twenty years in the job I’d be a little less bothered about dressing up for the upper echelons, wouldn’t you?’ She laughed then, and I found myself warming to her. A woman very much like myself, I thought.

John, too, was pulling the inevitable manila file from his briefcase, with such scant notes as he’d presumably been so far able to make. And looking at the tableau of officialdom in front of me made me have something of a ‘eureka!’ moment. While Mike clattered with cups and teaspoons, I looked straight at John. ‘I tell you what,’ I said to him. ‘How about you all take a breather for a moment and enjoy a cup of tea. Been quite a long and stressful day, eh?’ I said, turning my gaze now to Abigail. ‘And why don’t you and I take a look round my beautiful new garden? We’ve only just moved in here, and I’m so excited about it. And it’ll be dark soon …’ I held out my hand.

My hunch had been right. No sooner had Abigail seen it than she’d grabbed hold of it gratefully and, finally being persuaded to take off the backpack, she let me lead her from the room. It was if she’d been drowning and was desperate for a life-belt to cling on to; an escape from the turbulent waters of this surreal situation that she had suddenly, inexplicably found herself in.

I led her through the living room and pulled open the French doors that looked out onto the garden. ‘How about that, then?’ I asked her.

I watched her gaze go exactly where I’d imagined it would – to the enormous trampoline in the far corner. It had been something we’d inherited – literally – as we’d been told the previous tenants, who’d gone abroad, had had no time to dismantle it and sell it. So they’d simply left it for whoever moved into the house next, much to Levi and Jackson’s delight. ‘It’s a big one, isn’t it?’ I added, smiling down at Abby now.

She dutifully smiled back and stepped outside with me into the garden. ‘You know, I have two little grandsons, Abigail. There’s Levi, who’s three, and baby Jackson, who’s nearly one. If you like, when they come to play you could show them how to bounce on it.’

Abigail, who was still clutching my hand, looked thoughtful. ‘Yes, I’d like that,’ she said, sounding almost painfully solemn. ‘But Mrs Watson? I think you need to put a net around it first. I’ve seen them on TV and you need those for very little people.’

Bless her, I thought, touched by her serious tone. ‘You know what?’ I said. ‘You’re right. And I never thought about that, love. I’ll have to mention it to Mike, won’t I? Good point. By the way, do you prefer to be called Abigail or Abby?’

Again, she seemed to need to think carefully before answering. ‘Well, my mummy calls me Abby, so I think I’d prefer that. Though my teachers call me Abigail, so I don’t suppose it matters. Whichever you want, really.’

She looked up at me, managed to find another half-smile from somewhere. ‘No contest, then,’ I said. ‘Abby it is.’

She didn’t seem to know what to do or say then, and seemed content to let me lead her on a short tour of the garden, while I did the bulk of the talking. Now clearly wasn’t the time to expect her to open up to me. She’d probably been bombarded with questions from the minute she’d been fetched from school and taken to the hospital. And I didn’t doubt her mind was very much still back there, with her poor mum. My heart went out to her. She must have felt as if she’d been abducted by aliens, which, in a practical sense, she sort of had. What I imagined she most needed was a distraction from the clamour of her fearful thoughts. ‘So,’ I told her, ‘I’m called Casey, okay? No “Mrs Watson”. And Mike, that great big man you just met in there? Well, he’s my husband. And what we do is look after children who, for whatever reason, can’t stay in their own homes for a bit. Did John explain all that to you? Why you’re here?’

Abigail nodded. It was growing dark now and I led us across to the bench seat on the patio. It was cold, but not wet, as it was partly sheltered by a fibre-glass lean-to. It was the only disappointment; a poor second to the wonderful conservatory we’d had in the last house. But it was functional, at least. And also temporary. Mike didn’t know it, but I fully intended to wait a few months, and then badger him mercilessly about getting us a new one. I patted the space beside me on the bench, and she obediently sat down, finally letting go of my hand.

‘So that’s what we’re going to do,’ I went on. ‘Take care of you. So you mustn’t worry about anything, okay? And the first thing we’re going to do is get things sorted so we can get you back to visit your mum as soon as possible –’

‘Tonight?’ she asked timidly. ‘I really need to make sure she’s okay.’

