По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

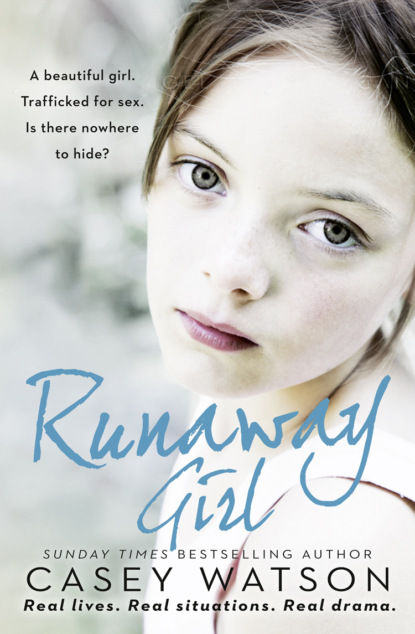

Runaway Girl: A beautiful girl. Trafficked for sex. Is there nowhere to hide?

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Well, they do in some cases …’ I said. ‘Depends very much on the circumstances. But in this case, of course not. They first need to establish what she might be going back to. We don’t yet know how she got here – even how long she’s been here, come to that. Why, anyway?’ I asked, curious.

‘Oh, it’s just there’s this idiot at football I train with,’ he said. ‘He’s a complete racist.’ He glanced at Lauren. She obviously knew about this character already.

‘Amongst other things …’ she added. ‘All-round nice guy, isn’t he? We hear a lot about Idiot Ben,’ she explained, smiling at me.

Kieron huffed. ‘Because he is an idiot,’ he said, shrugging the jacket off. ‘Anyway, he was telling me they changed the laws so no one can come here any more.’

‘I’m not sure he’s right about that,’ Mike commented, putting his own on. ‘Though there’s a fair few who’d agree with him, if they had.’

‘But why?’ Kieron seemed genuinely to want an explanation. ‘I don’t get it. We all live in Europe. We’re all humans on the planet. And, anyway, no one stops us going to work there.’

‘I’m not sure working there’s the issue,’ Mike said.

‘Yes it is,’ Kieron said. ‘He’s always banging on about how they take all our jobs.’

‘When he’s not banging on about them taking our benefits,’ Lauren added drily.

‘Except do they?’ Kieron asked. ‘And they can’t do both, can they?’

Mike touched his arm. ‘I’m with you there, son. Though I think that’s a discussion for another day, don’t you? We’ve got to get a move on or your mum’ll start getting ants in her pants. There’ll be at least a dozen specks of dust lurking that she’ll have to send packing …’

‘Huh,’ Kieron said. ‘I flipping knew I was right. I really hate it when people assume I don’t know anything about anything.’

‘Which he will doubtless be addressing at the next football training session …’ I whispered to Mike as we hurried out of the door.

We returned home to find Tyler exactly where we’d left him – engrossed in the latest episode of CSI: NY, which was his latest ‘must-see’ TV show. And no sooner had we filled him in on our imminent young visitor than my mobile rang again, to alert us that the girl was now with John, and that, assuming we were okay with it, he’d be round with her in half an hour.

‘It’s a point, you know,’ Mike said, once I’d delegated jobs, and sent Tyler off to the kitchen to do his washing up and generally straighten things up downstairs. ‘You know, about her status here. Will she really be allowed to stay? What’ll they do with her if she’s got nobody and doesn’t speak any English?’

‘I have absolutely no idea,’ I said. ‘This is a new one on me, although I’m sure John knows the protocols. But I suppose at the moment, like we were saying, it’s a case of a roof over her head, bless her. I wonder what her story is. I mean, how did she find her way here? She’s a hell of a long way from home.’

My instinct was that that her being Polish would make no difference in the short term. There were generally two options with young people found on the street: the police would either take them home again or, if this was neither possible nor appropriate, call in social services to take over from there. In other cases, kids who’d run away to escape abuse became so exhausted and traumatised from not eating and not sleeping (or, worse, being beaten up or raped) that they’d take themselves to social services, pleased to be taken into care. It sounded like our young runaway fitted into the latter category, bless her.

‘She’s probably been trafficked,’ decided Tyler, once he’d whizzed through his chores and come and joined us.

Mike chuckled as he went in search of bedding across the landing. ‘And you’d know all about that, I suppose.’

‘No, honest. I bet she has. They sneak them in through the Channel Tunnel under lorries. I saw a thing about it on telly the other week. What’s she like, anyway? What’s John said about her?’

‘Almost nothing, love,’ I told him. ‘And no interrogations, okay? We’re not in an episode of CSI: NY, remember. ‘Here,’ I added. ‘Strip that duvet cover off for me, will you? I doubt Frozen is really going to be her thing. Mind you, I’m so out of touch these days with teenage girls that I’m not sure what her thing might actually be.’

‘Well, I haven’t done much better,’ Mike called from his foray into the airing cupboard – an airing cupboard somewhat depleted as the result of one of my periodic New Year clear-outs, in preparation for a big shop in the January sales. Which I’d not quite got round to.

‘It’s basically a choice between Newcastle United and The Little Mermaid, currently,’ Mike said, brandishing both sets in the bedroom doorway. ‘Unless we put her in the double in the other spare room, but of course that means clearing all the junk out of it, of which there is a lot …’

I stuck my tongue out at him, refusing to feel guilty about what I had managed to accomplish, which had been an overhaul and restock of my ever-expanding collection of toys. ‘No, no time,’ I said. ‘The Little Mermaid will have to do for now, I guess. Though I’m sure we had a simpler one. One with butterflies on. Oh God, surely all girls like mermaids?’

