По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

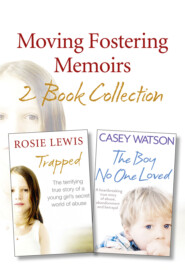

Angels in Our Hearts: A moving collection of true fostering stories

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Charlie has been on the vulnerable children’s register since birth, as his mother, Tracy, has struggled for years with depression and addiction issues. With support, Tracy has demonstrated that she’s able to meet Charlie’s basic needs, but he’s rarely present at nursery, and neighbours have complained of continued bouts of crying coming from their flat. Tracy has no extended family or network of friends to offer support.

Late this evening Charlie was found wandering the concrete walkway below the family home. Though his vocabulary seems limited, the boy indicated to a passer-by that he had fallen from the first-floor window. Police were unable to rouse his mother when they entered the flat. She appeared to be heavily intoxicated. Charlie’s currently in A&E where he’s receiving treatment for a gash to the head. An urgent foster placement is required while investigations are carried out.

I click ‘X’ to close the window, and sit staring at the blank screen for a moment. It sounds to me like both Charlie and his mother have been living an isolated existence, with no one but professionals around to offer support. My stomach begins to churn, as it does whenever someone new is about to arrive.

Stop fretting, I tell myself. If Des were here he would say, ‘You’s haven’t done too badly so far, m’darling.’ All of the children I’ve cared for in my years as a foster carer have left happier than when they came, so I suppose he’d be right. Knowing the trauma Charlie has been through, I feel the familiar tug to offer comfort intensifying. The chance comes sooner than expected. Just as I’m finishing the dregs of my coffee, the doorbell rings.

Charlie stands on the doorstep, the top of his mousy-coloured hair bathed in pale moonlight. The delicate skin above his right eye is covered with white gauze and tape, held in place by a bandage circling his head like a bandana. I can’t see his face as he’s staring down at his black plimsolls, but I notice how tiny he looks next to the stocky police officer beside him. It’s freezing, but all he’s wearing is a pair of dirty pyjamas. A middle-aged woman, presumably the duty social worker, hovers behind.

‘I’m Evelyn,’ she says, leaning around the officer who’s massaging Charlie’s shoulder with meaty fingers.

‘Hello, Evelyn. And you must be Charlie,’ I say softly, crouching down to his level.

His eyes are barely visible under a heavy crop of wispy hair, but I can sense bewilderment there. His features are small and appealing but unusually angular for a child so young – he’s much too thin. His head hangs awkwardly to one side, as if it’s too heavy or uncomfortable to hold up. I feel a rush of pity.

‘You look freezing. Come in, all of you.’

‘He wouldn’t let me carry him or wrap him in my coat,’ Evelyn says, as she follows me through the hall, her fingers on Charlie’s back, propelling him in. His eyes are swollen with tiredness. ‘And we couldn’t find anything warm for him at the flat.’

She hands me a small, grubby Fireman Sam rucksack. ‘Here are a few of his bits, but not much, I’m afraid.’

When we reach the living room she leans towards me. ‘Most of his clothes were damp, covered in all sorts. Mum was so out of it we couldn’t make head or tail of what she was saying.’

‘It’s OK,’ I say. ‘I have spares.’

Turning to Charlie, I kneel beside him. He stares at me with an anxious frown.

‘Don’t worry, Charlie, everything will be fine. We’ll find you some things to wear in the morning. I’m Rosie, by the way. You’ll be staying with me for a bit. You’re safe here, sweetie.’

The police officer, a man in his forties with closely cropped dark hair, smiles warmly at me, then grimaces and shakes his head, his expression saying: doesn’t bear thinking about, does it?

Evelyn and the officer sit on the sofa, and Charlie sinks down on the rug in the middle of the floor, exhausted.

‘I know the mum.’ The social worker speaks out of the corner of her mouth like a ventriloquist, as if Charlie would be unable to hear that way. ‘I was hoping she’d get a grip on things, but …’ She gives a weary sigh, shrugging her shoulders. ‘Well, you know …’

I nod. How many times had I seen it now? An over-dependence on alcohol or drugs – or both – and a child’s chances of having a good day or a harrowing one spin on a penny, all determined by the chemicals pulsing through their mother’s veins. It’s not always beatings and bruises that signal the end of a birth family and the beginning of life in foster care, I muse. Sometimes it’s a simple case of daily deterioration, the slow unravelling of a mother’s ability to cope. I flick my mind back to the early days, after my daughter Emily was born.