I shook my head. ‘Not tonight, I don’t think,’ I said gently. ‘But definitely this week. If not tomorrow, the next day. After school. We’ll make sure of that, don’t worry. We’ll fix it up with John and Bridget, before they go. And Mummy’ll be fine, you know. She’s in a safe place, and they’ll take really good care of her, just like we’re going to take really good care of you. Now then, how about that hot chocolate and a biscuit? They’ll be wondering where we’ve got to out here, won’t they? Hmm?’

I turned now, to look at her properly. The outside light had already picked out a shiny trail on her face, which marked where tears were slipping silently down her cheeks. The instinctive thing to do, as had been the case with holding out a hand to her, was to pull her towards me and hug her. It was as natural to me as breathing, as it would be to anyone. But with kids in care – particularly the long-term emotionally damaged kids we mostly dealt with – often that’s the last thing they need or want. Starved of normal human relationships, or, sometimes, all too familiar with dangerously inappropriate ones, they can find it almost impossible to empathise or be physical with the very people who most want to help them. But this was not that; this was a normal and clearly much-cherished little girl, who wanted nothing more keenly to be back with the mum who loved her. I scooped her into my arms and she sobbed hard against my chest, and as she did so I reflected that some good might come of this. Fingers crossed, they would soon sort out something workable for her mum’s care and, that done, she’d be able to enjoy at least some semblance of normality for what still remained of her childhood.

I had no reason to expect things to be otherwise at that point. Silly me. Is life ever that simple?

Chapter 3 (#ufa41eb4c-5d98-5c52-909f-581fdc2a7e00)

Abby seemed much better for a cry and a cuddle, and when we returned to the dining room she had got herself composed again, and settled down to a biscuit and her by now lukewarm hot chocolate, which she wouldn’t let Mike pop into the microwave for her. ‘It’s safer to drink it like this, anyway,’ she said quietly, before wrapping both her hands around the mug.

‘So,’ said John, once he’d confirmed details of the hospital visit and reassured Abby that she’d soon be able to see her mum again. ‘I think we’re about done here. And I expect this little lady needs to get to bed, eh?’ He looked at Abby, who was staring into her now empty mug as if it might hold the answer to how she had come to be here. She looked up at him, as if the word ‘bed’ was physically painful. All she wanted, I felt sure, was her own bed.

Mike and I exchanged glances while Bridget said her goodbyes. The mood was sombre now, Bridget having outlined, albeit in the gentlest of tones, that for the moment, at least, Abby would only be able to visit her mum a couple of times a week. Though I understood why – daily visits would be both impractical (the hospital was some distance away) and could potentially slow down the process of adjustment – I really felt for her. This was the mum she had seen every single day for her entire life. No wonder she looked so distraught.

And to really hammer home the drastic and abrupt nature of this disaster, here she was, being deposited with us – a pair of strangers. We were used to this, of course – this business of children who hardly knew us being delivered to our doorstep – but we really were strangers to Abby. No preliminary visits, no chance to get used to the idea; I kept reminding myself that she’d first clapped eyes on us less than an hour ago. I also tried to keep in mind that in the Second World War this was something that hundreds of thousands of kids had gone through, my own and Mike’s parents included. But that was a lifetime away, and knowing it would be of absolutely no comfort to this traumatised child. I stood up again and went round to her side of the table. ‘I thought we might have a little sit-down together before bed,’ I said, placing my hands on her shoulders and dipping my head close to hers. ‘Once we’ve shown you your bedroom and you’ve unpacked and we’ve had our tea, of course. And a rummage through my special bits and bobs box, as well. I had this idea. I thought it might be an idea to get a bit of a diary started. Even a scrapbook, perhaps, that we can stick pictures and special things into. So you can keep mummy up to date with what you get up to while you’re here. Would that be an idea? I bet she’d like that, don’t you?’

I could once more see the white of Abby’s knuckles as she held on to the mug. She was close to tears again, I noticed, now John and Bridget were leaving. For all that there hadn’t been time for them to forge a bond yet, Bridget’s was obviously still the most familiar face in the room.

And Bridget could clearly see that herself. She wasn’t stupid; she knew that to gush at Abby now would create a chink in her fragile composure. Like every social worker, I imagined she’d had her fair share of situations where a desperate child had clung on to her for grim death. ‘Splendid!’ she declared briskly, as she shrugged on her jacket and slid her slim sheaf of papers back into their slip-case. ‘And when I’m back –’ She glanced at me now. ‘Which will be in – let me see now … two weeks – you can show me all the things you’ve been up to with Mike and Casey, hmm? All the adventures you’ve been having with them. Yes?’