‘That’s sexist stereotyping, that is,’ Tyler quipped. ‘We just did it in PSE class. How d’you know she’s not, like, a massive Newcastle fan?’

‘That’s a fair point,’ I conceded. ‘Though I suspect it might be wishful thinking on your part. Here. Grab the other end of that duvet – oh, but, God, that’s a thought!’

‘That sounds ominous,’ Mike said. ‘Go on then. What’s a thought?’

‘Polish! We don’t know any, do we! How are we going to greet her? I’m going to have to go down and fire up the laptop before she arrives.’

‘I do,’ said Tyler. ‘We’ve got those two Polish kids in my class, haven’t I? Hang no – Mum, you’ve even met one. You know – Vladimir? Sooooo … What do I know … Erm … Okay, here’s one. “Ziom”.’

‘Come again?’ said Mike.

‘Ziom. It means bro,’ explained Tyler. ‘You know, like in “bruvva”. As in, like, when you meet someone and you fist bump, and say, “Hey, bro – how’s it hanging?”’ He did a little fist bump with Mike to illustrate.

‘Well, that’s extremely helpful, I don’t think,’ I told him. ‘I need “welcome” and “come in” and “This is your lovely temporary bedroom, but please don’t read anything into The Little Mermaid duvet cover”.’

I threw the last Ariel-emblazoned, half-in-its-case pillow at him. We needed all of that, yes, but mostly ‘Don’t be scared, love, you’re safe now’. I left the bedroom and hurried down the stairs, suddenly remembering that Tyler would have probably left me a sinkful of dirty dishes and mugs to sort out as he’d been home alone for a couple of hours.

Chapter 2 (#ua7934ea9-96e6-5d32-ac14-80624485034c)

The first thing I noticed about Adrianna was her hair. There was so much of it that it would have been impossible not to notice it: thick and wavy, it was the colour of a church pew or polished table and, though it was clearly in need of a good wash and brush, it was the sort of hair my mum would have called her ‘crowning glory’. And it was long, falling down to her waist.

She was tall too – as girls often are at that age. A lot taller than I was – which wasn’t hard, admittedly. She was also painfully skinny, but though she looked exhausted and in need of a good meal, there was no denying her natural beauty.

‘Come in, come in,’ I urged, gesturing with my hand that she should do so, trying to reassure her, despite knowing that there was little I could say – in any language – that would make her less terrified than she so obviously was. Not yet, anyway. I knew she was a child still but I doubted there was a person of any age who’d find anything about her current situation easy.

In common with so many of the children Mike and I took in, Adrianna had arrived with barely anything. She had a small and obviously very old leather handbag, the strap for which she held protectively, like a shield. Other than the bag – and it could have barely housed more than a purse and passport – she appeared only to have the clothes she stood up in. A pair of sturdy boots – again, elderly – and of a Doc Martens persuasion, a long corduroy skirt in a deep berry shade, a roll-neck black jumper and a leather biker jacket, which, once again, had clearly seen better days.

And all of it just that little bit too big for her. So, on the face of it she should have looked like the refugee she purported to be, but instead she had the bearing and grace of a model. It was only her eyes that betrayed her anxiety and desperation. I found myself wondering two things – first, when she might have last had a bath or a shower, and second, what kind of background she had come from. Bedraggled as she was, I knew that those boots and that jacket wouldn’t have been cheap.

‘So,’ said John, herding her in but never quite making contact – I sensed a strong reluctance on his part to try to baby her too much. ‘No luck with an interpreter, so we’re just going to have to make the best of it tonight, I’m afraid. I’ve left a message with head office and made it clear that it’s urgent, so hopefully we’ll have better luck getting hold of someone tomorrow morning. In the meantime –’

‘In the meantime, you look frozen,’ I said to Adrianna, grabbing her free hand impulsively and seeing the fear widen her eyes. I let her go again, smiling, trying to keep reassuring her. ‘Look at you,’ I said again, now rubbing my hands up and down my own arms. ‘A hot drink, I think. Coffee? Kawa? Tea?’

‘Kawa, dzieki. Dzieki,’ she answered.

‘Thank you,’ said Tyler, who was standing with Mike behind me. ‘Dzieki means thank you,’ he explained, smiling shyly. And he was rewarded by the ghost of a smile in return.

I took her hand again and this time I grasped it more firmly. ‘You’re welcome,’ I said, squeezing it to underline my words.

‘Dzieki,’ she said again, her eyes glinting with tears now. ‘Dzieki. Dzieki. Dzieki.’

In the event, there was no need for an extended session of complicated, halting, hand-gesture conversation because all Adrianna wanted to do was go to bed. Once she’d gulped down her coffee – and she really did gulp it – she almost bit my hand off when I gestured we might go upstairs.

And I understood that. I had no idea how far she’d travelled or what sort of trauma she’d run away from, but the need to shut the world out is a universal one.

‘So, this is the bathroom,’ I explained needlessly once we’d arrived on the landing, leaving Mike and John downstairs to deal with the paperwork. Tyler, too, seemed to understand he’d be better off leaving us to it. Having exhausted the little stock of useful Polish that he knew, he’d quickly announced he was off to spend some time on Google Translate and disappeared into his own bedroom.

‘Make yourself at home,’ I said to Adrianna, gesturing again, this time towards the bottles of shower gel and shampoo. ‘Have a bath, if you want. I’ve sorted out some clean nightclothes and put them on your bed …’

To which the same response came – dzieki, dzieki. She didn’t seem to want to attempt to say anything else.