Catapulted into a life without the reassuring structure of work, I felt isolated and lonely. Each day was seemingly endless, and the monotonous cycle of changing, feeding and rocking really got me down. If someone had told me back then that I would soon choose to spend my life caring for other people’s children, I would have pronounced them deluded. Remembering how lost I felt, it doesn’t take a huge stretch of the imagination to think that I too might have been unable to cope, perhaps drifting towards a crutch to numb the feelings of uselessness. I shudder at the thought, feeling a stab of pity for both mother and child.

Charlie’s chin is quivering. I’m not sure whether it’s with cold, fear or perhaps because his head’s aching.

‘When did he last have pain relief?’ I ask Evelyn, while I reach behind the sofa for a small, pale-blue blanket. I drape it around his shoulders then sit quietly beside him, letting him get used to having me near. He looks sideways at me with solemn eyes and I smile, noticing that his face is dotted with fine white crusts, presumably salty deposits from anxious tears at separating from Mum.

‘Just before we left the hospital, about …’ Evelyn inclines her head towards the police officer.

He checks his watch, pursing his lips. ‘About half an hour or so ago, I’d say.’

I nod grimly, knowing that the poor little mite is in for a rough few days. With his legs splayed and shoulders hunched over, Charlie looks like he’s reached the same conclusion, as if he’s lost all hope at the tender age of three. Watching as he nibbles his fingernails, tearing into the ragged skin, I’m flooded with a longing to pick him up and soothe him.

It’s actually this first, unscripted half an hour or so that I find the most difficult, when I’m weighing up what the child needs, trying to read their signals. I’m getting better at it. In the early days I was overly attentive, moving awkwardly around children who probably would have preferred a little distance while they adapted to their new environment. I would fuss around, straightening toy boxes that were doing perfectly well where they were, and offering endless litres of juice and other refreshments. Experience has taught me to hold back a little.

Evelyn hands me a short report from the hospital to read. I’m pleased she’s decided not to discuss everything in front of Charlie, especially once I read the contents. It seems that his short life has been peppered with regular trips to the emergency department – scalding-hot tea spilt on him when he was just three months old, stitches at the age of nine months after a falling shelf happened to catch him on the head. The depressing list goes on and suddenly Charlie’s mother becomes a more shadowy figure. My sympathy wanes.

It’s a familiar tale. Another early childhood eroded by circumstances, leaving the vulnerable – well, Charlie at least – lost, scared and sitting alone in a heap on my rug. It will take a while for the fragments of his short life to be pieced together. With an investigation underway, nursery teachers, GPs, health visitors, everyone who has come into contact with Charlie will be interviewed and the jigsaw will eventually be pieced together. Of course, there will be gaps, ones that perhaps only his mother will ever be able to fill. The emerging picture will hopefully reveal neglect and not wilful abuse; I still struggle to come to terms with the possibility that a mother could deliberately harm her own child. However many times I hear about it, my brain just can’t assimilate something that disturbing.

The rest of the hospital report matches what was summarised in Des’s email and, for now, what more do I need to know? Evelyn hands me a leaflet – Care Following a Head Injury – reminding me of my own duty of care. Every parent knows how heavily the responsibility of caring for a child can sometimes weigh, especially when they’re unwell. That responsibility increases tenfold when that child is a ward of the state. For a brief moment I feel overwhelmed, but then I remind myself that help is just a phone call away, should Charlie take a turn for the worse.

‘They’ve assured us that there’s no sign of serious injury,’ Evelyn says, perhaps noticing the cloud passing over my face, ‘but best keep a close eye on him. It seems he had a soft landing so they don’t think he bumped his head. From what the neighbours had to say, he cut his head on the lid of a tin can, but if there’s any vomiting or you’re at all concerned …’ She makes an L shape with her forefinger and thumb, raising her hand to her ear in imitation of a phone.

‘Don’t worry, I’ll stay close by.’

Evelyn hands me a placement agreement to sign and I scribble my signature, longing for her and the constable to leave so that I can get Charlie settled.

‘Well, we’ll leave you to it.’

Evelyn zips up her bag and rises to her feet. The movement rouses Charlie, who was beginning to nod off where he sat. His head shoots up and he howls, rocking back and forth in a self-soothing action. To see such a small boy surrounded by adults and yet too afraid to reach out to any of us for comfort almost makes me weep. He must think the world an unfriendly place and I wonder how he’ll cope with all the turmoil ahead. Children in care have to adjust to lots of different people coming and going in their lives.

‘Aw, it’s all right, sweetie,’ I whisper, reaching down to lift him up. His legs dangle lifelessly around my hips but he stops howling, tears rolling silently down his cheeks. He must have feared we were all about to abandon him.

‘I’m not going anywhere, honey. I’m going to take care of you.’

He nuzzles his face into my shoulder. I can feel heat from his little body pressing against my side. His bandaged head rests against my cheek, the sticky tape cold against my skin. With Charlie perched on my hip I walk quickly through the hall to show Evelyn and the officer to the door, wondering if Charlie’s path had been mapped out from the moment he was born. Could his mother, on the day she first cupped his tiny head in the palm of her hand, ever have imagined that barely three years later she would lose him, at least for the foreseeable future? The might of social services rides like a steam roller over families, whose fate sometimes turns on which social worker is assigned to work on their case.

On my way back to the living room I fall into the classic words of comfort – ‘There, there, it’s all right, you’re safe here, baby, no need to cry. Hush now, sweetie, everything’s going to be fine’ – but I suspect that Charlie’s in a place where words won’t reach him. With his face tear-streaked he glances up at me, his dirty, overlong fringe falling across his eyes. Close up he smells of hospitals, although antiseptic masks another, acrid stench: tobacco and something muskier.

‘Come on, sweetie. Let’s get you a drink and then we’ll tuck you up, shall we?’

I walk to the kitchen, chatting in soft, sing-song tones. As I pour the milk I notice him watching me with a sullen wariness. He really could do with a bath, but I won’t put him through the trauma at this time of night. What he needs, over and above anything else, is sleep. I hand him a beaker of milk and he takes it, listlessly running the sippy lid over his lips.

‘There’s a good boy. Have a nice drink.’

He begins to cry again and I feel a familiar sharp pang in my stomach, a longing to reassure him that what he’s known is not all that there is.

Ten minutes later, talking in a loud whisper so as not to wake the others, I hold his hand and guide him, still hiccoughing with tiny sobs, into the spare room.

‘I want Mummy!’ he wails suddenly, the sight of an unfamiliar bed filling his voice with urgency. He sinks to the floor, tears streaming down his puffy red cheeks.

Searching through the rucksack that Evelyn gave me, I try to find a comforter, something familiar that might smell of his mother and console him. Apart from a few ragged items of clothing there’s nothing; no teddy or special blanket. Reaching up to the top shelf of our bookcase, I grab the first teddy I lay my hands on. Lowering my chin to my chest, I deepen my voice and make teddy pretend-talk.

‘Hello, Charlie. I’m Harold. Can I come to bed with you?’

Charlie stops mid-sob, his eyebrows slowly rising with interest. Holding his breath, he stares at ‘Harold’ and nods, clasping the stuffed toy to his chest and wiping his tears on the soft fur. Gently steering him to bed, I half lift, half guide him in. He winces in pain as his head touches the pillow. The tears return as I switch off the main light and plug in a night lamp.

‘Night, night, Charlie,’ I whisper, sitting beside his bed and stroking his hair. Eventually his breathing settles and his eyes flutter to a close.

That night I stage a vigil beside his bed, setting my alarm at two-hourly intervals so that I can keep a regular eye on him. I am surprised to find that he sleeps through it all, and I even manage to get snatches of uninterrupted sleep myself between checks. I guess that he must have been too exhausted from all the drama to fret about his unfamiliar surroundings.

At 5 a.m. I am confident enough to leave him and chance an hour’s rest in my own bed. It’s Saturday morning and there aren’t any football matches or clubs to get the older children up for, although at just gone six o’clock I get up anyway to make sure Charlie’s not lying awake and fretting. Creeping along the hall, I peer around his bedroom door – he’s curled up on his side in a tight ball, one hand tucked between the pillow and his pink cheek, the other arm resting heavily on teddy. Soft dimples of flesh emerge from the cuffs of his over-small pyjamas, his tiny fingers lightly brushing against his chin. He looks angelic and, I’m relieved to find, quite relaxed.